Acute Gingival Infections and Their Clinical Features

Acute gingival infections such as Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis, Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis, and Pericoronitis are discussed in this content. Learn about the primary infection caused by herpes simplex virus type 1, its symptoms, secondary manifestations, and clinical features. Explore specific learning objectives and core areas related to these conditions.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

RUNGTA COLLEGE OF DENTAL SCIENCES AND RESEARCH,BHILAI ACUTE GINGIVAL INFECTIONS 1 DR PUSHPENDRA SINGH YADAV SR. LECTURE DEPT. OF PERIODONTOLOGY

SPECIFIC LEARNING OBJECTIVES CORE AREAS Introduction DOMAIN Affective CATEGOR Y Desire to know Cognitive Must to know Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis Cognitive Must to know Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis Cognitive Must to know Pericoronitis 2

CONTENTS PART-I Introduction Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis PART -II Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis Pericoronitis Summary References 3

PRIMARY HERPETIC GINGIVOSTOMATITIS an infection of the oral cavity caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1. It occurs most often among infants and children who are less than 6 years old, but it is also seen in adolescents and adults. It occurs with equal frequency in male and female patients. In most individuals, however, the primary infection is asymptomatic. 4

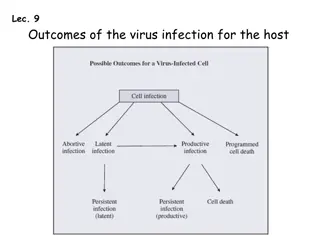

As part of the primary infection, the virus ascends through the sensory and autonomic nerves where it persists as latent HSV in neuronal ganglia that innervate the site. In approximately one-third of the world s population, secondary manifestations result from various stimuli, such as sunlight, trauma, fever, and stress. 5

These secondary manifestations include: herpes labialis herpetic stomatitis, herpes genitalis, ocular herpes, and herpetic encephalitis. Secondary herpetic stomatitis can occur on the palate, on the gingiva, or on the mucosa as a result of dental treatment that traumatizes or stimulates the latent virus in the ganglia that innervate the area; it may be present as pain away from the site of treatment 2 4 days later. Careful inspection for characteristic vesicles may be diagnostic 6

CLINICAL FEATURES ORAL SIGNS appears as a diffuse, erythematous, shiny involvement of the gingiva and the adjacent oral mucosa, with varying degrees of edema and gingival bleeding. During its initial stage, it is characterized by the presence of discrete, spherical gray vesicles, which may occur on the gingiva, the labial and buccal mucosae, the soft palate, the pharynx, the sublingual mucosa, and the tongue. 7

After approximately 24 h, the vesicles rupture and form painful small ulcers with red, elevated, halo-like margins and depressed yellowish or grayish-white central portions. These occur either in widely separated areas or in clusters where confluence occurs. 8

Occasionally, primary herpetic gingivitis may occur without overt vesiculation. The clinical picture consists of diffuse, erythematous, shiny discoloration and edematous enlargement of the gingivae with a tendency toward bleeding. The course of the disease is limited to 7 10 days. The diffuse gingival erythema and edema that appear early during the course of the disease persist for several days after the ulcerative lesions have healed. Scarring does not occur in the areas of healed ulcerations. 9

The disease is accompanied by generalized soreness of the oral cavity, which interferes with eating, drinking, and oral hygiene. The ruptured vesicles are the focal sites of pain; they are particularly sensitive to touch, thermal changes, foods such as condiments and fruit juices, and the action of coarse foods. In infants, the disease is marked by irritability and refusal to take food. Extraoral and systemic signs and symptoms Cervical adenitis, fever as high as 101 105 F (38 40.6 C), and generalized malaise are common. 10

HISTOPATHOLOGY The virus targets the epithelial cells, which show ballooning degeneration that consists of acantholysis, nuclear clearing, and nuclear enlargement. These cells are called Tzanck cells. Infected cells fuse to form multinucleated cells, and intercellular edema leads to the formation of intraepithelial vesicles that rupture and develop a secondary inflammatory response with a fibropurulent exudate Discrete ulcerations that result from the rupture of the vesicles have a central portion of acute inflammation, with varying degrees of purulent exudate surrounded by engorged blood vessels. 11

DIAGNOSIS It is critical to arrive at a diagnosis as early as possible in a patient with a primary herpetic infection. Treatment with antiviral medications can dramatically alter the course of the disease by reducing symptoms and potentially reducing recurrences. The diagnosis is usually established from the patient s history and the clinical findings. 12

Material may be obtained from the lesions and submitted to the laboratory for confirmatory tests, including virus culture and immunologic tests that involve the use of monoclonal antibodies or deoxyribonucleic acid hybridization techniques. This should not delay treatment if strong clinical evidence exists for primary gingivostomatitis. 13

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis should be differentiated from several conditions. Lesions of recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) range from occasionally small (0.5 1 cm in diameter), well-defined, round or ovoid shallow ulcers with a yellowish-gray central area surrounded by an erythematous halo, which heal in 7 10 days without scarring, to larger (1 3 cm in diameter) oval or irregular ulcers, which persist for weeks and heal with scarring. 14

The ulcerations may look the same for the two conditions, but diffuse erythematous involvement of the gingiva and acute toxic systemic symptoms do not occur with RAS. A history of previous episodes of painful mucosal ulcerations suggests RAS rather than primary HSV 15

COMMUNICABILITY Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis is contagious. Most adults have developed immunity to HSV as a result of infection during childhood, which, in most cases, is subclinical. For this reason, acute herpetic gingivostomatitis usually occurs in infants and children. Recurrent herpetic gingivostomatitis has been reported although it is not often clinically significant unless immunity is destroyed by debilitating systemic disease. 16

PERICORONITIS The term pericoronitis refers to inflammation of the gingiva in relation to the crown of an incompletely erupted tooth. It occurs most often in the mandibular third molar area. Pericoronitis may be acute, subacute, or chronic. 17

CLINICAL FEATURES The partially erupted or impacted mandibular third molar is the most common site of pericoronitis. The space between the crown of the tooth and the overlying gingival flap (operculum) is an ideal area for the accumulation of food debris and bacterial growth. Even in patients with no clinical signs or symptoms, the gingival flap is often chronically inflamed and infected, and it has varying degrees of ulceration along its inner surface. 18

Acute inflammatory involvement is a constant possibility; it may be exacerbated by trauma, occlusion, or a foreign body trapped underneath the tissue flap (e.g., popcorn husk, and nut fragment) 19

Acute pericoronitis is identified by varying degrees of inflammatory involvement of the pericoronal flap and adjacent structures as well as by systemic complications. The inflammatory fluid and cellular exudate increase the bulk of the flap, which then may interfere with complete closure of the jaws and which can be traumatized by contact with the opposing jaw, thereby aggravating the inflammatory involvement 20

The resultant clinical picture is a red, swollen, suppurating lesion that is exquisitely tender, with radiating pains to the ear, the throat, and the floor of the mouth. The patient is extremely uncomfortable as a result of pain, a foul taste, and an inability to close the jaws 21

Swelling of the cheek in the region of the angle of the jaw and lymphadenitis are common findings. Trismus may also be a presenting complaint. In addition, the patient may have systemic complications such as fever, leukocytosis, and malaise. 22

COMPLICATIONS Involvement may be localized in the form of a pericoronal abscess. It may spread posteriorly into the oropharyngeal area and medially to the base of the tongue, thereby making it difficult for the patient to swallow. Depending on the severity and extent of the infection, there may be involvement of the submaxillary, posterior cervical, deep cervical, and retropharyngeal lymph nodes. Peritonsillar abscess formation, cellulitis, and Ludwigs angina are infrequent but potential sequelae of acute pericoronitis. 23

SUMMARY Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis is a painful infectious gingival disease primarily of the interdental and marginal gingiva. In pericoronitis, uncomfortable because of a foul taste and an inability to close the jaws, in the patient is extremely addition to the pain. In NUG, the zone between the marginal necrosis and the relatively unaffected gingiva usually exhibits a well- demarcated narrow erythematous zone, sometimes referred to as the linear erythema.

REFERENCES Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA. Carranza s clinical periodontology, 10th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2007. Lindhe J, Lang NP and Karring T. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. 6th ed. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; 2015. Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA. Carranza s clinical periodontology, 13th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2018. 25

THANK YOU THANK YOU 26