Acute Renal failure Acute Renal failure

Acute Renal Failure (ARF) is characterized by a decrease in glomerular filtration rate, leading to waste product accumulation. Learn about the clinical presentation, diagnosis methods, and pathophysiology of ARF.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Acute Renal failure Acute Renal failure Dr. Ashfaq Ahmad PhD Pharmacology (USM) Postdoc Pharmacology (USA)

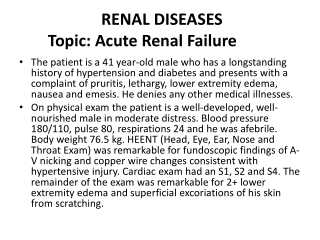

Acute renal failure Acute renal failure (ARF) is broadly defined as a decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) occurring over hours to weeks that is associated with an accumulation of waste products, including urea 6 to 24 mg/dL (2.1 to 8.5 mmol/L) and creatinine 0.74 to 1.35 mg/dL (65.4 to 119.3 micromoles/L) . Clinicians use a combination of the serum creatinine (Scr) value with change in either Scr or urine output (UOP) as the primary criteria for diagnosing ARF. GFR: 60-120 ml/min/1.73 m2 Blood urea nitrogen (BUN): 6 to 24 mg/dL

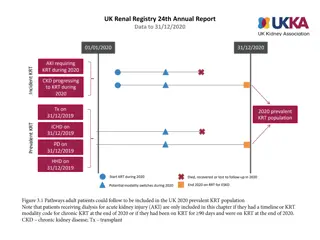

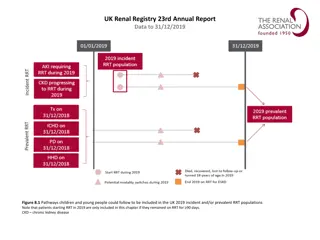

Components of the system include both GFR and UOP plus two clinical outcomes. Definitions of risk of dysfunction, injury to and failure of the kidney, loss of function, and end-stage kidney disease are included in the RIFLE acronym

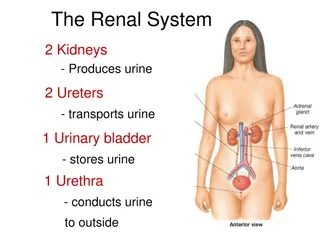

Pathophysiology ARF can be categorized as prerenal (resulting from decreased renal perfusion), intrinsic (resulting from structural damage to the kidney), postrenal (resulting from obstruction of urine flow from the renal tubule to the urethra), and functional (resulting from hemodynamic changes at the glomerulus independent of decreased perfusion or structural damage).

Clinical presentation The presentation can be subtle and depends on the setting. Outpatients often are not in acute distress; hospitalized patients may develop ARF after a catastrophic event. Symptoms in the outpatient setting include change in urinary habits, weight gain, or flank pain. Clinicians typically notice symptoms of ARF before they are detected by inpatients. Signs include edema, colored or foamy urine, and, in volume- depleted patients, orthostatic hypotension.

Diagnosis Thorough medical and medication histories, examination, assessment of laboratory values and if needed, imaging studies, are important in the diagnosis of ARF. Scr and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) cannot be used alone to diagnose ARF because they are insensitive to rapid changes in GFR and therefore may not reflect current renal function. Monitoring changes in UOP can help diagnose the cause of ARF. Acute anuria (less than 50 mL urine/day) is secondary to complete urinary obstruction or a catastrophic event (e.g., shock). Oliguria (400 to 500 mL urine/day) suggests prerenal azotemia. physical

Nonoliguric renal failure (more than 400 to 500 mL urine/day) usually results from acute intrinsic renal failure or incomplete urinary obstruction. Urinalysis can help clarify the cause of ARF. Certain laboratory parameters are helpful in the assessment of renal function with ARF

Simultaneous measurement of urine and serum chemistries and calculation of the fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) can help determine the etiology of ARF. The FENa is calculated as: where UNa = urine sodium, PCr = plasma creatinine, UCr = urine creatinine, and PNa = plasma sodium.

The FENa is calculated as: FENa RF = 4.25 (UNa: 124 PCr: 2.21 Ucr: 61 PNa: 105 where UNa = urine sodium, PCr = plasma creatinine, UCr = urine creatinine, and PNa = plasma sodium.

Exogenous administration of H2S not only provides renal protection in IRI but also improves the excretory function and morphology of the kidney.

Inhibiting NADPH oxidase by apocynin, catalase, and their combination prevents the onset of hypertension and renal injury induced by CsA.

Desired outcome The primary goal of therapy is to prevent ARF. If ARF develops, the goals are to avoid or minimize further renal insults that would delay recovery and to provide supportive measures until kidney function returns. TREATMENT PREVENTIONOF ACUTE RENAL FAILURE: Risk factors for ARF include advanced age, acute infection, preexisting chronic respiratory or cardiovascular disease, dehydration, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Uric acid nephropathy also increases risk.

Nephrotoxin administration (e.g., radiocontrast dye) should be avoided whenever possible. Strict glycemic control with insulin in diabetics has also reduced the development of ARF. Amphotericin B nephrotoxicity can be reduced by slowing the infusion rate to 24 hours MANAGEMENT OF ESTABLISHED ACUTE RENAL FAILURE No drugs have been found to accelerate ARF recovery. Therefore, patients with established ARF should be supported with nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches through the period of ARF.

Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches Supportive care goals include maintenance of adequate cardiac output and blood pressure to optimize tissue perfusion while restoring renal function to pre-ARF baseline. Medications associated with diminished renal blood flow should be stopped. Appropriate fluid replacement should be initiated. Avoidance of nephrotoxins is essential in the management of patients with ARF.

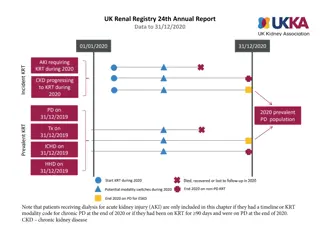

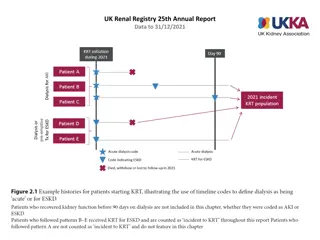

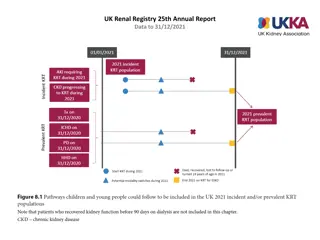

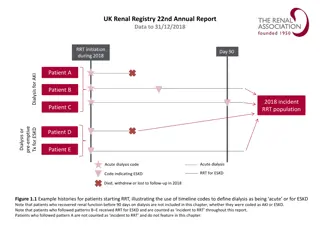

Renal replacement therapy (RRT), such as hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, maintains fluid and electrolyte balance while removing waste products (AEIOU therapy).

Intermittent RRT (e.g., hemodialysis) has the advantage of widespread availability and the convenience of lasting only 3 to 4 hours. Disadvantages include difficult venous dialysis access in hypotensive patients and hypotension due to rapid removal of large amounts of fluid. Several continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) performed as continuous hemofiltration, or both, is becoming increasingly popular. CRRT gradually removes solute resulting in better tolerability by critically ill patients. Disadvantages include limited availability, need for 24-hour nursing care, high expense, and incomplete guidelines for drug dosing hemodialysis, continuous

Pharmacologic approaches Loop diuretics have not been shown to accelerate ARF recovery or improve patient outcome; however, diuretics can facilitate management of fluid overload. The most effective diuretics are mannitol and loop diuretics. Mannitol 20% is typically started at a dose of 12.5 to 25 g IV over 3 to 5 minutes. Disadvantages include IV administration, hyperosmolality risk, and need for monitoring because mannitol can contribute to ARF.

Equipotent doses of loop diuretics (furosemide, bumetanide, torsemide, ethacrynic acid) have similar efficacy. Ethacrynic acid is reserved for sulfaallergic patients. Continuous infusions of loop diuretics appear to be more effective and to have fewer adverse effects than intermittent boluses. An initial IV loading dose (equivalent to furosemide 40 to 80 mg) should be administered before starting a continuous infusion (equivalent to furosemide 10 to 20 mg/hour). Strategies are available to overcome diuretic resistance, a common problem in patients with ARF

Agents from different pharmacologic classes, such as diuretics that work at the distal convoluted tubule (thiazides) or the collecting duct (amiloride, triamterene, spironolactone), may be synergistic when combined with loop diuretics. Metolazone is commonly used because, unlike other thiazides, it produces effective diuresis at GFR less than 20 mL/min

ELECTROLYTE MANAGEMENT AND NUTRITION THERAPY Hyperkalemia is the most common and serious electrolyte abnormality in ARF. Typically, potassium must be restricted to less than 3 g/day and monitored daily. Hypernatremia necessitating restricting daily sodium intake to no more than 3g. All sources of sodium, including antibiotics, need to be considered when calculating daily sodium intake. Phosphorus and magnesium should be monitored; neither is efficiently removed by dialysis. Enteral, but not parenteral, nutrition has been shown to improve patient outcomes. and fluid retention commonly occur,

DRUG-DOSING CONSIDERATIONS Drug therapy optimization in ARF is a challenge. Confounding variables include residual drug clearance, fluid accumulation, and use of RRTs. Volume of distribution for water-soluble drugs is significantly increased due to edema. Use of dosing guidelines for CKD does not reflect the clearance and volume of distribution in critically ill ARF patients.

ARF patients may have a higher residual nonrenal clearance than CKD patients with similar creatinine clearances; this complicates drug therapy individualization, especially with RRTs. The mode of CRRT determines the rate of drug removal, further complicating individualization of drug therapy. The rates of ultrafiltration, blood flow, and dialysate flow influence drug clearance during CRRT.

EVALUATION OF THERAPEUTIC OUTCOMES Drug concentrations should be monitored frequently because of changing volume status, changing renal function, and RRTs in patients with ARF.