China's Modern Transformation Through Western Influence

China's modernity is seen through its subjugation to the West's political, military, and economic control. The birth of the modern Orient occurred through invasion, defeat, and exploitation by the West.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

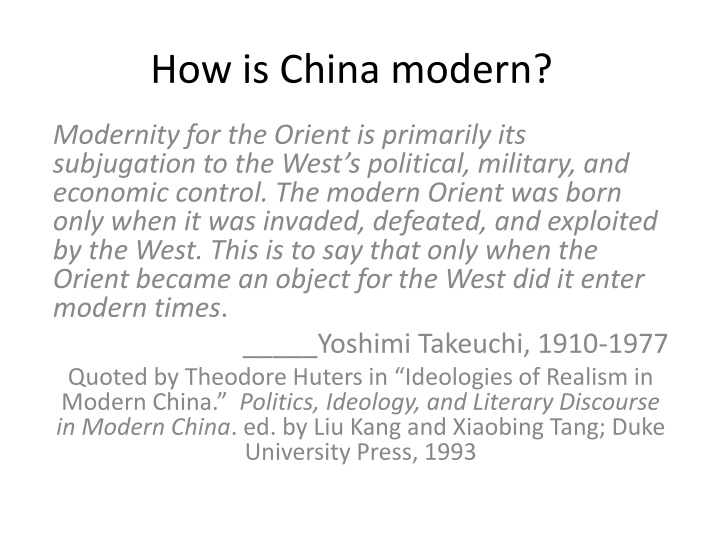

How is China modern? Modernity for the Orient is primarily its subjugation to the West s political, military, and economic control. The modern Orient was born only when it was invaded, defeated, and exploited by the West. This is to say that only when the Orient became an object for the West did it enter modern times. _____Yoshimi Takeuchi, 1910-1977 Quoted by Theodore Huters in Ideologies of Realism in Modern China. Politics, Ideology, and Literary Discourse in Modern China. ed. by Liu Kang and Xiaobing Tang; Duke University Press, 1993

China and the West But in India, it [despotism] is normal: for here there is no sense of personal independence with which a state of despotism could be compared, and which would raise revolt in the soul; nothing approaching even a resentful protest against it, is left, except the corporeal smart, and the pain of being deprived of absolute necessaries and of pleasure. In the case of such a people, therefore, that which we call history is not to be looked for. This [Hinduism] makes them incapable of writing history; all that happens is dissipated in their minds into confused dreams. ___Friedrich Hegel, The Philosophy of History, 1805

Modern China and its plight If intercourse between Western nations and China is to be fruitful, we must cease to regard ourselves as missionaries of a superior civilization, or, worse still, as men who have a right to exploit, oppress, and swindle the Chinese because they are an "inferior" race. I do not see any reason to believe that the Chinese are inferior to ourselves; and I think most Europeans, who have any intimate knowledge of China, would take the same view. . . . Progress and efficiency, for example, make no appeal to the Chinese, except to those who have come under Western influence. By valuing progress and efficiency, we have secured power and wealth; by ignoring them, the Chinese, until we brought disturbance, secured on the whole a peaceable existence and a life full of enjoyment. Our industrialism, our militarism, our love of progress, our missionary zeal, our imperialism, our passion for dominating and organizing, all spring from a super-flux of the itch for activity. The Chinese have discovered, and have practiced for many centuries, a way of life which, if it could be adopted by all the world, would make all the world happy. We Europeans have not. Our way of life demands strife, exploitation, restless change, discontent and destruction. Efficiency directed to destruction can only end in annihilation, and it is to this consummation that our civilization is tending, if it cannot learn some of that wisdom for which it despises the East. _______Bertrand Russell, The Problems of China, 1922

Whats wrong with traditional China The ubiquitous potential presence of a balanced, totalized, dimension of meaning may partially explain why a fully realized sense of the tragic does not materialize in Chinese narrative. . But in each case the implicit understanding of the logical interrelation between these fictional characters particular situation and the overall structure of existential intelligibility serves to blunt the pity and fear the reader experiences as he witnesses their individual destinies. In other words, Chinese narrative is replete with individuals in tragic situations, but the secure inviolability of the underlying affirmation of existence in its totality precludes the possibility of the individual s tragic fate taking on the proportions of a cosmic tragedy. Instead, the bitterness of the particular case of mortality ultimately settles back into ceaseless alternation of patterns of joy and sorrow, exhilaration and despair, which go to make up an essentially affirmative view of the universe of experience. Andrew Plaks, Chinese Narrative

Whats wrong with traditional China The late Dr. Hu Shih, eminent historian of Chinese thought and culture, used to say with sly delight that centuries of Christian missionaries had been frustrated and chagrined by the apparent inability of Chinese to take sin seriously. Were we to work out fully all the consequences for Chinese society of the model offered by an organismic cosmos functioning through the dynamism of harmony, we might well be able to relate the absence of a sense of sin to it. For in such a cosmos there can be no parts wrongfully present; everything that exists belongs, even if no more appropriately than as the consequence of a temporary imbalance, a disharmony. Evil as a positive or active force cannot exist; much less can it be frighteningly personified. No devils can struggle with good forces for mastery of humans and the universe, and people s errors, unlike sin in other worlds, can neither offend personal gods not threaten a person s individual existence. The question of immortality in a future that really counts if one is lucky enough or good enough to transcend the material present reality does not even arise. The being true in the Great Tradition, countertendencies in the popular religions in China s highly congruent culture were correspondingly weakened. The consequence of such a definition of the problem of evil for the Chinese character seems to be something like the issue at stake in the frequently encountered distinction between shame cultures and guilt cultures. Whether this formula, derived by anthropologists from observations of relatively simple cultures, will have lasting value when applied to a civilization as complex as that of traditional China may be questioned. But it suggests that further hypotheses about Chinese traditional character and personality types might well be guided by some reference to a cosmology which apparently releases people from the mechanical workings of fear and sin doctrines, and offers them a less threatened and less threatening personal relationship to their cosmos. Yet Chinese ethical philosophy in all periods stresses the necessity to engage in self -examination and self-correction; the philosophic foundations for a moral responsibility were not lacking. ___Federick Mote, Intellectual Foundations of China, PP. 21-22

Whats wrong with traditional China For instance, the Frenchman Maupassant s Une vie is human literature about the animal passions of man; China s Prayer Mat of Flesh, however, is a piece of non-human literature. The Russian Kuprin s novel Jama is literature describing the lives of prostitutes, but China s Nine-tailed Tortoise is non-human literature. The difference lies merely in the different attitudes conveyed by the work, one is dignified and one is profligate; one has aspirations for human life and therefore feels grief and anger in the face of inhuman life, whereas the other is complacent about human life, and the author even seems to derive a feeling of satisfaction from it, and in many cases to deal with his material in an attitude of amusement and provocation. In one simple sentence: the difference between human and non-human literature lies in the attitude that informs the writing; whether it affirms human life or inhuman life. Zhou Zuoren, Humane Literature 1918

Whats wrong with traditional China Chinese literature today is lifeless and stale, unable to stand next to that of Europe. . . . . The problem of Confucianism has been attracting much attention in the nation: this is the first indication of the revolution in ethics and morality. ... The classical literature is pompous and pedantic and has lost the principles of expressiveness and realistic description. Eremitic literature is highly obscure and abstruse and is self-satisfied writing that provides no benefit to the majority of its readers. In form, Chinese literature has followed old precedents; it has flesh without bones and body without soul. It is a decorative and not a practical product. In content, its vision does not go beyond kings, officials, spirits, ghosts, and the fortunes or misfortunes of individuals. As for the universe, or human life, or society--they are simply beyond its ken. Such are the common failings of these three kinds of literature. Chen Duxiu, On Literary Revolution 1917

Whats wrong with traditional China One absolutely central aspect of the concept of moral autonomy in Western philosophy involves distinguishing morality proper from conventional mores. This basic element of autonomy in Western ethical theory generates the distinction between codes of etiquette, fashion, and customs, on the one hand, and morality on the other. Etiquette, fashion and customs are products of history. They are, from moral point of view, accidental. One can always ask whether one ought to follow accepted and established prescriptions. It does not follow from mere existence of any such system that its prescriptions are morally correct. It may fairly be asked if Confucius s traditionalist political philosophy has this distinct concept of morality at all. __Chad Hansen, Punishment and Dignity in China in Individualism and Holism

May Fourth Anti-Traditionalist Attitude This new rhetoric is deceptively simple: since China s backwardness had deep roots in Chinese polity, society, and culture, the total transformation of Chinese-ness is a precondition for China s modernization. _____Tu Wei-ming, ed. The Living Tree, The Changing Meaning of Being Chinese Today, Stanford UP, 1994

Lu Xun and May Fourth New Culture Movement Abolition of the Civic Service Exam in 1905 May Fourth, 1919 Mr. De and Mr. Sai Arthur Smith Chinese Characteristics Iconoclasm Writer as the conscience and soul of the nation, Ambivalence, the League of Left-Wing Writers, debate between Hu Shi and Li Dazhao,