Christian Beliefs and Ethical Perspectives on Hope and Eschatology

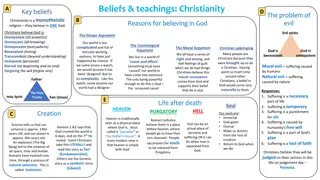

Christian beliefs and ethics intertwine with notions of hope, eschatology, and the future, shaping perspectives on life, love, humanity, and the planet. Contemplating the role of resurrection, judgment, and everlasting life influences ethical considerations and the understanding of suffering. The evolution of eschatology, from Hebrew Bible references to Jesus' teachings, reflects shifts in beliefs about the afterlife and hope for resurrection. Explore the intricate connections between faith, ethics, and the anticipation of future events.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

The Future of Jesus Christ Jesus Christ: Past, Present and Future London Jesuit Centre

Expectation and the emergence of eschatology Jesus Christ: Past, Present and Future

Hope, expectation and the future Consider the kinds of hopes, or expectations that you have for: - Your own life - The lives of those you love - The human race - Planet earth

Hope, expectation and the future He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead and his kingdom will have no end. [. . .]I look forward to the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. Amen. What role do these ideas play in your hopes expectations for: - Your own life? - The lives of those you love - The human race - Planet earth

Ethics and eschatology How does the question how should we live? relate to the question what can we hope for? Is it possible to deal with these things separately? Very easy to see why we might want to . - Belief in life beyond death is beyond proof! - Specific eschatological beliefs difficult to argue for (without belief in revelation); - (Since Kant, it has often been held that the Christian message should be understood in such a way that it does not first depend on proving something like life after death); - So if Christian ethics can be made attractive, plausible, etc. without reference to these beliefs, then surely we can give a better account of Christianity to those outside it. - (This is an old impulse; referred to by Tertullian see how those Christians love each other )

Ethics and eschatology But is this possible? For example, Eleonore Stump, the Catholic philosopher, makes an important point in one of her recent books. There she examines Christian beliefs and attitudes towards suffering. Christian attitude towards earthly suffering is incomprehensible without reference to beliefs about everlasting life; Just as we would be unable to understand what is happening in a hospital visit without reference to what happens after the hospital visit. What do you make of that thought?

The emergence of eschatology Intriguingly, for the most part, the Hebrew Bible has little to say about life beyond, or after death Interest in the future focuses on descendants; Sheol , the realm of the dead, is not desirable but something to be rescued from; Spiritual life true worship is not intrinsically at odds with bodily existence (so bodily life is not something to be freed from) Nevertheless, by the time of Jesus, the idea of hope for resurrection was relatively common. How did this happen?

The emergence of eschatology Eschatology emerges from a need that was felt within Jewish thinking. Put simplistically: - God is the creator of all (the only true God); - God has promised blessing to all, via the covenant with Israel; - But God s promises are not yet fulfilled, and God s covenant is (sometimes) in question! - Because Israel is not always faithful - Because (maybe) God does not seem presently, faithful So Jewish hopes (for, e.g., resurrection and a last judgement , etc.) emerge from this tension: Either something has to give, or something has to happen

The emergence of eschatology A rich range of eschatological expectations present at the time of Jesus. According to NT Wright, there are a number of themes/images: The Day of the LORD Coming of the kingdom of God Victory over evil (rulers) and pagan idolatry The end of (spiritual) exile The coming of the Messiah The new Exodus; The resurrection of the dead; The return of the Glory of the LORD

Pauls thinking draws very deeply on these themes, but innovates in one crucial respect: The emergence of eschatology the complex event for which Israel had hoped had already happened in the events of Jesus of Nazareth. Jesus resurrection indicated not just that something extraordinary had happened, but what that extraordinary thing was: the anticipation, breaking into the scene of ongoing history, of the ultimate End. [. . .] what Israel had expected God to do for all his people at the end of time, God has done for the Messiah in the middle of time. (Wright, Fresh Perspectives on Paul, p. 136)

Hope and The People of God Jesus Christ: Past, Present and Future

The eschatological reign of God The word Kingdom does not mean a realm, or province; rather, it is something more like a reign or rule . Emerges from Jewish ideas about the kingship of God, e.g. Psalm 47: Clap your hands, all you peoples; shout to God with loud songs of joy. For the Lord, the Most High, is awesome, a great king over all the earth. [. . .] For God is the king of all the earth; sing praises with a psalm.

The eschatological reign of God But historical experiences led to a modification of this idea: In the course of its history, however, Israel learned through painful experience that the belief in the Lordship of God contrasted sharply with the world as it was. The result, particularly from the time of the great writing prophets, was a definite eschatologization of that belief. All the great saving acts of the past such as the making of the covenant and the exodus are now expected in intensified form in the future. (Kasper, Jesus the Christ, 62). But this expectation was eventually not just for a future fulfilment, but for a different, more definitive kind of fulfilment a new age.

The eschatological reign of God Jesus complicates matters by saying that these eschatological hopes are being fulfilled now, and in his own life, whilst still cultivating expectation, watchfulness, etc. about events to come . Some scholars attempt to show that Jesus had a consistent eschatology (where the Kingdom is either completely arrived, or is expected to arrive in full in the near future). But most scholars agree that the ambiguity was present from the start: the Kingdom was understood by Jesus to be both already here, but not yet present in full: Jesus message about the coming of the Kingdom of God contains an excess of promise; it creates a hope which is still unfulfilled after the message has been proclaimed. The hope will not be fulfilled until God is finally all in all (cf 1 Cor 15.28). (Kasper, Jesus the Christ, 66).

Yves Congar (1904- 1995) In his book The Mystery of the Church, published before the Second Vatican Council, Congar connects the meaning of two marks of the Church one, catholic like this: In Christ the fullness of life is, indeed, restored and the result of this restoration, as brought about in space and time, is simply the Church. Consequently, the Church is presented to us as from the very beginning essentially catholic, that is to say embracing the whole universe of being and of beings in unity, catholic by reason of a catholicity it derives from its source, Christ, in whom dwells the fullness of the divine energy capable of reconciling, purifying, unifying and transfiguring the world. (67) This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

Yves Congar (1904- 1995) For Congar, we can only understand why we should say that the church is one and catholic because of what we first have to understand about what God as done in and through Christ. He writes: The Church is one because Christ is one of whom it is the body; it is holy because the being Christ gives it is something holy, something heavenly, pneumatic ; it is Catholic because its head [i.e. Christ] has the power to communicate it a life and a force capable of reuniting through its means, in him, all things, those in heaven and those on the earth. (68) This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

Yves Congar (1904-1995) On the one hand the Church as something that shares the oneness and universality of Christ is something that God has brought about (in that sense in comes down from heaven to earth). On the other hand, the oneness and catholicity are to be brought about by human activity they are the church s mission. In this way, the mystery of the mystical Body, like that of the Kingdom, brings us in contact with a twofold and antithetical truth. Everything is already fulfilled in Christ; the Church is simply the manifestation of what is in him, the visible reality animated by his Spirit. Yet, we have still to realize Christ and build up his body. (70) This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

The eschatological church in Lumen Gentium ) Paragraph 9 narrates a history of salvation, from creation, through the calling of the people of Israel, to Christ At all times and in every race God has given welcome to whosoever fears Him and does what is right. God, however, does not make men holy and save them merely as individuals, without bond or link between one another. Rather has it pleased Him to bring men together as one people, a people which acknowledges Him in truth and serves Him in holiness. He therefore chose the race of Israel as a people unto Himself. [. . .] All these things, however, were done by way of preparation and as a figure of that new and perfect covenant, which was to be ratified in Christ, and of that fuller revelation which was to be given through the Word [. . .] Christ instituted this new covenant, the new testament, that is to say, in His Blood,(87) calling together a people made up of Jew and gentile, making them one, not according to the flesh but in the Spirit. This was to be the new People of God.

The eschatological church in Lumen Gentium ) Another important emphasis in the document is the relationship between the unity of the Church, and the unity of the human race as a whole. Paragraph 13 begins like this: All men are called to belong to the new people of God. Wherefore this people, while remaining one and only one, is to be spread throughout the whole world and must exist in all ages, so that the decree of God's will may be fulfilled. In the beginning God made human nature one and decreed that all His children, scattered as they were, would finally be gathered together as one. (Compare Ephesians 1: 10, 23-24)

The eschatological church in Lumen Gentium ) Then the section concludes with the following: All men are called to be part of this catholic unity of the people of God which in promoting universal peace presages it. And there belong to or are related to it in various ways, the Catholic faithful, all who believe in Christ, and indeed the whole of mankind, for all men are called by the grace of God to salvation. So commitment to the idea that the Church is one is connected with commitment to a certain view of human beings as such: that humans are made for harmony with one another. The Church is defined by a certain kind of unity, which is also its mission to bring about in the human race as a whole.

Hope and the unquiet heart Jesus Christ: Past, Present and Future

Hope as a contending emotion For Aquinas hope presupposes desire, but is distinct from it. Hope is 'directed by the power of desire' to its object, which is determined by four conditions: First, that it is something good; since, properly speaking, hope regards only the good; in this respect, hope differs from fear, which regards evil. Secondly, that it is future; for hope does not regard that which is present and already possessed: in this respect, hope differs from joy which regards a present good. Thirdly, that it must be something arduous and difficult to obtain, for we do not speak of any one hoping for trifles, which are in one's power to have at any time [. . .]Fourthly, that this difficult thing is something possible to obtain: for one does not hope for that which one cannot get at all: and, in this respect, hope differs from despair. (ST1a2ae 40.2)

Hope as a contending emotion So hope is first of all an emotion, but it is still subject to judgements that we make through reason, or arrive at through experience: whatever makes a man think that something is possible for him is a cause of hope [. . .] This is also the way in which experience causes hope; through experience a man may discover that something is within his power which he had thought of as previously impossible. But from another angle experience can cause hope to fail. [. . .] experience may bring one to judge that what he had thought possible is in fact not so.

Hope as a contending emotion This means that hope will be shaped by understanding and experience But potentially in opposing ways: - I might judge that something is possible when it is not, meaning that I hope mistakenly, or foolishly; - I might judge that something is impossible when it is not, meaning that I lose hope; Hence it is quite possible, as Aquinas admits, that the young and the drunk are particularly prone to hope! It also means that hope is intimately connected to our beliefs: About ourselves; About the human race; About reality as such (and what is possible within it)

Hope as a (theological) virtue unlike the natural and acquired virtues formed through habituation and effort, hope is a supernatural and infused virtue gratuitously poured out by grace. Like faith and charity, hope is also a theological virtue in that its immediate object is God. But whereas faith knows God as first truth and charity loves God as the universal good, hope loves God as our personal good namely, as our perfection and beatitude. (David Elliott, on Aquinas)

Hope as a (theological) virtue And hope focuses on God in two different ways: God as that for which we long; God as that on which we rely. The basic practice of hope, therefore, might be summarized as a combination of longing and leaning. By hope we long for God whom we seek as the source of our beatitude, and we rely upon grace to sustain us through the joys and challenges of our earthly pilgrimage. (Elliot on Aquinas) This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

Hope as a (theological) virtue So our hoping could go wrong either: because we hope for something that is less than God (this would be a kind of idolatry, supposing something other than God to satisfy our deepest longing); because we don t place our hope in/on God; presumption (grounds hope in ourselves, or in something that we presume that we have control over, e.g. social position, political influence; history; ability) despair (fails to trust God as source of hope)

Rahner: Into the uncontrollability of God Hope implies the one basic character which is the common factor in the mutual interplay of truth and love: the enduring attitude of outwards from self into the uncontrollability of God. [. . .] In the light of this, both presumption and despair are, at basis, the refusal of the subject to allow himself to be grasped by the uncontrollability and to be drawn out of himself by it. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA

Rahner: Into the uncontrollability of God But what is the basic quality of our attitude towards God? How does this attitude come into our hope? Would hope remain even in the life of the world to come? the response to and acceptance of God as truth and as love have an interior unity and a common source in the one radical attitude which draws us out of ourselves into that which is utterly beyond our control. So we can see that hope would remain even in the life of the world to come, when we know even as we are known . Hope is not so much our response to specific beliefs (e.g. that Christ will return; that the dead will be raised) but the basic posture of a Christian to be oriented towards an uncontrollable mystery. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA

Problems with hope? Perhaps most obviously, the Christian virtue of hope is tied to ideas about heaven, or the life of the world to come. This is often derided as an opiate for earthly misery; a foothold for gloomy asceticism; a distraction from social justice; and a brake on human progress.

Problems with hope? For Miguel De La Torre, the theological appeal to hope often obscures real conditions, and stops us from engaging in meaningful change: hope whitewashes reality, preventing praxis from formulating. As a statement of unfounded belief, hope is an illusion beyond critical examination, serving an important middle-class purpose, providing a quasi-religious contentment in the midst of oppression. All too often, hope becomes an excuse not to deal with the reality of injustice.

Problems with hope? And the language of hope can be secretly disempowering: To hope is to become dependent on the metaphysical to lead toward some utopian future without our need to participate and make the determined future a reality. [ . . .] The hope of survival means I have something in the future to lose, and protecting the little I imagine I have blocks me from the radical actions required if drastic change is desired.

Problems with hope? For Antony Pinn, the theological category of hope is inevitably dualistic; it is inconsistent with a lucid embrace of experience s materiality . Instead, he wants a moral humanism that maintains attention to current circumstances and offers only what these conditions allow to be said.

For Rousseau, the emphasis on heaven is tied to passivity: Christianity preaches only servitude and dependence. Its spirit is so favourable to tyranny that it always profits by such a r gime. Genuine Christians are made to be slaves, and they know it and don t much mind: this short life counts for too little in their eyes. Problems with hope? If the person who has the power abuses it, that is the whip God uses to punish his children. There would be scruples about driving out the usurper: it would involve disturbing public peace, using violence, spilling blood; none of this squares with Christian gentleness; and anyway what does it matter in this vale of sorrows whether we are free men or serfs? The essential thing is to get to heaven, and resignation i.e. putting up with hardship patiently and without complaining is just one more way of getting there.

Moltmann, Theology of Hope the eschatological outlook is characteristic of all Christian proclamation, of every Christian existence and of the whole Church. There is therefore only one real problem in Christian theology, which is own object forces upon it, and which in turn forces on mankind and on human thought: the problem of the future. [. . .] But how can Christian eschatology give expression to the future? Christian eschatology does not speak of the future as such. It sets out from a definite reality in history and announces the future of that reality, its future possibilities and its power of the future. Christian eschatology speaks of Jesus Christ and his future. (p. 17). This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

Moltmann, Theology of Hope The resurrection of Christ is not primarily about the salvation of individual souls; it is a foretaste of the eschatological transformation of our entire human context. He writes: To believe means to cross in hope and anticipation the bounds that have been penetrated by the raising of the crucified. ... It sees in the resurrection of Christ not the eternity of heaven, but the future of the very earth on which his cross stands. It sees in him the future of the very humanity for which he died. (p. 21) This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

Moltmann, Theology of Hope In the face of these kinds of critiques, Jurgen Moltmann is keen to show that Christian hope is not a flight from the trials of earthly life: Faith, wherever it develops into hope, causes not rest but unrest, not patience but impatience. It does not calm the unquiet heart, but is itself this unquiet heart in man. Those who hope in Christ can no longer put up with reality as it is, but begin to suffer under it, to contradict it. Peace with God means conflict with the world, for the goad of the promised future stabs inexorably into the flesh of every unfulfilled present. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

Moltmann, Theology of Hope Equally, Christian hope is distinguished from an attitude that tries, come what may, to calmly accept and dwell in the present moment. Christian hope is based on the God who creates ex nihilo (from nothing), and who makes all things new : The hope that is staked on the creator ex nihilo becomes the happiness of the present when it loyally embraces all things in love, abandoning nothing to annihilation but bringing to light how open all things are to the possibilities in which they can live and shall live. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

Moltmann, Theology of Hope Only hope can take seriously the possibilities with which reality is fraught [. . .] Thus the despair which imagines it has reached the end of its tether proves to be illusory, as long as nothing has yet come to an end but everything is still full of possibilities. - So hope is somehow in-tune with reality, precisely because everything is always becoming, seeking fulfilment, but nothing is yet finished. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

Moltmann, The Coming of God Christian eschatology emerges from a need that was felt within Jewish thinking: - God is the creator of all; - God has promised blessing to all, via the covenant with Israel; - But God s faithfulness is not yet manifest! Cosmic eschatology is not required for the sake of some universalism or other; it is necessary for God s sake. There are not two Gods, a Creator God and a Redeemer God. There is one God. It is for his sake that the unity of redemption and creation has to be thought. (p. 259) This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

Moltmann, The Coming of God The redemption of humanity is aligned towards a humanity whose existence is still conjoined with nature. Consequently it is impossible to conceive of any salvation for men and women without a new heaven and a new earth . There can be no eternal life for human beings without the change in the cosmic conditions of life. (p. 260) - As he admits, the difficulties about not just hoping this but thinkingit too are considerable ! This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND