Class I: Ratione personae

Formal criteria, admissibility criteria, and time limits associated with the Complaint Procedure under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Delve into exhaustion of domestic remedies, locus standi, and relevant case law developments. Learn about the importance of Ratione Personae, Ratione Loci, and other material criteria in submitting a complaint.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Overview (1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR (2) Complaint procedure: Travaux pr paratoires (3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR (4) Complaint procedure: Recent developments

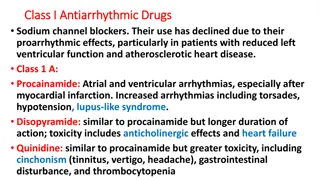

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Formal criteria Exhaustion Time limit Substantially the same Abuse of right Locus standi De Minimis regel Manifestly ill-founded Material criteria Ratione Personae Ratione Loci Ratione Temporis Ratione Materiae

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Formal criteria ARTICLE 35 Admissibility criteria Exhaustion Time limit 1. The Court may only deal with the matter after all domestic remedies have been exhausted, Substantially the same Abuse of right Locus standi De Minimis regel Manifestly ill-founded Material criteria Ratione Personae Ratione Loci Ratione Temporis Ratione Materiae

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Formal criteria ARTICLE 35 Admissibility criteria Exhaustion Time limit 1. The Court may only deal with the matter after all domestic remedies have been exhausted, according recognised rules of international law, and within a period of six months from the date on which the final decision was taken. Substantially the same to the generally Abuse of right Locus standi De Minimis regel Manifestly ill-founded Material criteria Ratione Personae Ratione Loci Ratione Temporis Ratione Materiae

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Formal criteria ARTICLE 35 Admissibility criteria Exhaustion 2. The Court shall not deal with any application submitted under Article 34 that (a) is anonymous; or (b) is substantially the same as a matter that has already been examined by the Court or has already been submitted to another procedure of international investigation or settlement and contains no relevant new information. Time limit Substantially the same Abuse of right Locus standi De Minimis regel Manifestly ill-founded Material criteria Ratione Personae Ratione Loci Ratione Temporis Ratione Materiae

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Formal criteria ARTICLE 35 Admissibility criteria Exhaustion Time limit Substantially the same 3. The Court shall declare inadmissible any individual application submitted under Article 34 if it considers that: (a) the application is incompatible with the provisions of the Convention Protocols thereto, manifestly ill-founded, or an abuse of the application; or. Abuse of right Locus standi De Minimis regel or the Manifestly ill-founded right of individual Material criteria Ratione Personae Ratione Loci Ratione Temporis Ratione Materiae

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Formal criteria ARTICLE 35 Admissibility criteria Exhaustion Time limit Substantially the same 3. The Court shall declare inadmissible any individual application submitted under Article 34 if it considers that: (b) the applicant significant disadvantage, unless respect for human rights as defined in the Convention and the Protocols examination of the application on the merits and provided that no case may be rejected on this ground which has not been duly considered by a domestic tribunal. Abuse of right Locus standi has not suffered a De Minimis regel Manifestly ill-founded thereto requires an Material criteria Ratione Personae Ratione Loci Ratione Temporis Ratione Materiae

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Formal criteria ARTICLE 35 Admissibility criteria Exhaustion Time limit Substantially the same 3. The Court shall declare inadmissible any individual application submitted under Article 34 if it considers that: (b) the applicant significant disadvantage, unless respect for human rights as defined in the Convention and the Protocols examination of the application on the merits and provided that no case may be rejected on this ground which has not been duly considered by a domestic tribunal. Abuse of right Locus standi De Minimis regel has not suffered a Manifestly ill-founded thereto requires an Material criteria Ratione Personae Ratione Loci Ratione Temporis Ratione Materiae

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Formal criteria ARTICLE 35 Admissibility criteria Exhaustion Time limit Substantially the same 3. The Court shall declare inadmissible any individual application submitted under Article 34 if it considers that: (a) the application is incompatible with the provisions of the Convention Protocols thereto, manifestly ill-founded, or an abuse of the right of individual application; or. Abuse of right Locus standi De Minimis regel Manifestly ill-founded or the Material criteria Ratione Personae Ratione Loci Ratione Temporis Ratione Materiae

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Formal criteria Admissibility Guide ECHR Exhaustion Time limit 191. Compatibility ratione personae requires the alleged violation of the Convention to have been committed by a Contracting State or to be in some way attributable to it. Substantially the same Abuse of right Locus standi De Minimis regel Manifestly ill-founded Material criteria Ratione Personae Ratione Loci Ratione Temporis Ratione Materiae

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Formal criteria Admissibility Guide ECHR Exaustion Time limit 216. Compatibility ratione loci requires the alleged violation of the Convention to have taken place within the jurisdiction of the respondent State or in territory effectively controlled by it Substantially the same Abuse of right Locus standi De Minimis regel Manifestly ill-founded Material criteria Ratione Personae Ratione Loci Ratione Temporis Ratione Materiae

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Formal criteria Admissibility Guide ECHR Exhaustion Time limit 225. In accordance with the general rules of international law (principle of non- retroactivity of treaties), the provisions of the Convention do not bind a Contracting Party in relation to any act or fact which took place or any situation which ceased to exist before the date of the entry into force of the Convention in respect of that Party Substantially the same Abuse of right Locus standi De Minimis regel Manifestly ill-founded Material criteria Ratione Personae Ratione Loci Ratione Temporis Ratione Materiae

Signature Ratification Entry into Force Albania 13/07/1995 02/10/1996 02/10/1996 Andorra 10/11/1994 22/01/1996 22/01/1996 Armenia 25/01/2001 26/04/2002 26/04/2002 Austria 13/12/1957 03/09/1958 03/09/1958 Azerbaijan 25/01/2001 15/04/2002 15/04/2002 Belgium 04/11/1950 14/06/1955 14/06/1955 Bosnia and Herzegovina 24/04/2002 12/07/2002 12/07/2002 Bulgaria 07/05/1992 07/09/1992 07/09/1992 Croatia 06/11/1996 05/11/1997 05/11/1997 Cyprus 16/12/1961 06/10/1962 06/10/1962 Czech Republic 21/02/1991 18/03/1992 01/01/1993 Denmark 04/11/1950 13/04/1953 03/09/1953 Estonia 14/05/1993 16/04/1996 16/04/1996 Finland 05/05/1989 10/05/1990 10/05/1990 France 04/11/1950 03/05/1974 03/05/1974

Signature Ratification Entry into Force Georgia 27/04/1999 20/05/1999 20/05/1999 Germany 04/11/1950 05/12/1952 03/09/1953 Greece 28/11/1950 28/11/1974 28/11/1974 Hungary 06/11/1990 05/11/1992 05/11/1992 Iceland 04/11/1950 29/06/1953 03/09/1953 Ireland 04/11/1950 25/02/1953 03/09/1953 Italy 04/11/1950 26/10/1955 26/10/1955 Latvia 10/02/1995 27/06/1997 27/06/1997 Liechtenstein 23/11/1978 08/09/1982 08/09/1982 Lithuania 14/05/1993 20/06/1995 20/06/1995 Luxembourg 04/11/1950 03/09/1953 03/09/1953 Malta 12/12/1966 23/01/1967 23/01/1967 Monaco 05/10/2004 30/11/2005 30/11/2005 Montenegro 03/04/2003 03/03/2004 06/06/2006 Netherlands 04/11/1950 31/08/1954 31/08/1954

Signature Ratification Entry into Force North Macedonia 09/11/1995 10/04/1997 10/04/1997 Norway 04/11/1950 15/01/1952 03/09/1953 Poland 26/11/1991 19/01/1993 19/01/1993 Portugal 22/09/1976 09/11/1978 09/11/1978 Republic of Moldova 13/07/1995 12/09/1997 12/09/1997 Romania 07/10/1993 20/06/1994 20/06/1994 Russian Federation 28/02/1996 05/05/1998 05/05/1998 San Marino 16/11/1988 22/03/1989 22/03/1989 Serbia 03/04/2003 03/03/2004 03/03/2004 Slovak Republic 21/02/1991 18/03/1992 01/01/1993 Slovenia 14/05/1993 28/06/1994 28/06/1994 Spain 24/11/1977 04/10/1979 04/10/1979 Sweden 28/11/1950 04/02/1952 03/09/1953 Switzerland 21/12/1972 28/11/1974 28/11/1974 Turkey 04/11/1950 18/05/1954 18/05/1954

Signature Ratification Entry into Force Ukraine 09/11/1995 11/09/1997 11/09/1997 United Kingdom 04/11/1950 08/03/1951 03/09/1953

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Formal criteria Admissibility Guide ECHR Exaustion Time limit 252. The compatibility ratione materiae with the Convention of an application or complaint derives from the Court s substantive jurisdiction. For a complaint to be compatible ratione materiae with the Convention, the right relied on by the applicant must be protected by the Convention and the Protocols thereto that have come into force. Substantially the same Abuse of right Locus standi De Minimis regel Manifestly ill-founded Material criteria Ratione Personae Ratione Loci Ratione Temporis Ratione Materiae

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Class I > Ratione personae (locus standi & de minimis) Class II > Ratione materiae

(1) Complaint procedure under the ECHR Applications will be declared incompatible ratione personae with the Convention on the following grounds: if the applicant lacks standing as regards Article 34 of the Convention if the applicant is unable to show that he or she is a victim of the alleged violation if the application is brought against an individual if the application is brought directly against an international organisation which has not acceded to the Convention if the complaint involves a Protocol to the Convention which the respondent State has not ratified

(2) Complaint procedure: Travaux pr paratoires ARTICLE 33 Inter-State cases Any High Contracting Party may refer to the Court any alleged breach of the provisions of the Convention and the Protocols thereto by another High Contracting Party. ARTICLE 34 Individual applications The Court may receive applications from any person, non-governmental organisation or group of individuals claiming to be the victim of a violation by one of the High Contracting Parties of the rights set forth in the Convention or the Protocols thereto. The High Contracting Parties undertake not to hinder in any way the effective exercise of this right.

(2) Complaint procedure: Travaux pr paratoires Dicussions when drafting: 1. Should there be a European Convention? 2. How should such a Convention look like? 3. Should there be a Commission? 4. Should there be a Court? 5. Should individuals have a right to complain? 6. Should the right to education, the right to property and right to free elections be included in the Convention?

(2) Complaint procedure: Travaux pr paratoires 1. Should there be a European Convention? Yes, Europe should have its own list of rights and have a more precise and effective mechanism of enforcement No, we already have a Universal Declaration of Human Rights and we should not have a document that could conflict with it Compromise Yes, there is a Convention, but signing was optional

(2) Complaint procedure: Travaux pr paratoires 2. How should such a Convention look like? Ennumeration (Alternative A) Precise definition (Alternative B) Compromise Precise definition was taken as basis, but the rights ennumerated in Alternative A and the other provisions were merged

(2) Complaint procedure: Travaux pr paratoires 3. Should there be a Commission? Yes, the Commission could investigate the facts of the matter, its judgement would have a reputational effect and the Commission could try and it could stimulate a settlement No, there is no need for a supervisory mechanism within the Council of Europe, both because countries had mechanisms in place and because there was the International Court of Justice in The Hague Compromise Yes, there is a Commission, but its authority was dependent on ratification by each individual Member State

(2) Complaint procedure: Travaux pr paratoires 4. Should there be a Court? Yes, a Court could impose sanctions and penalties, meaning that there would be an effective enforcement-mechanism for the ECHR No, this would limmit the national authority + if there was a truly totalitarian regime, it would not be stopped by a European Court + the judgements by the Commission would be sufficient Compromise Again, the Court s authority was optional

(2) Complaint procedure: Travaux pr paratoires 5. Should individuals have a right to complain? Yes, otherwise the ECHR would not be effective as a human rights guarantee No, fear of higher numbers of complaints + fear of abuse of right + fear of many small, individual matters put forward Compromise: Both inter-state & indivdiual complain right, but individuals only allowed to pettition to the Commission

(2) Complaint procedure: Travaux pr paratoires

(2) Complaint procedure: Travaux pr paratoires 6. Should the right to education, the right to property and right to free elections be included in the Convention? Yes, because important (influence on education can be abused by totalitarian states and individual property was challenged by communist regimes) No, because socio-economic rights and not civil-political rights Compromise Included in the First Optional Protocol to the Convention

(2) Complaint procedure: Travaux pr paratoires 1eProtocol ARTICLE 1 Protection of property Every natural or legal person is entitled to the peaceful enjoyment of his possessions. No one shall be deprived of his possessions except in the public interest and subject to the conditions provided for by law and by the general principles of international law. The preceding provisions shall not, however, in any way impair the right of a State to enforce such laws as it deems necessary to control the use of property in accordance with the general interest or to secure the payment of taxes or other contributions or penalties. ARTICLE 2 Right to education No person shall be denied the right to education. In the exercise of any functions which it assumes in relation to education and to teaching, the State shall respect the right of parents to ensure such education and teaching in conformity with their own religious and philosophical convictions. ARTICLE 3 Right to free elections The High Contracting Parties undertake to hold free elections at reasonable intervals by secret ballot, under conditions which will ensure the free expression of the opinion of the people in the choice of the legislature.

(3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR ARTICLE 33 Inter-State cases Any High Contracting Party may refer to the Court any alleged breach of the provisions of the Convention and the Protocols thereto by another High Contracting Party. ARTICLE 34 Individual applications The Court may receive applications from any person, nongovernmental organisation or group of individuals claiming to be the victim of a violation by one of the High Contracting Parties of the rights set forth in the Convention or the Protocols thereto. The High Contracting Parties undertake not to hinder in any way the effective exercise of this right.

(3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR Protocol No. 9 to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms Rome, 6.XI.1990 Article 44 of the Convention shall read as follows: "Only the High Contracting Parties, the Commission, and persons, non-governmental organisations or groups of individuals having submitted a petition under Article 25 shall have the right to bring a case before the Court." Article 45 of the Convention shall read as follows: "The jurisdiction of the Court shall extend to all cases concerning the interpretation and application of the present Convention which are referred to it in accordance with Article 48."

(3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR Article 48 of the Convention shall read as follows: "1The following may refer a case to the Court, provided that the High Contracting Party concerned, if there is only one, or the High Contracting Parties concerned, if there is more than one, are subject to the compulsory jurisdiction of the Court or, failing that, with the consent of the High Contracting Party concerned, if there is only one, or of the High Contracting Parties concerned if there is more than one: a the Commission; ba High Contracting Party whose national is alleged to be a victim; ca High Contracting Party which referred the case to the Commission; da High Contracting Party against which the complaint has been lodged; e the person, non-governmental organisation or group of individuals having lodged the complaint with the Commission. 2If a case is referred to the Court only in accordance with paragraph 1.e, it shall first be submitted to a panel composed of three members of the Court. There shall sit as an ex officio member of the panel the judge elected in respect of the High Contracting Party against which the complaint has been lodged, or, if there is none, a person of its choice who shall sit in the capacity of judge. If the complaint has been lodged against more than one High Contracting Party, the size of the panel shall be increased accordingly. If the case does not raise a serious question affecting the interpretation or application of the Convention and does not for any other reason warrant consideration by the Court, the panel may, by a unanimous vote, decide that it shall not be considered by the Court. In that event, the Committee of Ministers shall decide, in accordance with the provisions of Article 32, whether there has been a violation of the Convention."

(3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR Protocol No. 11 to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, restructuring the control machinery established thereby Strasbourg, 11.V.1994 Article 26 Plenary Court The plenary Court shall: aelect its President and one or two Vice-Presidents for a period of three years; they may be re-elected; bset up Chambers, constituted for a fixed period of time; celect the Presidents of the Chambers of the Court; they may be re-elected; dadopt the rules of the Court; and eelect the Registrar and one or more Deputy Registrars.

(3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR Article 27 Committees, Chambers and Grand Chamber 1To consider cases brought before it, the Court shall sit in committees of three judges, in Chambers of seven judges and in a Grand Chamber of seventeen judges. The Court s Chambers shall set up committees for a fixed period of time. 2There shall sit as an ex officio member of the Chamber and the Grand Chamber the judge elected in respect of the State Party concerned or, if there is none or if he is unable to sit, a person of its choice who shall sit in the capacity of judge. 3The Grand Chamber shall also include the President of the Court, the Vice-Presidents, the Presidents of the Chambers and other judges chosen in accordance with the rules of the Court. When a case is referred to the Grand Chamber under Article 43, no judge from the Chamber which rendered the judgment shall sit in the Grand Chamber, with the exception of the President of the Chamber and the judge who sat in respect of the State Party concerned.

(3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR Protocol No. 14 to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, amending the control system of the Convention Strasbourg, 13.V.2004 Article 26 Single-judge formation, committees, Chambers and Grand Chamber 1To consider cases brought before it, the Court shall sit in a single-judge formation, in committees of three judges, in Chambers of seven judges and in a Grand Chamber of seventeen judges. The Court s Chambers shall set up committees for a fixed period of time. 2At the request of the plenary Court, the Committee of Ministers may, by a unanimous decision and for a fixed period, reduce to five the number of judges of the Chambers. 3When sitting as a single judge, a judge shall not examine any application against the High Contracting Party in respect of which that judge has been elected. 4There shall sit as an ex officio member of the Chamber and the Grand Chamber the judge elected in respect of the High Contracting Party concerned. If there is none or if that judge is unable to sit, a person chosen by the President of the Court from a list submitted in advance by that Party shall sit in the capacity of judge. 5The Grand Chamber shall also include the President of the Court, the Vice-Presidents, the Presidents of the Chambers and other judges chosen in accordance with the rules of the Court. When a case is referred to the Grand Chamber under Article 43, no judge from the Chamber which rendered the judgment shall sit in the Grand Chamber, with the exception of the President of the Chamber and the judge who sat in respect of the High Contracting Party concerned.

(3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR [T]he extent to which a non-governmental organization can invoke such a right must be determined in the light of the specific nature of this right. It is true that under Article 9 of the Convention a church is capable of possessing and exercising the right to freedom of religion in its own capacity as a representative of its members and the entire functioning of churches depends on respect for this right. However, unlike Article 9, Article 8 of the Convention has more an individual than a collective character( ). ECmHR, Church of Scientology of Paris v. France, application no. 19509/92, 09 January 1995.

(3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR Original intention of authors of the ECHR Dominant approach Complaint by: State Authors thought states should take the main initiative WWII had an impact on groups (Jews, Gays, Gypsies); minorities were granted a right to submit a complaint as a group. Goal was to allows civil society/human rights organizations to submit a complaint Inter-State complaints seldom used. About 20 so far, vis- -vis 22000 individual complaints. The court has denied groups as group a claim right. Individuals can bundle their complaints, but have to demonstrate individual harm each. Group Legal person Legal persons are allowed to complain with respect to a number of rights, such as the freedom of religion or the freedom of speech, but the Court has been very hesitant to allow legal persons to submit a complaint. Natural persons are responsible for the fast majority of complaints. Natural person Many countries were very hesitant to allow natural persons to complaint and made reservations

(3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR Original intention of authors of the ECHR Dominant approach Negative duty of the state Positive duty of the state Negative right/freedom of the individual Positive right/freedom of the individual General interests/abuse of power Individual interests/development of personality (almost everything that affects a personal interest will fall under the scope of Article 8 ECHR) Societal/group harm Individual harm (almost all complaints in which no personal harm can be demonstrated will be rejected by the ECtHR)

(3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR Insofar as the applicant complains in general of the legislative situation, the Commission recalls that it must confine itself to an examination of the concrete case before it and may not review the aforesaid law in abstracto. The Commission therefore may only examine the applicant's complaints insofar as the system of which he complains has been applied against him. ECtHR, Lawlor v. The United Kingdom, application no. 12763/87, 14 July 1988.

(3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR A priori claims It can be observed from the terms victim and violation and from the philosophy underlying the obligation to exhaust domestic remedies provided for in Article 26 that in the system for the protection of human rights conceived by the authors of the Convention, the exercise of the right of individual petition cannot be used to prevent a potential violation of the Convention: in theory, the organs designated by Article 19 to ensure the observance of the engagements undertaken by the Contracting Parties in the Convention cannot examine - or, if applicable, find a violation other than a posteriori, once that violation has occurred. Similarly, the award of just satisfaction, i.e. compensation, under Article 50 of the Convention is limited to cases in which the internal law allows only partial reparation to be made, not for the violation itself, but for the consequences of the decision or measure in question which has been held to breach the obligations laid down in the Convention. ECmHR, Tauira and others v. France, application no. 28204/95, 04 December 1995.

(3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR Hypothetical claim

(3) Complaint procedure: Dominant approach by the ECtHR The Court reiterates in that connection that the Convention does not allow an actio popularis but requires as a condition for exercise of the right of individual petition that an applicant must be able to claim on arguable grounds that he himself has been a direct or indirect victim of a violation of the Convention resulting from an act or omission which can be attributed to a Contracting State. ECtHR, Asselbourg and 78 others and Greenpeace Association-Luxembourg v. Luxembourg, application no. 29121/95, 29 June 1999.

(4) Complaint procedure: Recent developments Original intention of authors of the ECHR Dominant approach Latent new approach Complai nt by: State Authors thought states should take the main initiative Inter-State complaints seldom used. About 20 so far, vis- -vis 22000 individual complaints. Still very few inter-state complaints Group WWII had an impact on groups (Jews, Gays, Gypsies); minorities were granted a right to submit a complaint as a group. The court has denied groups as group a claim right. Individuals can bundle their complaints, but have to demonstrate individual harm each. More focus on group interests, though the ECtHR still not accepts groups invoking a right as a group Legal person Goal was to allows civil society/human rights organizations to submit a complaint Legal persons are allowed to complain with respect to a number of rights, such as the freedom of religion or the freedom of speech, but the Court has been very hesitant to allow legal persons to submit a complaint. The ECtHR does allow legal persons to invoke the right to privacy, both to protect their own interests and to protect societal interests, though the number of cases is still relatively small. Natural person Many countries were very hesitant to allow natural persons to complaint and made reservations Natural persons are responsible for the fast majority of complaints. Still the majority of the cases.

(4) Complaint procedure: Recent developments In Chappell v. the United Kingdom, the Court considered that a search conducted at a private individual's home which was also the registered office of a company run by him had amounted to interference with his right to respect for his home within the meaning of Article 8 of the Convention. The Court reiterates that the Convention is a living instrument which must be interpreted in the light of present day conditions. [] Building on its dynamic interpretation of the Convention, the Court considers that the time has come to hold that in certain circumstances the rights guaranteed by Article 8 of the Convention may be construed as including the right to respect for a company's registered office, branches or other business premises. ECtHR, Stes Colas Est and others v. France, appl.no. 37971/97, 16 April 2002, 40-41.

(4) Complaint procedure: Recent developments Exceptions Zakharov v. Russia (2015) Centrum F r R ttvisa v. Sweden (2018) Big Brother Watch and others v. the United Kingdom (2019)

(4) Complaint procedure: Recent developments [T]he Court accepts that an applicant can claim to be the victim of a violation occasioned by the mere existence of secret surveillance measures, or legislation permitting secret surveillance measures, if the following conditions are satisfied. Firstly, the Court will take into account the scope of the legislation permitting secret surveillance measures by examining whether the applicant can possibly be affected by it, either because he or she belongs to a group of persons targeted by the contested legislation or because the legislation directly affects all users of communication services by instituting a system where any person can have his or her communications intercepted. Secondly, the Court will take into account the availability of remedies at the national level and will adjust the degree of scrutiny depending on the effectiveness of such remedies. As the Court underlined in Kennedy, where the domestic system does not afford an effective remedy to the person who suspects that he or she was subjected to secret surveillance, widespread suspicion and concern among the general public that secret surveillance powers are being abused cannot be said to be unjustified.

(4) Complaint procedure: Recent developments In such circumstances the menace of surveillance can be claimed in itself to restrict free communication through the postal and telecommunication services, thereby constituting for all users or potential users a direct interference with the right guaranteed by Article 8. There is therefore a greater need for scrutiny by the Court and an exception to the rule, which denies individuals the right to challenge a law in abstracto, is justified. In such cases the individual does not need to demonstrate the existence of any risk that secret surveillance measures were applied to her. By contrast, if the national system provides for effective remedies, a widespread suspicion of abuse is more difficult to justify. In such cases, the individual may claim to be a victim of a violation occasioned by the mere existence of secret measures or of legislation permitting secret measures only if he is able to show that, due to his personal situation, he is potentially at risk of being subjected to such measures.