Colonial Medicine in South Asia: Impact on Healthcare Practices

Explore the evolution of colonial medicine in South Asia from the 17th to 20th century, focusing on the influence of European powers, the shift towards Western medical practices, the role of indigenous medical practitioners, and the impact on public health initiatives. Discover the changing dynamics between British and Indian physicians, the rise of traditional medicine, and the challenges faced by Indian medical professionals. Gain insights into the growth of hospitals, the promotion of European medicine superiority, and the complexities of healthcare accessibility in colonial India.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

COLONIAL MEDICINE IN SOUTH ASIA BY IZMAAND MARK

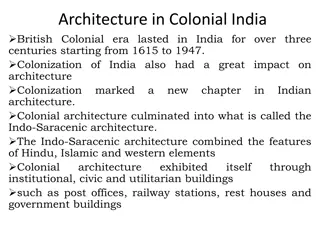

PRATIK CHAKRABARTI, MEDICINE AND EMPIRE, 1600- 1960 (BASINGSTOKE, 2014), CH.6: WESTERN MEDICINE IN COLONIAL INDIA, PP.101-121. Since the 17thC the EEIC established a no of permanent and semi permanent hospitals. Due to continuous warfare in India between European powers and Indian rulers, the EEIC created makeshift hospitals for soldiers. EEIC increasing dominance and territory in India was followed by the expansion of hospitals. Shift with the establishment of the Medical Department in 1786, run by army officers. Drs could no longer use diverse medicines and practices. More dependent on European medicines and the role of indigenous medical practitioners was reduced. Increasing monopoly of medical dispensaries by the EEIC with European instead of indigenous drugs. 19thC colonial medical colleges attached to hospitals were used to medically train Indians. Intention to produce more medical assistants and to encourage them to view British medicine as superior. Growth of public health for indigenous people not just Europeans in the mid 19thC. 18thC colonial port towns were still divided into white and black towns in the 19thC impacting the success of public health measures. 2 major public health episodes: Bombay plague outbreak 1896-7 and smallpox vaccinations. Late 19thc made smallpox vaccinations compulsory, shows how they wanted to establish a medical monopoly . Late 19thC, Germ theory leading to bacteriological labs and prophylactic vaccinations e.g cholera, plague, typhoid and rabies. India became a popular place for bacteriological experimentation and vaccination campaigns. Most of the historiography has focused on urban public health and up until WW1, less research on 1920-1950. More research could be done on class and colonial public health. Need for nuance, the colonial state wasn t monolithic and wasn t solely responsible/ influential over public health e.g influence of Indian elites. Late 19thC, rise of Indian nationalism leading to two main changes in colonial medicine: rise of traditional medicine and the growing competition and rivalry between British and Indian physicians. Difficult for Indian Drs to join the IMS (Indian Medical Service) and get the best jobs. Exams only held in Britain and their medical degrees were often not seen as equivalent to British ones. 1913 Indians were 5% of the IMS, 1921 6.25%. Created their own associations. LT effects of colonialism , hospitals tend to be in the 19thC main colonial cities e.g Bombay, Madras, Calcutta. Medical care is still more focused on the cities. As the colonization of India progressed, medicine changed from eclectic exchanges in costal regions to being part of colonial administration and hegemony. (pg 117)

MARK HARRISON, MEDICINE AND COLONIALISM IN SOUTH ASIA SINCE 1500 , IN MARK JACKSON (ED.), OXFORD HANDBOOK OF THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE (OXFORD, 2011), PP.285-301 Early 19thC somewhat respect for Indian medical treatments disappearing ,can be linked to more imperial governance. Indian medical traditions did not entirely disappear during colonialism. State sometimes recognizing their cultural significance by using traditional practitioners during epidemics. Was some fusion with traditional medical practitioners also gaining Western medical knowledge and training.Western and traditional medicines were being mass produced and mass marketed before independence. Mid Victorian era sanitary reform became more important, remained the official narrative for British rule that imperialism meant sanitary progress. BUT colonial public health prioritized Europeans and key parts of Indian society e.g the army. Most hospitals and dispensaries for the poor and for women as well as smallpox vaccinations were intended to civilize Indian people. Also showing themselves as better than indifferent Indian elites. Mid 19thC many elite Indians saw hospitals and dispensaries as ways to enhance their community standing. Over time hospitals became more popular and by the 20thC too many people wanted hospital treatment. Initially Indians were selective about what services they used. Growth in hospital use more among men than women. Difficult to persuade high caste Hindus and Muslim for their women to enter female establishments, even with all female staff. In remote areas missionaries were often the only Western medical institutions. Since the late 1980s many historians have commented on medicine s use as a tool of social control and its hegemonic role in establishing the dominance of Western culture. David Arnold can reasonably be said to have inaugurated this trend, blending together insights from Foucault and Gramsci. Since then, scholarship has highlighted the medical elements within racial theories, for example, and the role of medical institutions in expressing and consolidating colonial power. (pg 293)

SAURABH MISHRA, 'INCARCERATION AND RESISTANCE IN A RED SEA LAZARETTO, 1880-1930' IN ALISON BASHFORD (ED.) QUARANTINE: LOCAL AND GLOBAL HISTORIES (BASINGSTOKE, 2016). Focuses on the different kinds of resistance from Indian Hajjis that were medically inspected and sometimes quarantined on the Yemeni island Kamaran. How this impacted their experiences. If infected they could be held for at least 10 days, could be longer if the cholera came back. Indian government presented themselves as pro-Hajj, fear of interfering that would lead to uprisings. Why they sometimes challenged, subverted or ignored measures from other countries. Wealthier pilgrims were treated better by officials, can see this in the better treatment of women from respectable families compared to poorer women. Were able to bribe their way out of medical procedures and get supplies. Poorer pilgrims from South Asia being viewed as especially diseased, dangerous. Their awareness of how they were viewed. quarantine officials see Indian Hajjis as cholera personified. Camps were so crowded that pilgrims couldn t be fully controlled e.g non payment of poorer Hajjis became a norm. Cholera cases were actively hidden. Men and women were meant to be separated but this was rarely enforced, fear of strong reactions. Stowaways on ships, those supported by Islamic charities and waiting for the Indian government to pay to repatriate them. The only circumstances in which both poor and prosperous pilgrims could unite, though, was when the aggravation caused by medical measures was simply too much to bear or when there was a distinct possibility of missing the Hajj season altogether. (pg 65)

DAVID ARNOLD, COLONIZING THE BODY: STATE MEDICINE AND EPIDEMIC DISEASE IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY INDIA (1993), 'CH. 5: PLAGUE: ASSAULT ON THE BODY,' PP.200-239 1896-97 saw Bombay s municipal commissioner gain powers regarding the ability to hospitalise and segregate suspected plague cases, contrasting the prior actions of the government and municipal authorities. This was partly caused by international pressure, with other Western powers threatening to embargo India if nothing was done. The Indian and English press in India criticised the initial slow response to the plague outbreak by the government, as well as how forced hospitalisation and segregation of plague cases was carried out, such as the separation of families, and in particular women. Various rumours spread regarding the plague epidemic, including fears that doctors and hospital staff were poisoning Indians, fears regarding a plague vaccination being made compulsory, and the cutting up of bodies. These fears demonstrated the suspicion that Indians had of the government s measures. The government took advantage of the plague epidemic by dismantling an experimental council in Pune which allowed more control of the city, including its sanitary and medical service. However, in 1898-99 the government offered some concessions regarding its policies in dealing with the plague, such as admitting the segregation and hospitalisation measures (as well as the use of force more generally) proved to be counterproductive. Quotation: The scale and violence of public reaction caused the administration to doubt the political wisdom of persisting with such unpopular measures and brought about a dramatic shift in policy, with senior medical advisers supporting the view that only more conciliatory measures were practical, even though the costs in terms of plague deaths would inevitably be great (pps. 236-37).

SHELDON WATTS, FROM RAPID CHANGE TO STASIS: OFFICIAL RESPONSES TO CHOLERA IN BRITISH-RULED INDIA AND EGYPT: 1860 TO C.1921 , JOURNAL OF WORLD HISTORY, 12 (2001), 321-74. In 1868 the UK government reversed its policy of successful intervention in cholera epidemics back to a more old-school idea, where it was thought that nothing could be done to stop the spread of cholera. Prior to 1868, there were indications that British physicians had accepted the notion that cholera was not just a local disease, but one that was highly contagious meaning that interventionist policies, such as quarantine, would be effective. At the international sanitary conference (in Istanbul) in 1866, Leith (British sanitary commissioner from the Presidency of Bombay) recorded that cholera was accepted as being caused by poison, making it contagious, with interventions such as quarantining of ships from places with cholera epidemics recommended. Financial incentives contributed to the UK government s decision to reverse its policy on cholera; if the policy continued, ships carrying key raw materials for England s factories would be quarantined, losing money for England s elites who invested. Sheldon Watt argues that prior historiography have overlooked this reversal of cholera policy in India, instead seeing a continuous policy throughout. Quotation: In the context of official thinking in the summer of 1868, it was expected that in a few months many of these ships would be passing through the Suez Canal. Scheduled to open in November 1869, the new waterway would cut the distance between Bombay and London almost precisely in half: in the calculating world of commerce, time was money (p. 350).

QUESTIONS 1. How influential were modern theories of disease in developing policies around disease epidemics in colonial India? 2. How did social class and wealth impact the treatment and agency of Indian patients and physicians?

![READ⚡[PDF]✔ Emerging Space Powers: The New Space Programs of Asia, the Middle Ea](/thumb/21554/read-pdf-emerging-space-powers-the-new-space-programs-of-asia-the-middle-ea.jpg)