Comparative Study on Postgraduate Completion Rates

This presentation delves into the statistical data on time-to-completion for postgraduate students in South Africa from 2000 to 2005. It explores completion rates for Masters and Doctoral students, demographic differences, and factors affecting degree completion times.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

What makes a good Postgraduate student?

A good PG student. This presentation contains extracts from studies conducted to obtain comparative statistical data on throughput rates of postgraduates in South Africa CHE/CREST report (2009) Postgraduate Studies in South Africa: A Statistical Profile ASSAf report (2009) The PhD Report: An evidenced based study on how to meet the demands for high-level skills in an emerging economy Both of these texts are readily available online and on our learning site.

Completion rates: time to degree How long does the average Masters and Doctoral student take to complete his or her degree and has this situation changed between 2000 and 2005?

Completion rates Masters Doctoral 2000 2005 2000 2005 Mean N 2.9 Mean N 2.9 Mean N 4.8 Mean N 4.9 Nat & Agri Sciences Eng & App Tech Sciences Health Sciences Humanities Social sciences All fields 704 1 119 194 281 2.9 428 3.2 635 5.0 62 4.5 75 3.6 2.4 3.0 3.0 748 995 3 020 2.9 5 795 2.9 3.5 2.6 965 1 408 4.2 3 869 4.4 7 881 4.6 4.8 103 140 216 719 4.5 5.0 4.8 4.7 155 224 358 1 093

Time-to-degree: demographic differences No differences between male and female Masters students in 2000 or 2005 in the time taken to graduate. At the Doctoral level, female students completed their degrees slightly faster in 2000 compared with male students (4.4 years compared to 4.7). However, by 2008, these differences had disappeared, with both groups taking equally long (4.7 years). With regard to race, small differences for both qualifications and years were recorded. However, none of these differences suggests any major effect.

Time-to-degree: demographic differences Differences in age are strongly correlated with differences in completion rates. Not surprisingly older students take significantly longer to complete their degrees and this effect is more pronounced at the Doctoral level.

TIME-TO-DEGREE: DEMOGRAPHIC DIFFERENCES Masters Doctoral 2000 2005 2000 2005 Mean N 2.4 3.4 3.3 3.2 5.0 3.0 Mean N Mean N Mean N 3.5 4.7 4.9 5.3 5.5 4.7 <30 30 39 40 49 50 59 60 and older TOTAL 1 930 2.4 2 063 3.1 847 189 28 5 047 2.9 2 945 3.7 3 091 4.5 1 420 5.0 358 42 7 856 4.6 89 251 171 62 15 588 139 443 321 150 40 1 093 3.4 3.6 3.5 5.7 5.1

Gender Female students constitute slightly more than 50% of all Honours enrolments, but less than half at the Masters (46% in 2005) and Doctoral (40% in 2005) levels. Female students show increased representation in most fields (except for the Natural and Agricultural Sciences). Female graduates constitute significant proportions of the graduates in the Social Sciences. In all other fields and for both Masters and Doctoral degrees, female graduates are vastly in the minority.

Race There was a steady increase between 2000 and 2005 in the proportion of Black first enrolments at all levels: Honours: from 47% to 57% Masters: from 57% to 63% Doctoral: from 47% to 59%.

Race The proportion of African graduates also increased significantly between 2000 and 2005 at all levels, even though white graduates still constitute the largest single group of graduates at the Masters and Doctoral levels. African Doctoral graduates were increasingly represented in all fields between 2000 and 2005, particularly in the Natural and Agricultural Sciences (34% in 2005), while the share of White Doctoral graduates declined in all fields over the same period.

Age There was little difference in the age of students for Masters first enrolments in the under-30s between 2000 and 2005 (with 41% and 45%, respectively). However, Doctoral first enrolments under 30 decreased, comprising 28% and 21% respectively in 2000 and 2005.

Age One of the most striking findings concerns the changing mean age of postgraduate students in South Africa over the past few years. The mean age of Honours students increased significantly from 27 to 30 by 2005 Most Masters students now graduate at age 34 Most Doctoral students at age 40.

Age (continued) First, many Masters and Doctoral students typically interrupt their studies after having completed their Bachelors and Honours degree to enter the job market and then take up Masters studies later on. This interruption in studies, probably due to lack of financial resources, would invariably impact on their preparedness for advanced studies and might lead them to take longer to complete such studies.

Age Second, and more importantly, Doctoral students who enter into a career of academic scholarship or science potentially become productive quite late in their careers. There is a well-established correlation between having a Doctoral degree and publication productivity. Against a background of an ageing academic and scientific cohort, it is imperative that our Doctoral graduates start publishing as early on in their careers as possible.

What accounts for student attrition? Finding 16 (ASSAf report): Risk factors for non-completion (attrition) of doctoral candidates in South Africa are reported as: the age of the student at time on enrolment, coupled with professional and family commitments; inadequate socialisation experiences; poor student-supervisor relationships; insufficient funding.

Barriers to increasing productivity of doctoral programmes Finding 22 (ASSAf report): The primary barriers to increasing the productivity of PhD programmes at South African higher education institutions are: financial constraints; the quality of incoming students and blockages in the graduate and postgraduate pipeline; limited supervisory capacity; and certain government rules and procedures.

Pile-up effect Pile-up to refer to the state of affairs where students remain enrolled for their degree much longer than expected . When the number of recurring students becomes too large, this inevitably puts strain on the resources and affects the efficiency of the postgraduate system in general as its leads to increasingly larger numbers of students who need supervision.

Pile-up effect. Two indicators used to measure this pile-up effect: Ongoing enrolments as a percentage of total enrolments, and Graduates as a percentage of ongoing enrolments. When there is an increase in the value of the first indicator, it shows that more students are remaining, or piling up , in the system, while a decrease in the value of the second indicator means the system is producing fewer graduates.

Pile-up effect. The proportion of ongoing enrolments as a share of total enrolments has been increasing for both Masters and Doctoral students. Nearly two out of five (37%) of all enrolled Masters students in the system and three out of five (59%) of all enrolled Doctoral students in 2005 were historical enrolments. In addition, the proportion of Masters students graduating as a proportion of total enrolments remained the same (1 out of 5), but the situation for Doctoral students deteriorated from 14% in 2000 to 12% in 2005.

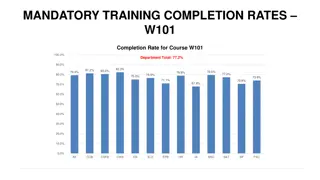

Pile-up effect Masters (headcount) First enrolment (x) Graduates (y) Ongoing enrolment (z) 9 556 Total enrolment (x+y+z) Indicators Ongoing enrolment as % of total enrolments (z(x+y+z))* 100 Graduates as % of total enrolments (y/(x+y+z))*100 2000 14 162 5 795 2001 15 888 6 426 9 642 31 956 2002 18 062 6 871 11 648 36 581 2003 19 352 7 396 13 091 39 839 2004 18 279 7 536 14 671 40 486 2005 17 398 7 881 15 105 40 384 29 9513 32% 30% 32% 33% 36% 37% 20% 20% 19% 19% 19% 19%

Conclusions? Think about these questions: What can we conclude from this presentation? What are the implications of these findings? What recommendations can you make as a result?

What is a good doctoral student? The statistics in this presentation present a picture of the reality of who our PG students are in terms of demographics and how long they take to complete. What factors do you or your dept. consider when selecting PG students? How do you think processes of student selection and supervision can contribute to: Equitable access Better retention and throughput What factors do you think most impact on student success at PG level?