Effective Grant Writing for Successful Research Funding

Learn the essential steps in grant writing for successful research funding. Discover how grants can support graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and researchers in the sciences. Plan your project effectively, conduct preliminary studies, and present compelling proposals to secure funding for your research endeavors.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

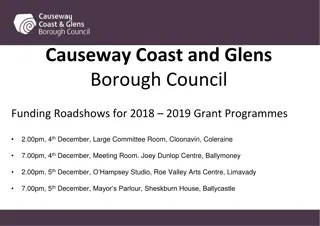

GRANT WRITING A GRADUATE WORKSHOP BY THE AWC

GRANT WRITING: INTRODUCTION Can allow researchers to delegate responsibilities to others (e.g., testing participants, coding data) Help support graduate students and postdoctoral fellows Grants provide funds to conduct research Can be critical for promotion and tenure decisions Can provide researchers with a summer salary

GRANT WRITING IN THE SCIENCES: INTRODUCTION To be competitive for funding, researchers must demonstrate that their project will make significant contributions to the field and has a high likelihood of success. Grant proposals typically describe in detail how the grant funds will be used, what the funds will allow the researcher to accomplish, and who will undertake the research activities. They are generally written in the following stages: Plan your project Locate funding opportunities Determine funder's requirements Write your grant proposal

PLAN YOUR PROJECT Before writing, plan your project timeline and objectives. Questions to ask include: What are the unique contributions this project is making to your field? What do you seek to achieve through your research? What are the major steps to project completion? Who will be involved in the project? Why is my project important and how is it different from others? What resources do I need? What type of grant do I need? Who can provide this type of funding? Why should they fund me?

PLAN YOUR PROJECT It is common to conduct a preliminary, or pilot, study to establish the feasibility of their project. A preliminary study is generally a smaller- scale version of the experiment that: Provides the opportunity to test methods, equipment, and other aspects of a project before beginning it officially Allows researchers to address errors and adjust research methods in a lower-stakes environment Provides a basis from which to extrapolate logistical and financial estimates Importantly, these preliminary results can persuade funders of the viability of the project, as they demonstrate that the researcher can conduct the study and has already identified and addressed possible shortcomings of the proposed research.

PLAN YOUR PROJECT: DETERMINE GRANT The resources required for a project often determine the type of grant that is required. Several types of grants are available, including: Small project grants (for equipment, imaging costs) Personal fellowships (for salary costs, sometimes including project costs) Project grants (for a combination of salary and project costs) Program grants (for comprehensive project costs and salary for several staff members). Check which funding body offers to fund which type of project, because most grant streams are quite specific about what they will and will not fund, both in terms of subject matter as well as resources (equipment or staff costs).

PLAN YOUR PROJECT: LOCATE FUNDING Research grants come from a range of organizations, including: Universities Private foundations Corporations Especially common in the sciences, government agencies In this last category, common sources of funding are the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF). Universities often provide funds for their own faculty members, especially early- career researchers.

If you have never applied for a grant, it may be best to start small. Several local groups, smaller charities, etc. offer start-up funding (which is also called small project grants, seed funding, or junior grants). There may be small grants available specific to your career grade, such as start-up grants for clinical lecturers or young academics within 5 or 10 years of completing their doctorate. PLAN YOUR PROJECT These form a useful platform from which to gain pilot data, which can then be synthesized into a larger grant application. Getting a small grant is an accomplishment that indicates potential and is viewed favorably when applying for further funding.

To locate additional funding opportunities, consult with an experienced colleague or mentor for suggestions. You can also refer to www.grants.gov and its searchable database of government grants. As you research grant opportunities, consider the following: Can you meet all of the application requirements, including the deadlines? What specific information do the reviewers require? What are the most important things to include about yourself/your research team and your project? If you are an assistant faculty member, have you taken advantage of opportunities specifically targeted at young/early researchers? PLAN YOUR PROJECT

PLAN YOUR PROJECT: DETERMINE FUNDER S REQUIREMENTS Create a checklist of the funder s requirements. Most funders will ask for a variation on a few things: Cover letter Biosketch/Qualifications Specific aims Funding agency requirements vary widely so always follow the agency s instructions carefully, as violations of instructions can lead funders to reject applications without reviewing them further.

DETERMINE FUNDERS REQUIREMENTS: COVER LETTER Some agencies ask for a cover letter in which the investigator can request that reviewers with specific expertise evaluate the application. These letters can help the agency board or distribution committee know how your application would be best evaluated. The cover letter should be concise and professional. Some granting agencies first require a Letter of Inquiry (LOI) before inviting a full proposal. Others welcome phone calls or e-mails.

DETERMINE FUNDERS REQUIREMENTS: BIOSKETCH/QUALIFICATIONS The biosketch should describe the investigator(s) relevant credentials, including training and recent publications. This section provides evidence of the qualifications needed to successfully complete the proposed research and publish on the results. Biosketches resemble CVs, but include more narration/personal statements. NIH guidelines: Name Position title Education/Training Personal statement Positions, Scientific Appointments and Honors Contributions to Science Scholastic Performance

DETERMINE FUNDERS REQUIREMENTS: SPECIFIC AIMS The Specific Aims section covers the major points of the project. It also can serve as a framework for developing the rest of the proposal, and as a project summary that will refresh the reviewers memory before they score the proposal. Specific Aims are sometimes organized in four parts: General goal/significance Theoretical framework/model Hypotheses Tests of the hypotheses A common weakness of grant proposals is the failure to identify a hypothesis, a new idea that can be tested experimentally and results in a rigorous and focused project.

After you have located a funding opportunity, planned your project, and outlined your grant proposal, it s time to start writing. WRITING YOUR GRANT PROPOSAL You may want to first read a few sample grants to better understand the content, tone, and style of successful proposals. Sample grants are often available on the funder s site and include annotations about the proposals strengths and weaknesses.

INTRO TO GRANT WRITING It is important to follow the directions of the grantmaker. Grantmaker often requires: Cover letter Executive summary Problem statements/need description Work schedule Budget Qualifications Conclusions Appendices/supporting materials

GRANTMAKER INSTRUCTIONS Important because it helps the grantmaker read applications efficiently Specificity of content will not only vary by grantmaker, but also by proposal sections For example, a grantmaker may limit your application in general terms for background information on the contexts of your proposal: Please tell the grant committee in 2 to 3 pages about the support your institution or community will provide for your project if your proposal is granted the requested funds. Many grantmakers will not read past the point of your departure from the application rules, no matter how worthy the project is or how neat and well designed the application package looks. While there is no guaranteed way to win a grantmaker s funds, not following directions is a surefire way of losing your chances at getting any funds Not following directions indicates carelessness which is not a characteristic of a promising proposal

SPECIFICITY IN WRITING STYLE Some authors struggle with specificity because they do not want to claim an absolute. Claiming an absolute usually has to do with using absolute terms, such as: all, none, every, never, always, and the like. Alternatively, absolute language creeps into writing by way of generalizations. Generalizations can come from statements that do not use absolute language such as all but include terms that categorize people, places, things, or actions. Writing specifically does not have to be dry, but it needs to be clear. Grantmakers read many applications so they will embrace and appreciate your getting to the point. This means your proposal must specifically state your issue, and how you will employ the requested funds.

SPECIFICITY IN WRITING STYLE General term More specific term Very specific term Students aged twelve to fifteen Young students Middle school students Between 7PM and 10PM central time Night time After 7 PM Corn farmers with less than 50 square acres of farm land Farmers Corn farmers High school algebra teachers with more than 15 years of teaching experience Math teachers Algebra teachers Marital status Single Never been married

Conserve words that are doing double duty and avoid redundancies CLARITY IN WRITING For example: better improvements, unique, one-of-a- kind opportunity The entire math department,including the department head and new teachers, will fully participate in the support tutoring sessions.

WRITING YOUR GRANT PROPOSAL: KEY GUIDELINES Focus on 3 P s: Person: the person leading the project needs to have a strong curriculum vitae (CV) or background and clear potential to succeed, and to be applying appropriately for their career stage and aspirations. Project: should be novel, with high scientific merit and with clear aims and objectives as well as a realistic timeframe. It should address a fundamentally important research question (or takes steps towards this) Place: should be an institution that has a strong track record in research, with the appropriate expertise, recognised supervisors/trainers and facilities. Many projects include an element of training, whether specific methodological aspects or generic research skills, and so it should be clear what new skills you will learn and that the senior members of your team are in a position to provide this. The project and training environment should be able to provide a valuable research experience.

WRITING YOUR GRANT PROPOSAL: KEY GUIDELINES Professional grant writers use clear, specific language to focus the reader s attention, and to persuade the reader to fund their proposal. Writing process can become easier with practice and awareness of a few common missteps. Manuscript writing, characterized by theme-centered, expository, dispassionate prose of scholarly pursuit, is markedly different from successful grant writing. The latter is characterized by a project-centered approach and a persuasive, personal tone conducive to addressing the service goals of the sponsor. (Leak et al)

Address experts and non-experts: Each of the reviewers should understand your project on a first read, even if they lack expertise in your sub-field. Because funding agencies consider many applications and have a limited amount of grant money, they give preference to projects that have clear aims and methods. WRITING YOUR GRANT PROPOSAL: KEY GUIDELINES Therefore, explain terms that might be unfamiliar to an educated but non- expert audience and avoid excessive use of jargon. The most successful proposals are written for readers who are scientists but are unfamiliar with the particular article. The prose is kept simple, specialized words and abbreviations are avoided, and every page has at least one diagram or figure. A well-written proposal is written to communicate with all the reviewers, not just those with expertise in the field (Ogden and Goldberg 21). While you will likely need to employ specialized terminology in the research methods section in order to provide adequate detail, tailor your other sections to a wider audience. This ensures that all reviewers understand the significance of your proposed study.

Emphasize actions and major steps The steps involved in the research, and who will be completing them, need to be clear to your reviewers on a first read. To accomplish this, use active voice, which emphasizes who or what is doing the important action in the sentence. WRITING YOUR GRANT PROPOSAL: KEY GUIDELINES Use diagrams or other visuals Diagrams are useful to cut down on length and reduce verbiage, as well as illustrate complex relationships that may be difficult to clarify in writing alone. The most effective ones are understandable without the reviewer having to refer to the corresponding caption/legend. When incorporating diagrams, remember to follow the funder s formatting requirements.

Again, stick to grantwriters specifications, but a general outline is typically ordered this way: Case for need: contextualize and quantify the problem Summary: a succinct outline of your proposal WRITING YOUR GRANT PROPOSAL: GENERAL OUTLINE The aim of this project, in context Methodology Pilot data Budget

GENERAL OUTLINE: CASE FOR NEED What is the question that I am addressing? Why is this project needed? What previous literature is available? How important, or how big, is the problem? What type of study would be required in an ideal world to address this issue (the best design approach)? If your proposal were successfully funded and successful in answering its objectives, what would that mean in a wider context? What is needed to bring this project to a wider audience? What is being done by other groups?

What is the expected outcome, and what is the expected impact? GENERAL OUTLINE: SPECIFIC AIMS Individual projects rarely stand alone and should be portrayed within the wider context of your institution, career intensions, and scientific community. Weaker grants are more likely to be funded if the institution or researcher is particularly strong, and strong scientific applications may fail when there is perceived to be limited potential.

Most important section of your grant application All reviewers will read your specific aims page Should provide an overview of your entire application Reviewers need to come away with a sense of: What you plan to do Why it is important How you plan to do it Frame a problem that your reader will care about and then convince the reader that you have the right solution Create a clear flow of information that pulls the reviewer along Think about What information your reader needs Why they need to know it When they need to see it GENERAL OUTLINE: SPECIFIC AIMS

GENERAL OUTLINE: SPECIFIC AIMS

Creating a Conceptual Framework GENERAL OUTLINE: SPECIFIC AIMS

GENERAL OUTLINE: METHODOLOGY The methodology section gives a skeleton or framework of the task and the resources required. How will potential sources of scientific bias be dealt with? It should also include rigorous statistical analysis and an estimation of the power of the study e.g., how many participants will be needed to reach a conclusion with x% confidence? Involving a statistician could help with much more than a sample size, including study objectives and design, analyses and outcome. It is often at this stage that other relevant team members become necessary, including clinical trialists, epidemiologists, health economists and qualitative researchers.

It is difficult to justify funding a theoretical problem but much easier to convince someone when you have tested your theories and demonstrated proof of principle. GENERAL OUTLINE: PILOT DATA While a feasibility study answers the question can this study be done? a pilot study is a miniature version of the whole study to test whether all the components can all work together (recruitment, test, follow-up, etc.), and it is designed to iron out the logistical issues.

GENERAL OUTLINE: BUDGET Financing your project appropriately is essential. Consider the people who will be needed, as well as materials, equipment, space and time. Justify your inclusion of everyone and everything, including who is accountable for what. Funding bodies look for a mix of personnel with the right expertise and skills and a strong track record. Don t underestimate or exaggerate the team skills or cost of your project; ensure that everything you need to make the project succeed is either included in the grant or is clearly funded from elsewhere. Navigate any potential intellectual property issues, either new or conflicting, and include this in the budget. Discussing your project early with your finance manager or equivalent is extremely useful.

THE WRITING PROCESS: SUCCESSFULLY SUBMITTING YOUR GRANT Grant writing requires a significant investment of time for planning, writing, and revising. The below tips will help you submit your grant on deadline, and many apply to other types of academic writing. Schedule adequate time for writing and revision. Ask multiple readers to review your work. Make a grid or a spreadsheet with key deadlines for yourself and/or your team, and hold each other accountable to them. Develop a style sheet for your team that outlines agreed upon usage of terminology, acronyms, hyphenated compound adjectives, or other frequently used words or phrases. Write faithfully for a set amount of time each day. Schedule writing time for yourself and show up to it like a job; resist scheduling meetings or other commitments during this time. Ask a mentor who is knowledgeable about the field to review your writing. Submit your application early to avoid last-minute delays or technical problems with the online submission.

Unfortunately, very few proposals are funded initially (some NIH institutes, for example, fund less than 10% of submissions). Proposals rejected in the first round are often revised and resubmitted, so try to get feedback from the reviewers. Some funding bodies provide limited feedback and allow a limited number of repeated attempts at each stage it is worth knowing how many attempts you have in advance of your first one. The most important thing you can do is read the reviews carefully and revise your application accordingly and as quickly as possible. Did you anticipate the potential problems in the grant that the funding body identified? Did you show that you had recognized these and thought how they might be dealt with, if encountered? Several larger grant applications are now a two-stage process: an initial outline stage, and then a full application. It is strongly advised that you have written the full application by the time the outline deadline has arrived. WHAT NEXT?

There are several requirements for getting a project up and running other than successful funding: A sponsor (the organization accountable for the research) Ethical approval from a recognized body (to protect research participants) Local research and development approval or permission, local research networks, as well as other regulatory approvals (e.g., clinical trials, medicines) and honorary contracts for those involved. Applying for these may be just as time-consuming (if not more so) than the actual grant application process and should ideally be undertaken in parallel. Getting the grant is just the beginning of your research journey, and whilst you are enjoying the research, bear in mind that all grants are finite, with a clear end date, and you will need to justify the use of resources. WHAT NEXT?

Although the grant writing process may seem daunting, help is widely available, whether you are at the brainstorming or submission stage of the process. Your local research and development team, fellow scientists (especially those who sit on grant review panels), funding bodies and several Web sites are useful sources of guidance regarding where to start, and they might offer to review your proposals and give helpful feedback. CONCLUSION The earlier you start, the more detailed feedback you will get. The more time you allow yourself to have in responding to that feedback, the better your application will be.

THE ACADEMIC WRITING CENTER The Academic Writing Center is here to help you! We have tutors available, helpful handouts, other resources available from our website: uc.edu/awc. Individual tutoring isn t just for undergrads! There are graduate tutors who are excited to help you work through any of your writing assignments. Sign up using the schedule an appointment tab on the website. Email the AWC GA: bolingbe@ucmail.uc.edu The schedule for the remaining workshops this semester is posted at: www.uc.edu/learningcommons/writingcenter/grad.html

The purpose of this program is to assist early career/junior investigators in the preparation of their first R01 proposal to improve grantsmanship by promoting clarity of thought and logical presentation of a research proposal so as to have the greatest impact on fundability. https://med.uc.edu/research/recent Offers a workshop on How to construct a Specific Aims page Participants submit their Specific Aims page to be reviewed constructive feedback will be provided 2 to 3 candidates (per grant cycle) selected for one- on-one grant writing assistance will receive comprehensive proposal content edits and feedback from grant writer, Jen Veevers PhD Additional materials will be provided to each participant, including example sections of successful proposals For information, contact Brieanne Sheehan at sheehabe@uc.edu R CLUB GRANT PROGRAM

Research Development Workshop: Jen Veevers, UC COM/CCTST (provided by Gary Gudelsky) NIH Info on Biosketches Arthurs, Owen J. Think it through first: questions to consider in writing a successful grant application. Pediatric radiology vol. 44,12 (2014): 1507-11. doi:10.1007/s00247-014-3053-6 NIH Write Your Application Info Webpage REFERENCES NIH How to Apply Info Webpage Leak, Rehana K et al. Teaching Pharmacology Graduate Students how to Write an NIH Grant Application. American journal of pharmaceutical education vol. 79,9 (2015): 138. doi:10.5688/ajpe799138 Purdue OWL: Grant Writing in the Sciences UC Grant Writing Resources