English Constitutional History in the XVIII Century - Monarchy, Ministers, and Dilemmas

The XVIII century English constitutional history explores the dynamics between the monarchy, Parliament, and ministers, highlighting conflicts, the role of the King in choosing ministers, and the development of governmental structures. Discussing key monarchs like George III, the emergence of the Cabinet, and the challenges faced during the revolutionary settlement, this era laid the foundation for the parliamentary government of the XIX century.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

English Constitutional history The XVIII century constitution Prof. Marco Olivetti LUMSA Rome, October 18th, 2023

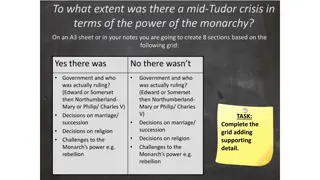

The constitutional dilemma of the revolutionary settlement The revolutionary settlement recognized the executive power to the King, who had to exercise it through its ministers , chosen and dismissed by him The legislative power was placed in Parliament, composed by the House of Commons, the House of Lords and the King The financial power (taxes and expenses), with a central role of the House of Commons How the right of the King to choose its ministers was to be reconciled with that of the House of Commons to refuse supply to ministers it did not trust ? (D. Marshall, p. 189) The risk of anachronism in interpreting the XVIII century constitution: seeing in it the embryo of the parliamentary government of the XIX century Two absent subjects of the XIX century constitution in the XVIII century: a national will expressed through elections and disciplined political parties

The Monarchy: the House of Hannover House of Hannover George I 1714-1727 (from 1917 Windsor) George V 1910-1936 George II 1727-1760 George III 1760-1820 (regency after 1810) George IV 1820-1830 William IV 1830-1837 Victoria 1837-1901 Edward VII 1901-1910 Edward VIII 1936 (abd.) George VI 1936-1952 Elizabeth II 1952-

Characters of the monarchy Foreign kings (George I and George II), with large interests in the Electorate of Hannover (entanglement with European wars) The first King barely spoke English and was rather distant from English common sense A Protestant monarchy and the Jacobite rebellions of 1715 and 1745 Conflicts between the King and the Prince of Wales under the first two reigns A true English king in 1760: George III

The King and his ministers The King was entitled to rule, not only to reign The King was free to choose his ministers and to dismiss them The freedom of choice of the King was actually limited by the availability of ministers willing to serve together and by the possibility of finding support in Parliament, specially when money was needed The ministers were appointed by the King as individuals not as a collective body (Privy Council or Cabinet) The Cabinet began to meet without the King The formal Chief of the government was the King himself Divided cabinets and dominant ministers o Prime ministers ? Individual and/or collective responsibility before the House of Commons?

The House of Lords Members of the Chambers were nobles who inherited the membership of the House together with their title The Bishops and archibishops of the Anglican Church were also members of the House There were Scottish representative peers, elected in Scotland The King could appoint new peers, usually with the right to transmit it to the heirs During the greater part of the century a large proportion of the ministers were members of the house of lords (D. Marshall, p. 52) As heads of great aristocratic families, some members had influence over elections for the House of Commons The bishops and the Scottish representative peers were subject to government s influence

The House of Commons 558 members (489 English, 24 Welsh, 45 Scottish) in 1714 Duration: 3 years, but after the Septennial Act (1716) 7 years, unless previously dissolved by the King Automatic dissolution six months after the accession of a new King: 1714, 1727, 1760 XVIII century elections: lack of a national competition The vote was public this allowed room for control by local magnates The franchise : very different at local level Influence on elections: the role of the great families at local level; government s influence through appointment to local and national offices dependent from the Government (patronage) Elections were dominated by local problems and public opinion was expressed only in some large constituencies Throughout the XVIII century no government never lost an election (Keir, p. 297) Independent members (the country gentlemen)

Composition of Parliament: parties The ultimate origin: Court v. Country, Stuarts v. the new Dynasty Whigs and Tories appear for the first time during the Exclusion crisis of 1679-1681 (the attempt of the Whigs to exclude from the succession the brother and heir of Charles II, James, duke of York, who was catholic) Negative meaning of the name: Whigs & Tories A) Whiggamores were Scottish Covenanting rebels and terrorists B) Tories were Irish papist outlaws, cattle-thieves and brigands Whig hegemony after 1688, but many cabinets were mixed The Whigs lead Britain to the victory in the War of the Spanish succession (1700-1713) but in the last four years of the reign of the Queen Ann the Tories were in power (Bolingbrook and Oxford) Whigs were the architects of the Hannover succession, while Tories were open to some form of Stuart restoration

Whigs and Tories in the XVIII century With the Hannover succession (George I, 1714), Whig hegemony was established Tories were identified with opposition not only to the single government in power but to the Dynasty and sometimes are identified with the Jacobites Although a Tory sentiment and single Tory personality subsisted, a Tory party actually disappeared in the central decades of the XVIII century and politics was divided mainly between various Whig factions Some great Whig families (large landowners) dominated English politics The great Whig Statesmen of the XVIII century: Walpole, Henry Pelham, Newcastle, Chatham

Majority and opposition English political doctrine in XVIII century regarded organized opposition as faction Political opposition to the King s minister was for some time structured around the Prince of Wales, the heir of the throne, who was in conflict with his father (1714-27; 1740-51) Parliament was divided in groups loyal to some personalities Many MPs were sensible to appointment to office for them or for their followers Yet argument (both the policy and parliamentary rhetoric) counted and the result of a vote in the House could not always been taken for granted The government in a given moment was composed of a coalition of leaders of some of the groups existing in Parliament When the King appointed his ministers, he had to consider the parliamentary situation and the ability of at least some of his ministers to manage parliament (manipulating some members and selling there the government s policies)

Prime ministers? In each Cabinet did actually exist one or two dominating ministers In some periods a minister was able to a) enjoy the confidence of the King, b) lead parliamentary decisions, c) direct and coordinate the action of this Cabinet colleagues The myth of Robert Walpole as the first Prime minister in English history (1721-1742) Other prime ministers : Henry Pelham, the duke of Newcastle, Rockingham, W. Pitt the younger

The social bases of the Constitution A small country (6 millions compared with the 18 of France), but a rising Great Power Marginalization of the losers of the previous century (catholics, jacobites, Ireland, Scotland) Absence of radical conflicts similar to those of the XVII century Social mobility, despite the leading role of aristocracy Trade, piracy and the birth of the first British colonial empire (1607-1783) A maritime power: North America, the Caribbeans, coastal areas in Africa, India, the Mediterranean Between war and peace: the war of the Spanish succession (1700-1713), the politics for peace under Walpole, the war of the Austrian succession (1740-48) and the Seven Years War (1756- 1763)

The myth of the English Constitution Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765): a mixed constitution the King in Parliament Montesquieu, L Esprit des lois (1748): the separation of power as an instrument to guarantee freedom Voltaire, Short Studies on English Topics with notes on the peopling of America De Lolme, La Constitution de l Angleterre, 1777 The English constitution as the alternative to absolutism prevailing in Continental Europe (France, Spain, Austria, Prussia, Russia ) also to enlightened absolutism (Frederik II of Prussia, Maria Theresa of Austria ) The English constitution as an ideal settlement because separation of powers is seen as an instrument to guarantee freedom The first wave of Export of the English constitution: the American colonies

Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, 1767 Herein consists the true excellence of the English government, that all parts of it form a mutual check upon each other. In the legislature, the people are a check upon the nobility and the nobility a check upon the people while the King is a check upon both, which preserves the executive power from encroachments. And this very executive power is again checked and kept within due bounds by the two Houses. Thus, every branch of our civil polity supports and is supported, regulates and is regulated, by the rest: for the two Houses, naturally drawing in two directions of opposite interest, and the prerogative in another still different from both, they mutually keep each other from exceeding their proper limits Like three distinct powers in mechanics, they jointly impel the machine of government in a direction different from what either, acting by itself, would have done a direction which constitutes the true line of the liberty and happiness of the country (p. 154-155)

Voltaire, Short studies on English Topics The English are the only people on earth who have been able to prescribe limits to the power of kings by resisting them, and who, by a series of struggles, have at length established that wise and happy form of government where the prince is all powerful to do good, and at the same time is restrained from committing evil; where the nobles are great without insolence or lordly power, and the people share in the government without confusion. The House of lords and the House of commons divide the legislative power under the King; but the Romans had no such balance. Their patricians and plebeians were continually at variance, without any intermediate power to reconcile them. The Roman senate, who were so unjustly, so criminally, formed as to exclude the plebeians from having any share in the affairs of government, could find no other artifice to effect their design than to employ them in foreign wars. They considered the people as wild beasts, whom they were to let loose upon their neighbors, for fear they should turn upon their masters. Thus the greatest defect in the government of the Romans was the means of making them conquerors; and, by being unhappy at home, they became masters of the world, till in the end their divisions sank them into slavery. The government of England, from its nature, can never attain to so exalted a pitch, nor can it ever have so fatal an end. It has not in view the splendid folly of making conquests, but only the prevention of their neighbors from conquering. The English are jealous not only of their own liberty, but even of that of other nations. The only reason of their quarrels with Louis XIV was on account of his ambition. It has not been without some difficulty that liberty has been established in England, and the idol of arbitrary power has been drowned in seas of blood; nevertheless, the English do not think they have purchased their laws at too high a price. Other nations have shed as much blood; but then the blood they spilled in defence of their liberty served only to enslave them the more .

Criticism of the Constitution General support for the Constitution as a guarantee for freedom The most common criticism dealt with influence and manipulation of MPs by the Government Patronage was seen as a form of corruption The request to exclude placemen from Parliament: rules of incompatibility between the position of MP and that of holder of an office under the Crown Ambiguity of the role of the King and of its ministers in relation to Parliament: the question of the parliamentary role in directing policy Later criticism: a Venetian oligarchy; the unrepresentative nature of the House of Commons

Ideas for reforms in the Constitution Parliamentary reform: reforming the system of election, reducing the role of pocket and rotten boroughs and giving more representation to the counties (later to new cities) Reducing the patronage and introducing rules of incompatibility Crewe s Act 1782 A new idea of party as a body of men united for promoting by their joint endavours the national interest upon some particular principle in which they are all agreed (Burke in Thoughts on the Causes of the present discontent, 1770) Proposals of Fox for annual elections Yet the French revolution and its excesses blocked the movement in favour of reform for 50 years, until 1832

A turning point: 1760 The accession of George III, the first truly English King ot the Hannover dynasty A young King playing an active role: manipulation of governments and instability Recover of stability after 1770 with Lord North s government The crisis generated by the American revolution (1774-1783) the defeat of England and the loss of the bulk of the first Colonial empire The constitutional crisis of 1783: a King s government against the House of Commons and the use of dissolution and of new elections to endow the government of parliamentary support A new party division: the younger Pitt from whig to new tory The consequences of the French revolution and the conservative turn

Interpretations of the accession of George III Tory interpretation While George II was in the grip of the Whig magnates, who had usurped many of the royal powers and made his active intervention in politics ineffectual, George III was not content to play a passive role and was determined to regain those powers which the revolutionary settlement had left him. Fight to the use of patronage as a form of corruption end to proscription towards the Tories choice of the ministers as individuals to serve the King

Interpretations of the accession of George III Whig interpretation of the central parts of the Victorian era George III s intervention in politics, manipulating government formation and his conflicts with the Whig leaders as a retrograde step towards arbitrary government An attempt by the monarch to stop the gradual evolution towards responsible government, in which the Cabinet is based on a majority in Parliament

Interpretations of the accession of George III Lewis Namier and his school The ambiguity of the revolutionary settlement XIX century responsible government did yet not exist in 1760 The picture of a King reduced to being a puppet in the hands of his ministers is not in accord with the facts of the closing years of George II s reign (D. Marshall, p. 313) A difference was the lack of a heir to the throne as a rallying point for opposition to the King s government policy

The constitutional crisis of 1780-4 The gravest of all constitutional crisis of the XVIII century, caused by the American War of Independence (Briggs, p. 76) Elections 1780: a slim majority for the government The fall of Lord North s Government (1782): an express vote of no-confidence in the House of Commons The Rockingham ministry and the peace of Paris with USA, Spain and France (1782) The Shelburne government (July 1782- Feb. 1783) Defeated on a motion of censure The coalition of the two enemies (Fox-North) under the presidency of the Duke of Portland A model of government based only on the parliamentary majority, denying to the King a participation to the choice of ministers and to the formulation of policy The King is obliged to accept the new Government

The constitutional crisis of 1780-4 After the appointment of the new government, opposition of the King to the Fox-North coalition The King authorizes lord Temple to say in public that those who will vote for the East India Company bill will not be regarded as his friends defeat of the bill in the House of Commons and of the Government The King dismisses Fox and North William Pitt the younger (24 years old) is appointed prime minister Various votes of the House of Commons against the new government The government does not resign and remains in office Dissolution of the House of commons The use of royal patronage in the 1784 general elections The opposition loses 100 seats, clear victory of the government s supporters

William Pitt the Younger A long premiership: 1783-1801 and 1804-1806 Pitt as a Whig for political origin, but pictured as a Tory by the opposition (Fox) 1783-1806: The implacable rivalry between Pitt and Fox (both died in 1806) Fox: defense of individual freedom (Whigs) vs. royal prerogative - residual powers of the King as the base of government (Tories) Foreign policy: Pitt and the anti-French coalition and the reluctance of Fox to fight against revolutionary France

The final decline and the demise of the XVIII century constitution After Pitt s death (1806): further fragmentation of the party system in various groups Lord Liverpool s long government (1812-1827) and its successors (Cannings, Goderich & Wellington: 1827-1830): a new toryism? After 1810: the regency and two weak kings (George IV and William IV) The new cleavage: pro and against political reform of the unrepresentative House of Commons Tory reforms: Repeal of the test and corporations act 1829 and Catholic Emancipation 1829 The representation of the people act, 1832

Suggested readings D. Marshall, Eighteen Century England, Longman, II ed., London, 1974 A. Briggs, The Age of Improvement 1783-1867, Longman, London, 1959 E.N. Williams, The Eighteenth Century Constitution. Documents and Commentaries, Cambridge Up, Cambridge, 1960 D.L. Keir, Constitutional History of Modern Britain from 1485 to 1937, IV ed., Black, London, 1950 C.L. Montesquieu, Spirit of the Laws, 1748, II part, XI book, VI chapter (La Constitution de l Angleterre) Voltaire, Philosophical Letters: https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/voltaire-the-works-of-voltaire- vol-xix-philosophical-letters