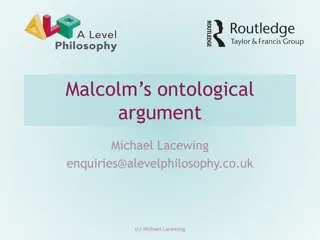

Exploring the Relationship Between God, Philosophy, and Descartes: Insights and Reflections

Delve into the intriguing connections between God, philosophy, and Descartes through discussions on thinking, praying, dancing, and the profound implications on metaphysics. Discover the intricate concepts of God's existence, Descartes' bridge of thought, and the complexities of theological reflections in philosophical discourse.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

God: Thinking, Praying, Dancing Philosophy Through the Year: God Stuart Jesson London Jesuit Centre

God: Descartes bridge The road that Descartes constructed back from the extreme point of the Doubt, and from the world merely of his first-personal mental existence which he hoped to have established in the cogito, essentially goes over a religious bridge. . . . .The collapse of the religious bridge has meant that his most profound and most long-lasting influence has not been in the direction of the religious metaphysics which he himself accepted. Rather, philosophy after Descartes was driven to search for alternative ways of getting back from the regions of skepticismand subjective idealism in which it was stranded when Cartesian enquiry lost the Cartesian road back. (Williams, 1978: 162) This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND

God: Thinking, Praying, Dancing Some tensions, connected to the relationship between God and philosophical argument and analysis: reason/revelation; reason/revelation; theory/practice; theory/practice; conceptual content/reasons for belief; conceptual content/reasons for belief; conceptual content/genealogy/function conceptual content/genealogy/function

Descartes idea of God But in a crucial way, the idea of God is somehow more fundamental than the awareness of our own subjectivity: . . . I clearly understand that there is more reality in an infinite substance than in a finite one, and hence that my perception of the infinite, that is God, is in some way prior to my is in some way prior to my perception of the finite perception of the finite, that is, myself. For how could I understand that I doubted or desired that is, lacked something and that I was not wholly perfect, unless there were in me some idea of a more perfect being which enabled me to recognize my own defects by comparison? (Descartes 1996: 31) So: does thinking begin with itself (Meditation 1); or with God (Meditation 3)? Can God be thought because we can think? Or, does thinking depend on God?

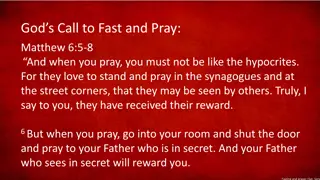

God: Thinking, Praying, Dancing In an essay on The onto-theo-logical constitution of metaphysics , Martin Heidegger reflected on the God of the philosophers , and in particular on Leibniz s conception of God as the causa sui (self-caused/causing): This is the right name for the god of philosophy. Man can neither pray nor sacrifice to this god. Before the causa sui, man can neither fall to his knees in awe nor can he play music and dance before this god. (Heidegger 1969: 72) But how, then, can God be thought But how, then, can God be thought as truly divine as truly divine? ?

Aquinas on the existence of God For Aquinas, we can never really know what we mean by the word God even though we can know that God exists: Once it is known that something exists, it remains to be investigated how it exists, in order that what it is may be known. But because it is not possible for us to know what God is, but rather what God is not, we cannot consider how God exists, but rather how God does not exist. (ST I, q3) So we can know that God is, we can know what God is not, but we cannot know what God is. Why is this? To answer, we have to look both at why we would need to talk about God in the first place .

The existence argument Aquinas arguments for the existence of God all have a similar shape: In general, Aquinas's Five Ways employ a simple pattern of argument. Each begins by drawing attention to some general feature of things known to us on the basis of experience. It is then suggested that none of these features can be accounted for in ordinary mundane terms, that we must move to a level of explanation which transcends that with which we are familiar transcends that with which we are familiar. (Davies 2009: 29) However, one line of thinking is particularly important for Aquinas; the one based on the idea of existence, or being .

The existence argument Aquinas therefore maintains that there is a first source of existence by which he means God. For, he adds, if the existence of everything depends on something which in turn depends for its existence on something else, the series of existing things will not be accounted for at all. There cannot be a never ending series of things caused to be and causing to be. If each cause of A's existence were itself in need of a cause of its existence, then no cause of A could exist, and A itself could not exist. Since A does exist, and does need a cause, it follows that not all of A's causes are in need of a cause. In other words, the need for causes of existence must come to an end: there must be a cause the existence of which is not itself in need of a cause which is not itself in need of a cause. Given that there are things in whose nature or essence existence is not included, there is something which produces their being, something which makes them to be though nothing makes it to be (Davies 2009: 33)

The existence argument 1) No contingent being exists by nature, but is caused to exist by something external to itself; Or: existence cannot be deduced from essence; Or: nothing is its own reason for existing. 2) If everything depended for its existence on something external, nothing would ever come to exist; 3) But there are contingent beings; 4) Therefore there must be something uncaused, which exists by nature. Or: there must be a source of all being, the essence of which is to exist Or: there must be that which is its own reason for existing; Or: there must be a necessary being 5) And this, we call God

Aquinas on the existence of God But this also means that we cannot expect to understand what God is, because we have no clear idea of what necessary existence means. God s existence is not self-evident to us, even though God s existence is necessary, in itself Hence I say that this proposition "God exists" is self-evident in itself because the predicate is identical with the subject: for God is his existence, as will later be made clear [3.4]. Yet since we do not know what God is, the proposition is not self-evident to us but rather must be demonstrated through what is more evident to us, even if less evident by nature, namely through God's effects. (Summa Theologiae I, q2, a2)

Conceptual content/genealogy/function Conceptual content/genealogy/function Two-world thinking in philosophy, according to Nietzsche: Pre-Socratics: appearances & reality Plato: sensible & intelligible change & permanence becoming & being Descartes: extended matter & thinking soul Kant: phenomenon & noumenon appearances & things-in-themselves nature and freedom

Conceptual content/genealogy/function Conceptual content/genealogy/function Two-world thinking in Christianity, according to Nietzsche: Spiritual vs physical? Heaven vs earth? Hebrew Bible/Israelite religion Chosen people vs. Gentiles (Jacob and Esau, etc.) Jesus Kingdom of God vs. the world St. Paul Sin/the flesh vs. life in Christ Christian orthodoxy Now vs. the age to come Heavenly powers vs. earthly powers Eternity vs. time

Conceptual content/genealogy/function Conceptual content/genealogy/function 2. We invented the concept purpose : in reality, purpose is absent . . . One is necessary, one is a piece of fate, one belongs to the whole, one is in the whole there is nothing which could judge, measure, compare, condemn our Being, for that would mean judging, measuring, comparing, condemning the whole . . . But there is nothing apart from the whole! That no one is made responsible any more, that a kind of Being cannot be traced back to a causa prima, that the world is no unity, either as sensorium or as mind , this alone is the great liberation this alone re- establishes the innocence of becoming . . . The concept God has been the greatest the greatest objection objection to existence so far . . . We deny God, we deny to existence so far . . . We deny God, we deny responsibility in God: responsibility in God: this this alone is how we redeem the world alone is how we redeem the world. (TI The Four Great Errors: 8/p. 473) The concept God has been

Philosophy Through the Year: God 1.God: Thinking, Praying, Dancing 2.Creation, Creator and Creatures 3.Simplicity and Perfection 4.Power, Freedom and Evil 5.Time, Eternity, Eschatology