Gallbladder Surgical Anatomy and Physiology Overview

Explore the detailed surgical anatomy and physiology of the gallbladder, including information on its structure, divisions, ducts, and their anatomical variations. Gain insights into cholelithiasis and cholecystitis.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Surgical Anatomy & Physiology Of Gallbladder Cholelithiasis & Cholecystitis DR.RAMDAS RAI PROF. & UNIT CHIEF YMCH

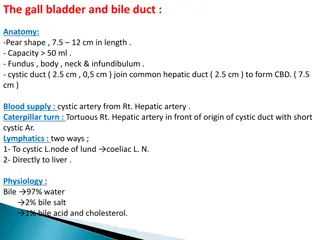

SURGICAL ANATOMY The gall bladder lies on the underside of the liver in the main liver scissura at the junction of the right and left lobes of the liver. The relationship of the gall bladder to the liver varies between being embedded within the liver substance to being suspended by a mesentry

It is a pear-shaped structure,7.512 cm long, with a normal capacity of about 25 30 mL. The anatomical divisions are a fundus, a body and a neck that terminates in a narrow infundibulum. The muscle fibres in the wall of the gall bladder are arranged in a criss-cross manner, being particularly well developed in its neck. The mucous membrane contains indentations of the mucosa that sink into the muscle coat; these are the crypts of Luschka.

The cystic duct is about 3 cm in length, but the length is variable. The lumen is usually 1 3 mm in diameter. The mucosa of the cystic duct is arranged in spiral folds known as the valves of Heister and the wall is surrounded by a sphincteric structure called the sphincter of L tkens . The cystic duct joins the supraduodenal segment of the common hepatic duct in 80 per cent of cases; however, the anatomy may vary and the junction may be much lower in the retroduodenal or even retropancreatic part of the bile duct.

The common hepatic duct is usually less than 2.5 cm long and is formed by the union of the right and left hepatic ducts. The common bile duct is about 7.5 cm long and formed by the junction of the cystic and common hepatic ducts. It is divided into four parts:

Supraduodenal portion. About 2.5 cm long, running in the free edge of the lesser omentum. Retroduodenal portion. Infraduodenal portion lies in a groove, but at times in a tunnel, on the posterior surface of the pancreas. Intraduodenal portion passes obliquely through the wall of the second part of the duodenum, where it is surrounded by the sphincter of Oddi, and terminates by opening on the summit of the ampulla of Vater.

The cystic artery, a branch of the right hepatic artery, usually arises behind the common hepatic duct. The most dangerous anomalies are where the hepatic artery takes a tortuous course on the front of the origin of the cystic duct , or the right hepatic artery is tortuous and the cystic artery short . The tortuosity is known as the caterpillar turn or Moynihan s hump . This variation is the cause of many problems during a difficult cholecystectomy with inflammation in the region of the cystic duct.

Lymphatics The lymphatic vessels of the gall bladder (subserosal and submucosal) drain into the cystic lymph node of Lund (the sentinel lymph node), which lies in the fork created by the junction of the cystic and common hepatic ducts. Efferent vessels from this lymph node go to the hilum of the liver, and to the coeliac lymph nodes. The subserosal lymphatic vessels of the gall bladder also connect with the subcapsular lymph channels of the liver, and this accounts for the frequent spread of carcinoma of the gall bladder to the liver.

Surgical physiology Bile is produced by the liver and stored in the gall bladder from which it is released into the duodenum. As it leaves the liver, it is composed of 97 per cent water, bile salts (cholic and cheno-deoxycholic acids, deoxycholic and lithocholic acids), phospholipids, cholesterol and bilirubin. The liver excretes bile at a rate estimated to be approximately 40 mL/hour. About 95 per cent of bile salts are reabsorbed in the terminal ileum (enterohepatic circulation).

FUNCTIONS OF THE GALL BLADDER The gall bladder is a reservoir for bile. During fasting, resistance to flow through the sphincter of Oddi is high, and bile excreted by the liver is diverted to the gall bladder. After feeding, the resistance to flow through the sphincter is reduced, the gall bladder contracts and the bile enters the duodenum. These motor responses of the biliary tract are in part effected by the hormone cholecystokinin.

The second function of the gall bladder is concentration of bile by active absorption of water, sodium chloride and bicarbonate by the mucous membrane of the gall bladder. The hepatic bile which enters the gall bladder becomes concentrated 5 10 times, with a corresponding increase in the proportion of bile salts, bile pigments, cholesterol and calcium

The third function of the gall bladder is the secretion of mucus approximately 20 mL is produced per day. With complete obstruction of the cystic duct in an otherwise healthy gall bladder, a mucocoele may develop as a result of ongoing mucus secretion by the gall bladder mucosa.

GALLSTONES (CHOLELITHIASIS) Gallstones are the most common biliary pathology. They are asymptomatic in the majority of cases. Gallstones can be divided into three main types: cholesterol, pigment (brown/black) or mixed stones.

Cholesterol or mixed stones contain 5199 per cent pure cholesterol plus an admixture of calcium salts, bile acids, bile pigments and phospholipids. The process of gallstone formation is complex and many areas remain unclear. Common in Fat, Fertile, Forty, Flatulent, Female . Common in western countries and in north India.

Obesity, high-caloric diets and certain medications (e.g. oral contraceptives) can increase secretion of cholesterol and supersaturate the bile increasing the lithogenicity of bile. Resection of the terminal ileum, which diminishes the enterohepatic circulation, will deplete the bile acid pool and result in cholesterol supersaturation.

Nucleation of cholesterol monohydrate crystals from multilamellar vesicles is a crucial step in gallstone formation. Abnormal emptying of the gall bladder function may aid the aggregation of nucleated cholesterol crystals; hence, removing gallstones without removing the gall bladder inevitability leads to gallstone recurrence.

Clinical presentation Gallstones may remain asymptomatic, being detected incidentally as imaging is performed for other symptoms. If symptoms occur, patients typically complain of right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, which may radiate to the back. This may be described as colicky, but more often is dull and constant.

Other symptoms include dyspepsia, flatulence, food intolerance, particularly to fats, and some alteration in bowel frequency. Biliary colic is typically present in 10 25 per cent of patients. This is described as a severe right upper quadrant pain which ebbs and flows associated with nausea and vomiting.

Pain may radiate to the chest. The pain is usually severe and may last for minutes or even several hours. Frequently, the pain starts during the night and wakes the patient. Minor episodes of the same discomfort may occur intermittently during the day. Dyspeptic symptoms may coexist and be worse after such an attack. As the pain resolves, the patient improves and is able to eat and drink again, often only to suffer further episodes.

It is of interest that a patient may have several episodes of this nature over a period of a few weeks and then no more trouble for some months. Jaundice may result if the stone migrates from the gall bladder and obstructs the common bile duct. Rarely, a gallstone can lead to bowel obstruction (gallstone ileus)

Effects and complications of gallstones Biliary colic Acute cholecystitis Chronic cholecystitis Empyema of the gall bladder Mucocoele Perforation Biliary obstruction Acute cholangitis Acute pancreatitis Intestinal obstruction (gallstone ileus)

When the symptoms do not resolve, but progress to continued pain with fever and leukocytosis, the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis should be considered.

Diagnosis A diagnosis of gallstone disease is based on the history and physical examination with confirmatory radiological studies, such as transabdominal ultrasonography. In the acute phase, the patient may have right upper quadrant tenderness that is exacerbated during inspiration by the examiner s right subcostal palpation (Murphy s sign). A positive Murphy s sign suggests acute inflammation and may be associated with leukocytosis and moderately elevated liver function tests.

A mass may be palpable as the omentum walls off an inflamed gall bladder. Fortunately in the majority of cases, the process is limited by the stone slipping back into the body of the gall bladder and the contents of the gall bladder escaping by way of the cystic duct. This achieves adequate drainage of the gall bladder and enables the inflammation to resolve.

If resolution does not occur, an empyema of the gall bladder may result. The wall may become necrotic and perforate, with development of localised peritonitis. The abscess may then perforate into the peritoneal cavity with a septic peritonitis however, this is uncommon, because the inflamed gall bladder is usually localised by omentum which contains the perforation

A palpable, non-tender gall bladder (Courvoisiers sign) portends a more sinister diagnosis. This usually results from a distal common duct obstruction secondary to a peripancreatic malignancy. Rarely, a non-tender, palpable gall bladder results from complete obstruction of the cystic duct with reabsorption of the intraluminal bile salts and secretion of uninfected mucus secreted by the gall bladder epithelium leading to a mucocoele of the gall bladder.

Treatment Most consider that it is safe to observe patients with asymptomatic gallstones, with cholecystectomy reserved for patients who develop symptoms or complications. However, prophylactic cholecystectomy may be considered for diabetic patients, those with congenital haemolytic anaemia and those patients who are undergoing bariatric surgery for morbid obesity as it has been found in these groups that the risk of developing symptoms s increased.

For patients with biliary colic or cholecystitis, cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice if there are no medical contraindications.

Experience shows that in more than 90 per cent of cases, the symptoms of acute cholecystitis subside with conservative measures. Non-operative treatment is based on four principles Nil per mouth (NPO) and intravenous fluid administration until the pain resolves. Administration of analgesics.

Administration of antibiotics. As the cystic duct is blocked in most instances, the concentration of antibiotic in the serum is more important than its concentration in bile. A broad-spectrum antibiotic effective against Gram- negative aerobes is most appropriate (e.g. cefazolin, cefuroxime or gentamicin) Subsequent management. When the temperature, pulse and other physical signs show that the inflammation is subsiding, oral fluids are reinstated followed by regular diet

Ultrasonography is performed to confirm the diagnosis. If jaundice is present, an MRCP is performed to exclude choledocholithiasis. If there is any concern regarding the diagnosis or presence of complications, such as perforation, a CT should be performed. Cholecystectomy may be performed on the next available list, or the patient may be allowed home to return later when the inflammation has completely resolved.

Conservative treatment must be abandoned if the pain and tenderness increase; depending on the status of the patient, either operative intervention and cholecystectomy should be performed or if the patient has comorbid conditions, a percutaneous cholecystostomy can be performed by a radiologist under ultrasound control. This will usually rapidly relieve symptoms, however an interval cholecystectomy will be required once the patient s condition has stabilised.

Provided that the operation is undertaken within 57 days of the onset of the attack, the surgeon is experienced and excellent operating facilities are available, good results are achieved. If an early operation is not indicated, one should wait approximately 6 weeks for the inflammation to subside before operating.

ACUTE CHOLECYSTITIS Commonly it occurs in a patient with pre-existing chronic cholecystitis but often also can occur as a first presentation. Usual cause is impacted gallstone in the Hartmann s pouch, obstructing cystic duct

Causative bacteria are E. coli - commonest Klebsiella, pseudomonas, proteus Strep. faecalis Salmonella Clostridium welchii

Classification 1. Acute calculous cholecystitis. 2. Acute acalculous cholecystitis

Mode of Infection Haematogenous through hepatic artery cystic artery. Portal vein. Through bile after filtering in the liver via portal circulation.

Pathogenesis of Acute Cholecystitis Stone causes obstruction at Hartmann s pouch or in cystic duct. Obstruction causes stasis, oedema of the wall, bacterial infection, acute cholecystitis and its effects. Impacted stone also causes mucosal erosion allowing bile salts to act over the submucosal tissues as bile is toxic to these tissues. It leads into necrosis, further infection and often perforation of the gallbladder usually at Hartmann s pouch

Pathology of Acute Cholecystitis Gallbladder will be distended with oedematous friable wall. Wall contains dilated vessels. Areas of necrosis and patchy gangrene may occur in severe cases. Mucosa shows ulceration and necrosis. Lumen contains infected fluid/infected bile or frank pus. Histology shows features of acute inflammation with neutrophils, oedema, and areas of necrosis and cell death.

Complications of Acute Cholecystitis Acute cholecystitis can lead to 1. Perforation, which usually occurs in the fundus or in the neck (Hartmann s). It can cause cholecysto duodenal, cholecysto-intestinal cholecysto-biliary fistula. 2. Peritonitis

Pericholecystitic abscess, empyema GB. Cholangitis and septicaemia. Empyema gallbladder, gangrenous gall bladder

Clinical Features Sudden onset of pain in the right hypochondrium, with tenderness, guarding, and rigidity. Palpable, tender, smooth, soft gallbladder. Area of hyperaesthesia between 9th and 11th ribs posteriorly on the right side (Boas s sign). Jaundice may be present. Fever, nausea, palpable tender mass in GB region (25%). Tachycardia and toxic features.

Investigations Ultrasound abdomen very useful, reveals presence or absence of gallstones; and thickening of gallbladder wall. Plain X-ray abdomen 10% of gallstones are radioopaque; also rules out other causes of acute pain abdomen. Gas is seen in emphysematous GB. Total count shows neutrophilia. HIDA/PIPIDA radioisotope study very useful. Nonvisualisation of gallbladder is diagnostic

LFT is important. Increased serum bilirubin often signifies cholangitis or stone in the CBD. Plain X-ray abdomen is not very relevant but is often important to rule out duodenal ulcer perforation, peritonitis. Only 10% of gallstones are radio-opaque. In emphysematous cholecystitis gas shadow may be seen in the region of gallbladder. Porcelain gallbladder may be seen as opacified area in gallbladder region.

Treatment Advised hospitalisation. Initially (non-operative) conservative treatment (95%): Nasogastric aspiration. IV fluids. Analgesics and antispasmodics. Broad spectrum antibiotics (cefoperazone, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime + amikacin, tobramycin,+ metronidazole {antimicrobial}). Observation. Follow-up U/S scan.

Later after 3-6 weeks, elective cholecystectomy, either by open method through right subcostal (Kocher s) incision or through laparoscopy is done. Cholecystostomy is done immediately if patient is having: 1. Empyema gallbladder 2. Persisting symptoms 3. Progressing symptoms