Guide to Media Literacy Activities for Educators

Explore a comprehensive teacher resource guide focusing on media literacy activities for students. Gain insights into instructional strategies, bias discussion, misinformation awareness, media literacy tools, and more. Enhance your classroom curriculum with engaging activities aligned with socioscientific issues.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

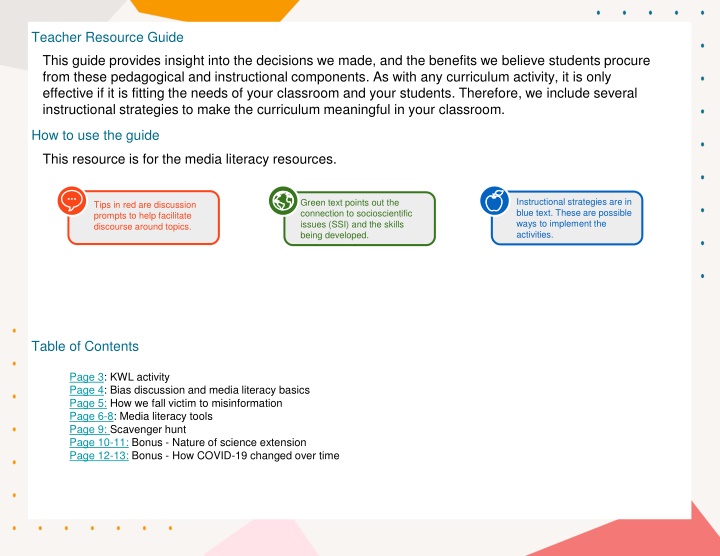

Teacher Resource Guide This guide provides insight into the decisions we made, and the benefits we believe students procure from these pedagogical and instructional components. As with any curriculum activity, it is only effective if it is fitting the needs of your classroom and your students. Therefore, we include several instructional strategies to make the curriculum meaningful in your classroom. How to use the guide This resource is for the media literacy resources. Instructional strategies are in blue text. These are possible ways to implement the activities. Green text points out the connection to socioscientific issues (SSI) and the skills being developed. Tips in red are discussion prompts to help facilitate discourse around topics. Table of Contents Page 3: KWL activity Page 4: Bias discussion and media literacy basics Page 5: How we fall victim to misinformation Page 6-8: Media literacy tools Page 9: Scavenger hunt Page 10-11: Bonus - Nature of science extension Page 12-13: Bonus - How COVID-19 changed over time

Teacher Resource: Media Literacy Research indicates students think they are much better at evaluating sources of information than they actually are. The goal for this group of activities is to provide some tools that students can use and some practice activities around the COVID outbreak. This teacher guide aligns with the slideshow titled Media Literacy Slides . Teachers are encouraged to read through the slideshow along with the teacher s guide and adapt the slideshow to best suit their classroom needs. Note: By the time you are using this resource, many of the links may be several months old. Some of these examples may be irrelevant or out of date due to the rapidly evolving nature of our knowledge about COVID-19. Teachers may feel it is helpful to update links provided with more current examples. However, if teachers choose not to update these links this opens space for a discussion about the tentative nature of scientific knowledge, and the importance of using up to date sources. Lesson Flow Activity 1. KWL activity Use to... Assess students prior knowledge of media literacy practices. Skip if... Because of the importance of pre-assessments, it is not recommended that teachers skip this. Students already have a uniform definition of bias. This activity is short and may be worth doing anyways. Students have extensive prior knowledge of media literacy. This may be worth reviewing even if students do have prior experience. The class has extensive prior knowledge of these common issues in media literacy. 2. Bias discussion Establish a class definition of the term bias to ensure everyone is discussing the same concept. 3. Media literacy basics Introduce students to the concept of media literacy and its importance. 4. Ways we fall for victim to misinformation and bias 5. Media literacy tools Illustrate examples of different information sources and the ways they influence the way information is perceived. Students are new to the idea of media literacy, or are familiar, but do not have concrete approaches to assessing information quality. Students do not have experience using media literacy tools and evaluating information quality. Address why scientific recommendations have changed throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Teach students about the emerging and tentative nature of scientific knowledge. Students already have concrete media literacy tools from other classes or programs. 6. Media literacy scavenger hunt 7. Bonus: Nature of Science Students already have extensive experience evaluating information and source quality. This unit needs to be shortened. Students are already aware of this aspect of science.

KWL for Media Literacy: How to identify strong sources of information. This can be done as a bellringer, homework, or a closing activity for the day prior to starting the media literacy module. Assigning this as a closing activity is recommended because this grants teachers more time to adjust instruction for their class. What do you know about evaluating the quality information and its source?? What have you heard about evaluating the quality of information and its source?? What incorrect information have you heard about the quality of information and its source? List the information you have encountered that you know is clearly incorrect. How do you know? Where did you find the information? What do you want to know about evaluating the quality information and its source? List questions you have about identifying high quality information. List information here that you know is true. Where did you find the information? How do you know it is factual? List the information you have heard evaluating the quality of information, but are unsure if it is factual. Where did you hear the information? What makes you wonder whether the information may not be correct? Questions to elicit student thinking during the activity (also included on slideshow): Where do we get our information? How do we know it is factual? What should we do to avoid misinformation? How do we know what we know? Why do we look for information? What does psychology tell us about how our goals impact how we interpret information motivated reasoning, confirmation bias, etc. Keeping a KWL for the class data can guide instruction and provide the teacher insight into student interests, strengths, and weaknesses.

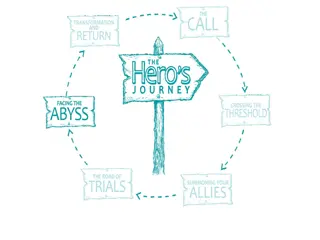

Slide 7 in slideshow Slides 5 and 6 are structured to help guide the process of creating a class definition of bias. Teacher should collect and record student definitions, add their own definition, and then finally work with the class to establish a common definition. We recommend arriving at a definition that is similar to the one listed below the preconceived ideas and judgements through which we view the world. The model to the right is has been effective in helping students visualize how bias can creep into science information at all stages from generation through communication and interpretation. This can be shown on the board to help guide class discussion of how bias can be introduced along the media production and dissemination process. Talking points when discussing bias in science can include: Discussing how traditional journalism with reporters/editors being the gatekeepers of information. Today s situation where anyone can communicate information regardless of expertise/ethics/agenda is important. The limitations of this model (ex: does not account for the friend of a friend sources common on social media).

Transition into discussing how to assess sources of information with the following talking points: In the past there was low quantity of information of high quality. Today we live in an instantaneous news cycle consisting of massive quantities of information at all levels of quality. How do we sort through the garbage? The following slides include tools to help students with this process. Slides 9-14 showcase examples of each of these types of sources in the context of misinformation. Slide 15 showcases examples of high-quality information sources. Teachers may allow students to explore these examples at this time, however more time will be devoted to engaging with these materials later. The purpose of this section is to introduce students to these examples before diving into how to recognize them.

Know Your Sources Media Literacy Tool CRAP Test Graphic Organizer Article title: Article Title: Article Author: Article Source: Article author: Article source: Currency Reliability Authors and Audiences Who created this message? Messages and Meanings What creative techniques are used to attract my attention? Representations and Reality What lifestyles, values, and points of view are represented or omitted? Bias What judgements or preconceived ideas might the author have? Who is the target Audience (and how do you know)? How might different people understand this message differently from me? Is this fact, opinion, something else (and how do I know)? What judgements or preconceived ideas might the intended audience have? Why might this message matter to me or others? Is it credible? What might the audience do with this message? Authority Purpose . How would you classify this resource? (satire, clickbait, invented news, or hyperpolitical (far left or far right)? Why did you classify this resource this way? Should this be trusted? Slides 9 and 10 explain two different tools to help students evaluate the quality of information and their sources. The teacher should select the tool they feel will work best in their classrooms. It may be helpful consulting the media specialist at the school to see what tools they have used or recommend.

Article Title: How the U.S. and Italy Traded Places on Coronavirus Article Author: Dan Diamond & Sarah Wheaton Article Source: https://www.politico.eu/article/how-the-us-and-italy-traded-places-on-coronavirus/ This is a completed example from one of the articles used in the National Comparison activity. These are nuanced evaluations and these nuances need to be made explicit for students. Authors and Audiences Who created this message? Dan Diamond was a reporter for Politico (currently with the Washington Post) who writes primarily on health care politics and policy. (https://www.politico.com/staf f/dan-diamond https://www- washingtonpost- com/people/dan-diamond/) Sarah Wheaton is the Chief Policy Correspondent for Politico Europe and formerly served as the Senior Policy Reporter for the paper s European health team (https://www.politico.eu/staff /sarah-wheaton/) Who is the target Audience (and how do you know)? Politico is an online, progressive learning journal that focuses on politics, policies, and global news. The primary audience is expected to be in the late 20s-40s. Why might this message matter to me or others? The article includes COVID infection and death rates in Italy and the United States. This article was written in June 2020 when the world was trying to figure out how to contain the virus and reopen economies. By comparing the government policies of these two countries, Politico is offering a valuable perspective to the United States. Messages and Meanings What creative techniques are used to attract my attention? Pulled block quotes draw attention to main points through color and different formatting. The structure How might different people understand this message differently from me? Right-leaning opinions might find this article to be bias in how it portrays the Trump Administration and Fox News. There is a negative tone to how the United States is handling COVID-19. What might the audience do with this message? The purpose of this article if for the audience to compare the government policies Italy and the United States implemented and their resulting effects on COVID-19 cases. Representations and Reality What lifestyles, values, and points of view are represented or omitted? This article includes COVID infection and death rates. Authors also include quotes from primary sources. These sources include health officials, local media, and political figures. When the opinions of individuals are quoted, they are used to illustrate a point of view, rather than as replacement for objective evidence. Is this fact, opinion, something else (and how do I know)? Is it credible? The article is based on evidence. Bias What judgements or preconceived ideas might the author have? Political is a left leaning publication source according to AllSides. See also the who created this message section for author reliability. What judgements or preconceived ideas might the intended audience have? Politico s primary audience is located in Washington D.C. and insiders, outsiders, lobbyists and journalists, governors, senators, and other political positions, so the audience is to have an assumed understanding of the inner workings of American and global politics. Both of these authors work for well respected journalistic institutions. They focus primarily on these topics and likely are very well educated in the topics covered by this article. These are likely trustworthy authors in this topic. The source uses evidence to tell the story, rather than the author s opinions. The author provides sources for quotes, but does not provide sources for COVID statistics. These statistics are readily available through multiple sources. Even though the authors do not cite these statistics, a quick fact check aligns them with WHO data. Although it would be better if they had directly cited the source for these numbers, these statistics are easy to locate from a reputable data source and should not be held against the reputability of the article. Although this article is several months old, pointing out to students that currency in itself is not the only determining factor of the quality of an article. This article remains relevant as none of the major points have changed. This is an important point. While the authors do quote the opinions of various figures, the authors themselves portray those as opinions rather than facts. Those opinions are used to help illustrate a particular point of view, not as evidence themselves. The authors provide balanced counterpoints to opinions where necessary, and do not insert their own opinions into the text. Teacher note: It is worth mentioning that it is very unlikely that any source will be perfect . Students will need to make a judgement call. The most important things to consider are whether the article is evidence based rather than opinion based, whether the article presents a biased presentation of the facts, whether the article is trying to sell or advance an agenda, whether the authors are knowledgeable in the area, and the reputability of the institution.

CRAP Test Graphic Organizer Article title: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard Article author: N/A Article source: Politico - https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 It is important to note that the content contains no opinions. Currency Reliability This information is kept up to date. This source is updated daily as new data becomes available. This source includes COVID-19 statistics reported by local public health organizations and compiled by the WHO. Vocabulary is simple and minimal. Data transparency is important. The fact that this source makes it clear what sources are included, why they are included, and makes raw data available helps establish trustworthiness. The content contains no opinions. The author provides references for data sources and links to raw data at https://covid19.who.int/info. Authority Purpose A weakness, but this is made up for in their data transparency. Individual authors are not cited as this information is sourced from a large number of resources. This resource contains only evidence. This source does not display bias. All sources and authors are public health officials. They are well educated in this topic. The organization is not trying to sell anything. Reputable and knowledgeable contributors. The World Health Organization published this resource. This is the leading global health organization. They work within the United Nations. Their core values are posted here: who.int/about/who-we-are/our-values. There are no advertisements on this site. This is a well established and globally trusted organization. How would you classify this resource? (satire, clickbait, invented news, or hyperpolitical (far left or far right)? Why did you classify this resource this way? Should this be trusted? This resource is a high-quality source. Although specific authors are not mentioned, this is not necessary because it is displaying information compiled from a global list of sources. How these data are sourced, what the WHO considers to be high quality data, key definitions and the WHO s data policy are easy to locate. This source is worth trusting.

ML scavenger hunt a. The Media Literacy Scavenger Hunt activities ask students to explore four articles using the tools you selected and reviewed in the previous step. The goal is to help students practice identifying information of varying quality in the context of this unit. a. Teachers should provide students independent time to work on this assignment. The amount of time necessary will vary based on the teachers approach and student ability levels. i. Teachers can elect to assign all four articles to students or divide the articles up among the class. The first option will take longer but provide students with more practice. The second option will take less time at the expense of students being able to experience each evaluation personally. a. Following independent work time, the teacher should lead the students through a guided discussion to ensure students have adequately assessed each article. Teachers should push students to elaborate on the reasoning behind their assessments. a. Use the annotated guides on pages 7 and 8 as a guide for the scavenger hunt.

Tricky Tracks Adapted from Fossil Finders Curriculum, University of Georgia- Spring 2013 To help students orient themselves to this aspect of the nature of science, we suggest teachers begin by using the Tricky Tracks resources. Teachers should use the Engage and Tricky Tracks sections as an opener for this assignment. This activity originally includes students taking field notes on a worksheet, but a group discussion may be sufficient in our context. This activity was originally designed for middle schoolers and is only being used to elicit prior knowledge in this curriculum. Because of this, we would advise spending no more than 15 or 20 minutes total on this activity. Lesson Description This lesson engages students in the nature of science and introduces them to the work of paleontologists through interpreting the geologic past. Students will learn about making observations and inferences based on evidence. Essential Questions What is the difference between and observation and an inference? Why do scientists change their hypotheses over time? How does this lesson relate to what scientists have done during COVID-19? Vocabulary Observing- the process of using one or more of your senses to gather information Inferring- The process of making an inference, an interpretation based on observations and prior knowledge Materials Tricky Tracks Overhead Slide or PowerPoint Tricky Tracks Student Worksheet (see below) Tricky-Tracks Student Worksheet It is important to consider Nature of Science ideas around emerging science information and how science works by continuously revising our understandings this is strength not a weakness, but many special interest groups use the tentative/revision aspects of science as a sign of weakness. Observations Inferences Position 1 Position 2 This worksheet is optional, but can provide additional support for students who need help keeping their ideas organized. Position 3

Tricky Tracks (15-20 minutes, try to spend about 5 minutes on each position) 1) Tell students to imagine they are part of a group of scientists working in the field in Texas that just found a set of fossilized tracks. They will be the first to investigate the tracks. Explain how each set of tracks can tell a story about what happened in the past and by observing these tracks they can infer what happened in the past. We recommend asking students to keep track of their ideas. Students may use a sheet of notebook paper, or a table such as the one labeled Student Handout on the previous page. 1) Tell students that they will be taking field notes like a scientist and recording their observations and inferences about the tracks. Have students fill in the top of the Tricky Tracks Field Notes Sheet. You may choose to use the internet to look up the weather conditions for Glen Rose, Texas to make it more authentic for students. Start with position 1 of the footprints on slide 23 keeping the other two sections covered. Using the Tricky Track Field Notes Handout, ask students to write down as many observations as they can about position 1 in the blank provided. Should it become necessary to challenge the students' thinking and stimulate the discussion, the following questions may help. In what directions did the animals move? Did they change their speed and direction? What might have changed the footprint pattern? Was the land level or irregular? Was the soil moist or dry on the day these tracks were made? In what kind of rock were the prints made? Were the sediments coarse or fine where the tracks were made? What environment could you find tracks like these today? 1) Next, have students partner with another student or several other students to discuss their observations. Allow a few minutes for students to confer with their partner(s). 1) Bring the class together and ask groups to share their observations. 1) Give students a chance to compare their interpretation with other students; you may do this in small groups or as part of a class discussion. Have students answer the questions how does your interpretation differ from your neighbors?... etc. a) E.g. of observations: one is red or one is green, students may count the number of prints or compare sizes. b) E.g. These are animal tracks or they are heading towards the same point. Inferences here include calling the marks animal tracks or stating they are moving towards the same point. One can only be sure that these as animal tracks if they observed the tracks being formed. 1) Tell students that a funding agency has given them money to excavate more of the track site. Uncover the second position, position 2, of the puzzle and allow time for the students to consider the new information. Use a think, pair, share strategy or continued group work. Students will see that the first explanation may need to be modified and new explanations may need to be added. Additionally, they might notice that not all of their interpretations are the same. Ask them to explain why there is more than one interpretation for what is happening if everyone is seeing the same picture. Have students share their observations and inferences again with the class and engage them in a similar discussion asking if their hypotheses have stayed the same or changed. Another option is to allow the student groups to critique one another s hypotheses based on the evidence they see in the picture. Discuss what an inference is and have students make their own inferences. Explain how scientists must use their observations to make inferences. You could also compare this action to being like a detective. 1) For the final position, position 3, tell students more funding has come through to unearth the rest of the track site. Reveal the complete puzzle and ask students to interpret what happened. It is important for students to understand that any reasonable explanation must be based only on those proposed explanations that still apply when the entire puzzle is projected. For an interpretation to be acceptable it must be consistent with all the evidence.

Following the Tricky Tracks introduction, students should complete the Our Knowledge of COVID-19 Over Time activity. a. Begin by assigning students to one of three stories: Hydroxychloroquine, Remdesivir, and COVID-19 transmission. b. Allow students to complete the activity sheet for their topic using either the web based or paper timeline. c. Lead a discussion about findings. Be sure to draw attention to how revisions strengthen scientific knowledge, rather than signal a weakness.

Our Knowledge of COVID-19 Over Time Like you experienced in the footprints activity, information about COVID-19 has been slowly and steadily uncovered over time. As new information was uncovered, scientists have changed their hypotheses and recommendations. In this activity you will trace how what scientists learned, believed, and recommended changed over time as they learned new information. Procedure: 1. Think back to a time when you changed your mind. What did you believe before? What do you believe now? Why did you change your mind? Write your response here: Why is it important to revise our hypotheses in light of new evidence? Why should we trust scientific recommendations now if there s the chance they will be revised in the future? What are the risks of ignoring scientific recommendations? How has distrust in scientific recommendations impacted the economy, infection rate, mortality rate, etc.? 2. Using the timeline you ve been provided, look for examples of scientists learning new information about the topic you ve been assigned. 3. Answer the reflection questions below. 1) What was an example you found of scientists revising their hypotheses and/or recommendations? What was their hypothesis? What is their hypothesis now? 2) What new evidence led to scientists revising their hypothesis? Why did scientists need to revise their hypothesis based on this evidence? A general misunderstanding of the nature of science and the resulting public distrust of science has directly impacted our response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has repercussions felt in our economy, hospitals, and day-to-day lives. 3) How might our understanding and response to the COVID-19 pandemic be different if scientists did not revise this hypothesis? 4) Why do scientists revise their hypotheses? How does revising a hypothesis over time strengthen scientific knowledge? 5) Knowing what you know about how and why scientists change their minds over time, how would you respond to the following quote? Why should I trust scientists? They ve changed their mind so many times. It s clear they don t know what they re talking about!