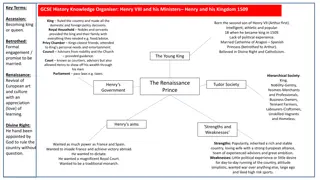

Henry VIII's Government Overview

Explore the inheritance and evolution of Henry VIII's government structure, including the Privy Chamber and Privy Council. Learn about key advisors, power struggles, and reforms during his reign as King of England.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

WHAT DID HENRY VIII INHERIT FROM HENRY VII? Henry VIII inherited many advisors from his father. One of his first acts as monarch was to execute his father s disliked leaders of the Council Learned in the Law, Richard Empson and Edmund Dudley in August 1510. Henry inherited his Lord Chancellor, Archbishop William Warham; his Lord of the Privy Seal, Bishop Richard Foxe; Lord Great Chamberlain, John de Vere, Earl of Oxford; and Principle Secretary Bishop Thomas Rothall. These advisors were often unhappy at Henry s war-mongering intentions, and they often did not see eye to eye. As these individuals died or changed their post, it was then possible for the likes of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey and many of Henry VIII s supporters to rise into these positions of power. Many of these men possessed similar desires to the King, or were much more willing to implement the King s aggressive foreign policy. Additionally,

PRIVY CHAMBER The Privy Chamber grew in size and power during the reign of Henry VIII as his minions (young courtiers such as Thomas Boleyn, Charles Brandon and William Compton, who had grown up and socialised with Henry VIII) became Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber. The Privy Chamber was part of the King s Household, and was where he ate his meals and carried out much of his day to day business to be allowed in the Privy Chamber meant you could discuss particular matters with the King which may not have been possible elsewhere. Cardinal Wolsey was not a fan of the Privy Chamber (largely due to his lack of influence over it) and tried to purge it of particularly troublesome minions in May 1519. This worked to an extent as he was able to replace these individuals with individuals who were more sympathetic to him, however, it had only limited success because as the minions were essentially the King s friends, it would be unrealistic to think they would not make their way back into service. As John Guy argued, Cardinal Wolsey tried to disguise this expulsion of the minions as governmental reform, and also targeted the leader of the Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber, the Groom of the Stool (at this time it was William Compton) by limiting the amount of money the Groom of the Stool could spend to 10,000 per year, thus trying to Compton s and the minions influence over the King. Wolsey continued to try to reform the Privy Chamber once again in 1526 with the Eltham Ordinances. As Keith Randell has suggested, although Wolsey once again painted his reforms to be about efficiency of government, the Eltham Ordinances, were actually another attempt by Wolsey to remove potential opposition from the Privy Chamber.

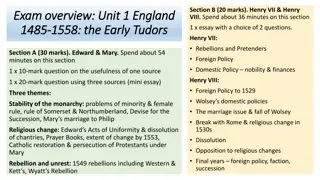

PRIVY COUNCIL The Privy Council was a group of advisors who met frequently to discuss problems and try and offer solutions to the King. In the earlier years of Henry s reign Cardinal Wolsey, then after his death, Sir Thomas More took charge of these meetings. Wolsey, concerned by his level of influence over the Council suggested reforms to the Privy Council in his 1526 Eltham Ordinances. After the execution of Cromwell in 1540, the role of the Privy Council grew as it filled the hole left by the informal, yet important, role of the King s chief minister. standardised with their own secretary to record minutes. However, it can be debated when this shift to a formal, rigid Privy Council occurred and whether it was a natural progression or a conscious change. For example, Wolsey s Eltham Ordinances largely described what the Privy Council looked like by the later 1530s, and furthermore, when responding to the Pilgrimage of Grace rebels, the Council signed off their response as the King s Privy Councillors in 1537. This evidence throws the argument that the shift to a formalised Privy Council was a sudden abrupt change upon Cromwell s execution, but rather a natural progression to plug the gap left by the vacant chief minister post. Due to the rise of faction in the early 1530s, and the rule of faction (as David Starkey has called it) of 1540s, the Privy Council became a somewhat volatile institution with individuals trying to manipulate their way to power. After the marriage to Catherine Parr in 1543, the Reformers were again more influential over policy. This culminated in the implementation of Henry VIII s will upon his death in January 1547, which led to alliances being formed within the Privy Council. The role of the Privy Council became more

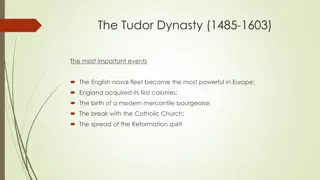

PARLIAMENT During Henry VIII s reign, much as it was in the reign of his father, Parliament met when it was requested to by the monarch. It was called usually to grant taxation; however, the Reformation Parliament of 1530s saw a significant shift in the use of Parliament as it was called to helped push through Henry s reformation of the English Church and the Break with Rome. Throughout the Wolsey years Parliament was only called twice in 1515 and 1523. Again, the main reason for calling Parliament was the need for taxation (much as it had been for Henry VII), in part due to Henry VIII s aggressive foreign policy. However, there was also discussions about anti-clericalism, although they did not accumulate to much as MPs did not pass a law which restricted the benefit of the clergy during the 1515 session of Parliament. However, there was a significant shift in how Parliament was used due to the Break with Rome. Keith Randell has suggested there is no direct evidence to suggest why Henry called this Parliament to session, however, as Randell argued, it could have been Henry s method of trying to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon through an ill- thought out plan . Although the Reformation Parliament was in session for nearly seven years, the MPs only met for 484 days during that time. During that time, the Reformation Parliament dealt with systematically reducing, and eventually removing, the power of the Catholic Church within England (see Break with Rome section for more information). Upon the fall of Cromwell in July 1540, the last Parliaments of Henry s reign (1542-1544 and 1545-1547), were again primarily for the raising of extraordinary revenue for wars against France and Scotland; Henry attacked Scotland in 1542, and attacked both France and Scotland in 1544.

CARDINAL THOMAS WOLSEY As Lord Chancellor, Cardinal Wolsey was head of the justice system within England. Keith Randell argued that although Wolsey did want to pursue reform of the justice system, he was more concerned with his own personal interests and tried to avoid the reforming actions negatively impacting his own position. Within his reforms, Wolsey championed civil law over common law. Civil law was where cases were judged with natural justice and common sense, whereas common law had been used in England since the invasion of William the Conqueror and favoured the outcomes of former cases to set a precedent with how crimes should be dealt with. Civil law (which was used within the Roman Empire) was favoured by many parts of southern Europe and intellectuals as it helped to avoid guilty individuals escaping punishment due to a slight technicality within the law. Wolsey also pushed for cases for the poor and weak to be heard in his courts as, if heard in a common law court, the legal fees were usually excessively expensive and this often meant that the rich and powerful triumphed unless a case arose which directly affected him, in which case he would focus on that instead.

COURT OF THE CHANCERY This Court was the main court of equity within England it usually judged cases through fairness, rather than a strict reading of the common law. As Lord Chancellor, Wolsey was head of the Court of the Chancery and did take his responsibilities rather seriously; he is noted as saying to a senior official of the Court of the Chancery that it was the Court of Conscience as cases should be judged fairly. He frequently presided over cases and often made the reasons for his judgements public. Within the Court, Wolsey tried to deal with as many cases as possible, such as cases relating to: enclosure; land disputes; will disputes; and contracts. The main issue with this was that the Court of the Chancery actually became too popular and cases became backlogged.

COURT OF THE STAR CHAMBER Initially set up in 1487 during the reign of Henry VII, the Court of the Star Chamber increased in prominence during the early years of Henry VIII. From 1516, Wolsey increased the availability of the Court of the Star Chamber so it was accessible to as many people as possible. Wolsey also pushed for cases which were from weaker members of society to be heard first, unless they were directly against him. Due to Wolsey s championing of the Court of the Star Chamber it, much like the Court of the Chancery, became too popular and overflow tribunals had to be set up to hear the backlogged cases. permanent committee in 1519, which was the forerunner for the Court of Requests. This led to the creation of a

FINANCIAL AND GOVERNMENT REFORM M. D. Palmer has argued that there were no significant financial reforms, except for the development of the subsidy tax in 1514, which required a strong relationship with Parliament. Wolsey implemented that instead of local commissioners assessing people s wealth, Wolsey organised a national committee for assessing wealth (which he headed) to try and combat any potential manipulation of the system by the nobility. Although this gave him a more accurate assessment of wealth within England, it still did not produce enough money to fund Henry VIII s desired war against France in 1522-1524; the 1523 subsidy yielded one shilling for every 50 worth of land owned by an individual, as well as one shilling per every pound of savings and goods that a person owned. Wolsey worsened his relationship with Parliament by calling for the Amicable Grant in 1525. It was packaged as a gift to the King, so therefore did not have to be approved by Parliament. However, it angered many individuals and nearly led to rebellion in various parts of the country. The Eltham Ordinances were a series of recommendations which essentially allowed Wolsey to remove opponents from the Privy Council and Privy Chamber however Wolsey presented them as financial reforms. Within the Ordinances which were published in 1526, Wolsey stated that there should be a group of around 20 councillors who meet every day between the hours of 10am and 2pm. Additionally, many Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber lost their positions, as did many other servant. However, the Eltham Ordinances did allow Wolsey to secure the removal of Henry VIII s Groom of the Stool, Sir William Compton, and replace him with the more biddable Henry Norris. Due to Wolsey s desire for control rather than reform, once he had achieved his actual aim, the other plans for reform within the Eltham Ordinances were conveniently forgotten. Therefore, as Keith Randell has suggested, although Wolsey once again painted his reforms to be about efficiency of government, the Eltham Ordinances, were actually another attempt by Wolsey to remove potential opposition from the Privy Chamber.

CONCLUSIONS Henry inherited many of his father s former ministers, many of whom he did not see eye to eye with. Henry VIII started his reign by using Parliament for very similar reasons to that of his father, Henry VII, albeit for a more aggressive foreign policy, yet this was still a traditional use of Parliament. Upon the fall of Wolsey and the Break with Rome, the role of Parliament developed a process which Geoffrey Elton described as one of the pillars of the Tudor revolution in government . Parliament was required to pass laws regarding the religious landscape with England. Overall, the development of the use of Parliament throughout Henry VIII s reign paved the way for its increased importance and actions in the years that followed. Wolsey carried out some reforms to government, however they were never at his expense. He would not carry out changes that had the potential to harm his position.