High Performance Computer Systems Memory Consistency

Memory consistency in high-performance computer systems as discussed by Prof. Chung-Ta King from National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan. Learn about centralized and distributed shared-memory architectures, synchronization basics, and models of memory consistency. Discover the expectations of programmers, compilers, and computer architects regarding memory operations and system optimizations.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

CS5102 High Performance Computer Systems Memory Consistency Prof. Chung-Ta King Department of Computer Science National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan (Slides are from textbook, Prof. O. Mutlu, Prof. S. Adve, Prof. K. Pingali, Prof. A. Schuster, Prof. R. Gupta) National Tsing Hua University

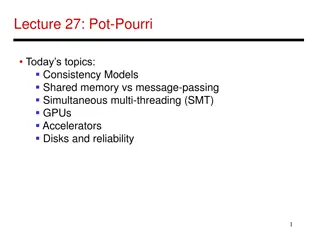

Outline Introduction Centralized shared-memory architectures (Sec. 5.2) Distributed shared-memory and directory-based coherence (Sec. 5.4) Synchronization: the basics (Sec. 5.5) Models of memory consistency (Sec. 5.6) 1 National Tsing Hua University

As a Programmer, You Expect ... Threads/processors P1 and P2 see the same memory Initially A = Flag = 0 A = 23; Flag = 1; P1 while (Flag != 1) {}; ... = A; P2 P1 writes data into variable A and then sets Flag to tell P2 that data value can be read from A P2 waits till Flag is set and then reads data from A 2 National Tsing Hua University

As a Compiler, You May ... Perform the following code movement: A = 23; Flag = 1; This is considered safe, because no data dependence Processors also reorder operations for performance Note: constraints on reordering obey dependeny Data dependences must be respected: in particular, loads/stores to a given memory address must be executed in program order Control dependences must be respected Reordering can be performed either by compiler or processor (out-of-order, OOO, architecture) Flag = 1; A = 23; 3 National Tsing Hua University

As a Computer Architecture, You May ... Load bypassing Write buffer Processor Memory system Load bypass in write buffer (WB): WB holds stores that need to be sent to memory Loads have higher priority than stores because their results are needed to keep processor busy bypass WB So, load address can be checked against addresses in WB, and WB satisfies load if there is an address match If no match, loads can bypass stores to access memory National Tsing Hua University

So, as a Programmer, You Expect ... Initially A = Flag = 0 P1 A = 23; Flag = 1; Expected execution sequence: P1 st A, 23 st Flag, 1 ... Problem: If the two writes in P1 can be reordered, it is possible for P2 to read 0 from variable A while (Flag != 1) {}; ... = A; P2 ld P2 Flag //get 0 ld ld Flag //get 1 A //get 23 X 0 5 National Tsing Hua University

Problem in Multiprocessor Context The problem becomes even more complex for multiprocessors: If a processor is allowed to reorder independent operations in its own instruction stream, (which is safe and allowed in sequential programs) will the execution of a parallel program on a multiprocessor produce correct results as expected by the programmers? Answer: no! There are data dependences across processors! 6 National Tsing Hua University

Example: Primitive Mutual Exclusion Initially Flag1 = Flag2 = 0 P1 Flag1 = 1; if (Flag2 == 0) if (Flag1 == 0) critical section Flag2 = 1; P2 critical section Possible execution sequence: P1 st Flag1,1 ld Flag2 //get 0 st ld P2 Flag2,1 Flag1 //get ? 7 National Tsing Hua University

Example: Primitive Mutual Exclusion Possible execution sequence: P1 st Flag1,1 ld Flag2 //get 0 Intuition: P1 s write to Flag1 should happen before P2 s read of Flag1 True only if reads and writes on the same processor to different locations are not reordered Unfortunately, reordering is very common on modern processors (e.g., write buffer with load bypass) st ld P2 Flag2,1 Flag1 //get ? 8 National Tsing Hua University

Mutex Exclusion with Write Buffer P2 P1 P1 enters CS P2 enters CS 0 0 ld Flag2 (WB bypass) ld flag1 (WB bypass) WB WB st Flag2,1 st Flag1,1 Shared Bus Flag1: 0 Flag2: 0 Note: we have not yet considered optimizations such as caching, prefetching, speculative execution, 9 National Tsing Hua University

Summary Uniprocessors can reorder instructions subject only to control and data dependence constraints However, these constraints are not sufficient in shared-memory multiprocessors May give counter-intuitive results for parallel programs Question: What constraints must we put on instruction reordering so that parallel programs are executed according to the expectation of the programmers? One important aspect of the constraints is memory (consistency) model supported by the processor National Tsing Hua University

Memory Consistency Models A contract between HW/compiler and programmer Hardware and compiler optimizations will not violate the ordering specified in the model Programmer should obey rules specified by the model Example: if programmers demand getting 23 at P2 P1 A = 23; while (Flag != 1) {}; Flag = 1; ... = A; // get 23 To satisfy the required memory access ordering, hardware or compiler must not perform certain optimizations, e.g. write buffer with load bypassing, to the program, even if many reorderings look safe may miss opt. chances P2 11 National Tsing Hua University

Memory Consistency Models On the other hand, if programmers acknowledge such coding may get wrong results P1 A = 23; while (Flag != 1) {}; Flag = 1; ... = A; // get ?? And are willing to let their intentions explicit P1 A = 23; V(S); P(S); ... = A; // get 23 Under such a relaxed memory model, hardware or compiler can perform optimizations on those unprotected code sequences P2 P2 12 National Tsing Hua University

Memory Consistency Models Memory consistency model is a contract Drafting a good contract requires careful tradeoffs between programmability and machine performance Preserving an expected (more accurately, agreed upon ) order usually simplifies programmer s life Ease of debugging, state recovery, exception handling Preserving an expected order often makes the hardware designer s life difficult for optimizations Stronger models Stronger constraints Fewer memory reorderings Easier to reason Lower performance 13 National Tsing Hua University

Lets Start with Uniprocessor Model Sequential programs running on uniprocessors expect sequential order Hardware executes the load and store operations in the order specified by the sequential program Out-of-order execution does not change semantics Hardware retires (reports to software the results of) loads and stores in the order specified by sequential program Advantages: Architectural state is precise within an execution Architectural state is consistent across different runs of the program easier to debug programs Disadvantage: overhead for preserving order (ROB?) 14 National Tsing Hua University

How about Multiprocessors? Intuitive view from the programmers: Operations from a given processor are executed in program order Memory operations from different processors appear to be interleaved in some order at the memory Memory switch analogy: Switch services one load or store at a time from any proc. All processors see currently serviced load/store at same time Each processor s operations are serviced in program order P1 P2 P3 Pn No cache No Wr. Buf. Memory 15 National Tsing Hua University

Sequential Consistency Memory Model A multiprocessor system is sequentially consistent (SC) if the result of any execution is the same as if the operations of all the processors were executed in some sequential order, AND the operations of each individual processor appear in this sequence in the order specified by its program This is a memory ordering model, or memory model All processors see the same order of memory ops, i.e., all memory ops happen in an order (called the global total order) that is consistent across all processors Within this global order, each processor s operations appear in sequential order Consider the memory switch analogy Lamport, How to Make a Multiprocessor Computer That Correctly Executes Multiprocess Programs, IEEE Transactions on Computers, 1979 16 National Tsing Hua University

Example of Sequential Consistency P1 P2 b1: Ry = y; b1: Ry = y; b1: Ry = y; a1: x = 1; b2: Rx = x; a1: x = 1; a1: x = 1; b2: Rx = x; a2: y = 1; b2: Rx = x; a2: y = 1; a2: y = 1; b1: Ry = y; b1: Ry = y; a2: y = 1; b2: Rx = x; a1: x = 1; b2: Rx = x; a2: y = 1; b1: Ry = y; b2: Rx = x; a1: x = 1; a2: y = 1; a1: x = 1; (Rx=0, Ry =0) 17 National Tsing Hua University

Consequences of Sequential Consistency Simple and intuitive consistent with programmers intuition easy to reason program behavior Within the same execution, all processors see the same global order of operations to memory No correctness issue Satisfies the happened before intuition Across different executions, different global orders can be observed (each of which is sequentially consistent) Debugging is still difficult (as order changes across runs) 18 National Tsing Hua University

Understanding Program Order Initially X = 2 P1 .. LD ADD ST .. r0,X r0,r0,#1 r0,X P2 .. LD ADD ST r1,X r1,r1,#1 r1,X Possible execution sequences: P1: LD r0,X P2: LD r1,X P1: ADD r0,r0,#1 P1: ST r0,X P2: ADD r1,r1,#1 P2: ST r1,X P2: LD r1,X P2: ADD r1,r1,#1 P2: ST r1,X P1: LD r0,X P1: ADD r0,r0,#1 P1: ST r0,X X=3 X=4 National Tsing Hua University

Coherence vs. Consistency Coherence concerns only one memory location Consistency concerns ordering for all locations A memory system is coherent if Can serialize all operations to that location Operations by any processor appear in program order Read returns value written by last store to that location NO guarantees on when an update should be seen NO guarantees on what order of updates should be seen A memory system is consistent if It follows the rules of its Memory Model Operations on memory locations appear in some defined order 20 National Tsing Hua University

Coherence vs. Consistency: Example Execution sequence Parallel program a2: y = 1; P1 P2 b1: Ry = y; b1: Ry = y; a1: x = 1; b2: Rx = x; a1: x = 1; b2: Rx = x; a2: y = 1; Is this execution sequence possible on SC MP? Can this sequence happen on coherent MP? How to build a machine to make this sequence happen? We thus say that sequential consistency is a stronger or stricter model than coherence 21 National Tsing Hua University

Problems with SC Memory Model Difficult to implement efficiently in hardware Straightforward implementations: No concurrency among memory accesses Strict ordering of memory accesses at each node Essentially precludes out-of-order processors Unnecessarily restrictive Many code sequences in a parallel program can actually be reordered safely, but are prohibited due to SC model What can we do about it? Ask the programmer to do more, e.g. give explicit hints, so that hardware/compiler can optimize more freely Weaken or relax the memory consistence model 22 National Tsing Hua University

Weaker Memory Consistence Models Programmers take more burden to explicitly tell the machine which sequences of code cannot be reordered and which sequences can The multiprocessor must provide programmers some means, e.g. instructions or libraries, to make such specifications It is now the responsibility of programmers to give proper specifications for parallel programs to execute correctly What is the simplest thing that programmers can do in order to relax SC? 23 National Tsing Hua University

Relaxed Model: Weak Consistency Programmers insert fence instructions in programs: Order memory operations before and after the fence All data operations before fence in program order must complete before fence is executed All data operations after fence in program order must wait for fence to complete Fences are performed in program order Synchronization primitives, such as barrier can serve as fences Fence propagates writes to and from a machine at appropriate points, similar to flushing the memory operations P1 p = new A( ) FENCE flag = true; 24 National Tsing Hua University

Weak Ordering fence Memory operations within these regions can be reordered by hardware or compiler optimizations program execution fence fence Implementation of fence: Processor has counter that is incremented when data op is issued, and decremented when data op is completed 25 National Tsing Hua University

Example of Fence Initially A = Flag = 0 P1 A = 23; fence; Flag = 1; Execution: P1 writes data into A Fence waits till write to A is completed P1 then writes data to Flag If P2 sees Flag == 1, it is guaranteed that it will read 23 from A even if memory operations in P1 before and after fence are reordered by HW or compiler P2 while(Flag != 1){}; ... = A; 26 National Tsing Hua University

Tradeoffs: Weak Consistency Advantage No need to guarantee a very strict order of memory operations Enables the hardware implementation of performance enhancement techniques to be simpler Can have higher performance than stricter ordering Disadvantage More burden on the programmer or software (need to get the fences correct) Another example of the programmer-microarchitect tradeoff 27 National Tsing Hua University

More Relaxed Model: Release Consistency Divide fence into two: one guard against before and the other against after Acquire: must complete (acquired) before all following memory accesses, e.g. operations like lock Release: can proceed only after all memory operations before release are completed (released), e.g. operations like unlock However, Acquire does not wait for memory accesses preceding it Memory accesses after release in program order do not have to wait for release K. Gharachorloo, D. Lenoski, J. Laudon, P. Gibbons, A. Gupta, and J.L. Hennessy. Memory consistency and event ordering in scalable shared-memory multiprocessors. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture, pages 15--26. May 1990. 28 National Tsing Hua University

Release Consistency Doing an acquire means that writes on other processors to protected variables will be known Doing an release means that writes to protected variables are exported and will be seen by other processors when they do an acquire (lazy release consistency) or immediately (eager release consistency) 29 National Tsing Hua University

Understanding Release Consistency From this point in this execution all processors must see the value 1 in X X 1 rel(L1) P1 X = ? X = 1 X = 1 acq(L1) X = 0 P2 t It is undefined what value is read here. It can be any value written by some processors 1 is read in the current execution. However, programmer cannot be sure 1 will be read in all executions. Programmer knows that in all executions this read returns 1. 30 National Tsing Hua University

Acquire and Release Acquire and release are not only used for synchronization of execution, but also for synchronization of memory, i.e. for propagation of writes from/to other processors Release serves as a memory-synch operation, or a flush of local modifications to all other processors A release followed by an acquire of the same lock guarantees to the programmer that all writes previous to the release will be seen by all reads following the acquire 31 National Tsing Hua University

Happened-Before Relation rel(L1) acq(L2) r(y) w(x) w(x) P1 w(y) rel(L2) r(x) rel(L1) r(x) P2 acq(L1) r(y) w(y) P3 rel(L2) acq(L2) t 32 National Tsing Hua University

Example of Acquire and Release L/S Which operations can be overlapped? ACQ L/S REL These operation orderings must be observed L/S 33 National Tsing Hua University

Comments In the literature, there are a large number of other consistency models Processor consistency, total store order (TSO), . It is important to remember that these are concerned with reordering of independent memory operations within a processor Easy to come up with shared-memory programs that behave differently for each consistency model Emerging consensus that weak/release consistency is adequate 34 National Tsing Hua University

Summary Consistency model is multiprocessor specific Programmers will often implement explicit synchronization Nothing really to do with memory operations from different processors/threads Sequential consistency: perform global memory operations in program order Relaxed consistency models: all of them rely on some notion of a fence operation that delineates regions within which reordering is permissible 35 National Tsing Hua University