HIV Infection in Pediatric Patients

Learn about the impact of HIV infection on children, including the natural history before antiretroviral therapy, different disease progression patterns, and implications for treatment. Discover the challenges and opportunities in providing care to pediatric HIV patients to improve outcomes and reduce mortality rates.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS (HIV) PEDIATRICS G . E R I C M D 4

HIV infection has become an important contributor to childhood morbidity and mortality, especially in many developing countries. Worldwide, it is estimated that nearly 2 million require antiretroviral treatment. At present only 25% of such children have an access to the antiretroviral therapy. Without access to antiretroviral therapy, 20% of vertically infected children will progress to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or death in their first yr of life and more than half of HIV-infected children will die before their fifth birthday.a

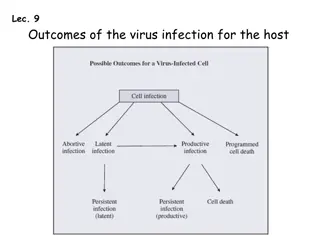

Natural History Before highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was available, three distinct patterns of disease were described in children. Approximately 10-20% of HIV-infected newborns in developed countries presented with a rapid disease course, with onset of AIDS and symptoms during the first few months of life and, if untreated, death from AIDS-related complications by 4 yr of age. In resourcepoor countries, >85% of the HIV-infected newborns may have such a rapidly progressing disease.

It has been suggested that if intrauterine infection coincides with the period of rapid expansion of CD4 cells in the fetus, it could effectively infect the majority of the body's immunocompetent cells. Most children in this group have a positive HIV-1 culture and/or detectable virus in the plasma in the first 48 hr of life. This early evidence of viral presence suggests that the newborn was infected in utero. In contrast to the viral load in adults, the viral load in infants stays high for at least the first 2 yr of life.

The majority of perinatally infected newborns (60-80%) present with a second pattern-that of a much slower progression of disease with a median survival time of 6 yr. Many patients in this group have a negative viral culture or PCR in the 1st week of life and are therefore considered to be infected intrapartum. In a typical patient, the viral load rapidly increases by 2-3 months of age (median 100,000 copies/ml) and then slowly declines over a period of 24 months. This observation can be explained partially by the immaturity of the immune system in newborns and infants.

The third pattern of disease (i.e. longterm survivors) occurs in a small percentage ( <5%) of perinatally infected children who have minimal or no progression of disease with relatively normal CD4 counts and very low viral loads for longer than 8 yr. HIV-infected children have changes in the immune system that are similar to those in HIV-infected adults. CD4 cell depletion may be less dramatic because infants normally have a relative lymphocytosis. Therefore, for example, a value of 1,500 CD4 cells/mm3 in children <1 yr of age is indicative of severe CD4 depletion and is comparable to <200 CD4 cells/ mm3 in adults.

Clinical Manifestations The clinical manifestations of HIV infection vary widely among infants, children and adolescents. In most infants, physical examination at birth is normal. Initial signs and symptoms may be subtle and nonspecific, such as lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, failure to thrive, chronic or recurrent diarrhea, interstitial pneumonia, or oral thrush and may be distinguishable from other causes only by their persistence.

Whereas systemic and pulmonary findings are common in the United States and Europe, chronic diarrhea, wasting and severe malnutrition predominate in Africa. Symptoms found more commonly in children than adults with HIV infection include recurrent bacterial infections, chronic parotid swelling, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis and early onset of progressive neurologic deteriorationThe pediatric HIV disease is staged by using two parameters: clinical status and degree of immunologic impairment

WHO clinical staging of HIV/AIDS in children with confirmed infection Clinical stage 1 Asymptomatic Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy Clinical stage 2 Unexplained persistent hepatosplenomegaly Papular pruritic eruptions Fungal nail infection Angular cheilitis Lineal gingival erythema Extensive wart virus infection Extensive molluscum contagiosum Recurrent oral ulceration Unexplained persistent parotid enlargement Herpes zoster Reacurrent or chronic upper respiratory tract infections (otitis media, otorrhea, sinusitis, tonsillitis)

Clinical stage 3 Unexplained moderate malnutrition or wasting not adequately responding to standard therapy Unexplained persistent diarrhea (14 days or more) Unexplained persistent fever (above 37.5 C intermittent or constant, for longer than one month) Persistent oral candidiasis (after the first 6-8 weeks of life) Oral hairy leukoplakia Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis/periodontitis Lymph node tuberculosis Pulmonary tuberculosis Severe recurrent bacterial pneumonia Symptomatic lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis Chronic HIV-associated lung disease including bronchiectasis Unexplained anemia ( <8 g/ dl), neutropenia ( <0.5 x 109 /1) or chronic thrombocytopenia ( <50 x 109 /1).

Clinical stage 4b Unexplained severe wasting, stunting or severe malnutrition not responding to standard therapy Pneumocystis pneumonia Recurrent severe bacterial infections (e.g. empyema, pyomyositis, bone or joint infection, meningitis, but excluding pneumonia) Chronic herpes simplex infection (orolabial or cutaneous of more than one month's duration or visceral at any site) Esophageal candidiasis (or candidiasis of trachea, bronchi or lungs) Extra pulmonary/ disseminated TB Kaposi sarcoma Cytomegalovirus infection: retinitis or CMV infection affecting another organ, with onset at age > 1 mo Central nervous system toxoplasmosis (after one month of life) Extrapulmonary cryptococcosis (including meningitis) HIV encephalopathy Disseminated endemic mycosis (extrapulmonary histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis) Disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial infection Chronic cryptosporidiosis (with diarrhea) Chronic isosporiasis Cerebral or B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy Symptomatic HIV-associated nephropathy or HIV-associated cardiomyopathy

Opportunistic Infections Children with HIV infection and advanced or severe immunosuppression are susceptible to develop various opportunistic infections. The important pathogens include Pneumocystis jiroveci, Cryptosporidium, Cryptococcus, Isospora and CMV.

Respiratory Diseases Pneumocystis pneumonia Pneumocystis jiroveci (previously P. carinii) pneumonia (PCP) is the opportunistic infection that led to the initial description of AIDS. PCP is one of the commonest AIDS defining illnesses in children in the US and Europe. However, data regarding the incidence of PCP in children in other parts of the world are scarce. The majority of the cases occur between 3rd and 6th months of life. Even if a child develops PCP while on prophylaxis, therapy may be started with cotrimoxazole. This is because the prophylaxis may have failed because of poor compliance, or unusual pharmacokinetics. Untreated, PCP is universally fatal. With the use of appropriate therapy, the mortality decreases to less than 10%.

Recurrent bacterial infections In various studies from developing countries, up to 90% of HIV-infected children had history of recurrent pneumonias. Initial episodes of pneumonia often occur before the development of significant immunosupression. As the immunosupression increases the frequency increases. In various studies from developing countries, up to 90% of HIV-infected children had history of recurrent pneumonias. Initial episodes of pneumonia often occur before the development of significant immunosupression. As the immunosupression increases the frequency increases.

Tuberculosis With the spread of the HIV infection, there has been resurgence in tuberculosis. Coexistent TB and HIV infections accelerate the progression of both the diseases. HIV infected children are more likely to have extrapulmonary and disseminated tuberculosis; the course is also likely to be more rapid. An HIV infected child with tubercular infection is more likely to develop the disease than a child without HIV infection. The overall risk of active TB in children infected with HIV is at least 5- to 10-fold higher than that in children not infected with HIV. All HIV-infected children with active TB should receive longer duration of antitubercular therapy. A 9-12 month therapy is preferred.

Viral infections Infections caused by respiratory syncytial virus, influenza and parainfluenza viruses result in symptomatic disease more often in HIV infected children in comparison to noninfected children. Infections with other viruses such as adenovirus and measles virus are more likely to lead to serious sequelae than with the previously mentioned viruses.

Fungal infections Pulmonary fungal infections usually present as a part of disseminated disease in immunocompromised children. Primary pulmonary fungal infections are uncommon. Pulmonary candidiasis should be suspected in any sick HIV-infected child with lower respiratory tract infection that does not respond to the common therapeutic modalities. A positive blood culture supports the diagnosis of invasive candidiasis.

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis (LIP) LIP has been recognized as a distinctive marker for pediatric HIV infection and is included as a Class B conditio11 in the revised CDC criteria for AIDS in children. In absence of antiretroviral therapy, nearly 20% of HIV-infected children developed LIP. The etiology and pathogenesis of LIP are not well understood. Suggested etiologies include: an exaggerated immunologic response to inhaled or circulating antigens, and/or primary infection of the lung with HIV, EpsteinBarr virus (EBV), or both. LIP is characterized by nodule formation and diffuse infiltration of the alveolar septae by lymphocytes, plasmacytoid lymphocytes, plasma cells and immunoblasts. There is no involvement of the blood vessels or destruction of the lung tissue. Children with LIP have a relatively good prognosis compared to other children who meet the surveillance definition of AIDS.

Gastrointestinal Diseases The pathologic changes in the gastrointestinal tract of children with AIDS are variable and can be clinically significant. A variety of microbes can cause gastrointestinal disease, including bacteria (salmonella, campylobacter, Mycabacterium avium intracellulare complex), protozoa (giardia, cryptosporidium, isospora, microsporidia), viruses (CMV, HSV, rotavirus) and fungi (Candida). The protozoa! infections are most severe and can be protracted in children with severe immunosuppression. Children with cryptosporidium infestation can have severe diarrhea leading to hypovolemic shock. AIDS enteropathy, a syndrome of malabsorption with partial villous atrophy not associated with a specific pathogen, is probably the result of direct HIV infection of the gut.

Neurologic Diseases The incidence of central nervous system involvement in perinatally infected children may be more than 50% in developing countries but lower in developed countries, with a median onset at about one and a half yr of age. The most common presentation is progressive encephalopathy with loss or plateau of developmental milestones, cognitive deterioration, impaired brain growth resulting in acquired microcephaly and symmetric motor dysfunction.

Meningitis due to bacterial pathogens, fungi such as Cryptococcus and a number of viruses may be responsible. Toxoplasmosis of the nervous system is exceedingly rare in young infants, but may occur in HIVinfected adolescents; the overwhelming majority of these cases have serum IgG antitoxoplasma antibodies as a marker of infection. The management of these conditions is similar to that in non-HIV-infected children; the response rates and outcomes may be poorer.

Cardiovascular Involvement Cardiac abnormalities in HIV-infected children are common, persistent and often progressive; however, the majority of these are subclinical. Left ventricular structure and function progressively may deteriorate in the first 3 yr of life, resulting in increased ventricular mass in HIVinfected children. Electrocardiography and echocardiography are helpful in assessing cardiac function before the onset of clinical symptoms.

Renal Involvement Nephropathy is an unusual presenting symptom of HIV infection, more commonly occurring in older symptomatic children. Nephrotic syndrome is the most common manifestation of pediatric renal disease, with azotemia and normal blood pressure. Polyuria, oliguria and hematuria have also been observed in some patients.

Diagnosis All infants born to HIV-infected mothers test antibodypositive at birth because of passive transfer of maternal HIV antibody across the placenta. Most uninfected infants lose maternal antibody between 6 and 12 months of age. As a small proportion of uninfected infants continue to have maternal HIV antibody in the blood up to 18 months of age, positive IgG antibody tests cannot be used to make a definitive diagnosis of HIV infection in infants younger than this age. In a child older than 18 months of age, demonstration of IgG antibody to HIV by a repeatedly reactive enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and confirmatory test (e.g. Western blot or immunofluorescence assay) can establish the diagnosis of HIV infection.

Specific viral diagnostic assays, such as HIV DNA or RNA PCR, HIV culture, or HIV p24 antigen immune dissociated p24 (ICD-p24), are essential for diagnosis of young infants born to HIV infected mothers. By 6 months of age, the HIV culture and/or PCR identifies all infected infants, who are not having any continued exposure due to breast feeding.

Management The management of HIV infected child includes antiretroviral therapy, prophylaxis and treatment of opportunistic infections and common infections, adequate nutrition and immunization.

Antiretroviral Therapy Decisions about antiretroviral therapy for pediatric HIVinfected patients are based on the magnitude of viral replication (i.e. viral load), CD4 lymphocyte count or percentage and clinical condition. A child who has WHO stage 3 or 4 clinical disease should receive ART irrespective of the immunologic stage. Children who are asymptomatic or have stage 1 or 2 disease may be started on ART if they have evidence of advanced or severe immunosupression.

However, current evidence shows that young children less than 2 yr of age have a higher risk of mortality without ART. The World Health Organization now recommends initiation of ART for all HIV infected children less than 2 yr age irrespective of clinical symptoms and the immunologic stage. Availability of antiretroviral therapy has transformed HIV infection from a uniformly fatal condition to a chronic infection, where children can lead a near normal life. The currently available therapy does not eradicate the virus and cure the child; it rather suppresses the virus replication for extended periods of time.

The 3 main groups of drugs are nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI), nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) and protease inhibitors (PI). Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is a combination of 2 NRTis with a PI or a NNRTI.

The national program for management of HIV infected children recommends a combination of zidovudine, lamivudine and nevi.rapine as the first line therapy. The alternative regimen is a combination of stavudine, lamivudine and nevirapine and these are administered using a weight-band based dosing system (NACO guidelines).a

Cotrimoxazole Prophylaxis . In resource-limited settings, cotrimoxazole prophylaxis is recommended for all HIV exposed infants starting at 4-6 weeks of age and continued until HIV infection can be excluded. Cotrimoxazole is also recommended for HIVexposed breastfeeding children of any age and cotrimoxazole prophylaxis should be continued until HIV infection can be excluded by HIV antibody testing (beyond 18 months of age) or virological testing (before 18 months of age) at least six weeks after complete cessation of breastfeeding.

All children younger than one yr of age documented to be living with HIV should receive cotrimoxazole prophylaxis regardless of symptoms or CD4 percentage. After one yr of age, initiation of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis is recommended for symptomatic children (WHO clinical stages 2, 3 or 4 for HIV disease) or children with CD4 <25%. All children who begin cotrimoxazole prophylaxis (irrespective of whether cotrimoxazole was initiated in the first yr of life or after that) should continue until the age of five yr, when they can be reassessed.

Nutrition It is important to provide adequate nutrition to HIVinfected children. Many of these children have failure to thrive. These children will need nutritional rehabilitation. In addition, micronutrients like zinc may be useful Immunization The vaccines that are recommended in the national schedule can be administered to HIV infected children except that symptomatic HIV infected children should not be given the oral polio and BCG vaccines.

Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) The risk of MTCT can be reduced to under 2% by interventions that include antiretroviral (ARV) prophylaxis given to women during pregnancy and labor and to the infant in the first weeks of life, obstetrical interventions including elective cesarean delivery (prior to the onset of labor and rupture of membranes) and complete avoidance of breastfeeding

Antiretroviral drug regimens for treating pregnant women For HIV-infected pregnant women in need of ART for their own health, ART should be administered irrespective of gestational age and is continued throughout pregnancy, delivery and thereafter (recommended for all HIV-infected pregnant women with CD4 cell count <350 cells/mm3 , irrespective of WHO clinical staging; and for WHO clinical stage 3 or 4, irrespective of CD4 cell count).

Recommended regimen for pregnant women with indication for ART is combination of zidovudine (AZT), lamivudine (3TC) and nevirapine (NVP) or efavirenz (EFV) during antepartum, intrapartum and postpartum period; EFV-based regimens should not be newly- initiated during the first trimester of pregnancy. Recommended regimen for pregnant women who are not eligible for ART for their own health, but for preventing MTCT is to start ART as early as 14 weeks gestation or as soon as possible when women present late in pregnancy, in labor or at delivery.

Two options are available Option 1. Daily AZT in antepartum period, combination of single dose of NVP at onset of labor and dose of AZT and 3TC during labor followed by combination of AZT and 3TC for 7 days in postpartum period. Option 2. Triple antiretroviral drugs starting as early as 14 week of gestation until one week after all exposure to breast milk has ended (AZT + 3TC + LPV or AZT + 3TC + ABC or AZT + 3TC + EFV) where ABC abacavir, LPV lopinavir.

Omission of the single dose-NVP and AZT +3TC intraand postpartum may be considered for women who received at least four week of AZT before delivery. If a woman received a three-drug regimen during pregnancy, a continued regimen of triple therapy is recommended for mother through the end of the breastfeeding period.

Regimens for Infants Born to HIV Positive Mothers (a) If mother received only AZT during antenatal period: For breastfeeding infants. Daily NVP from birth until one wk after all exposure to breast milk has ended. The dose of nevirapine is 10 mg/ day PO for infants <2.5 kg; 15 mg/ day PO for infants more than 2.5 kg. For nonbreastfeeding infants. Daily AZT or NVP from birth until 6 wk of age. The dose of AZT is 4 mg/kg PO per dose twice a day.

(b) If mother received triple drug ART during pregnancy and entire breastfeeding: Daily AZT or NVP from birth until 6 weeks of age irrespective of feeding

lntrapartum lntervetions Avoid artificial rupture of membranes (ARMs) unless medically indicated. Delivery by elective cesarean section at 38 weeks before onset of labor and rupture of membranes should be considered. Avoid procedures increasing risk of exposure of child to maternal blood and secretions like use of scalp electrodes.

Breastfeeding Breastfeeding is an important modality of transmission of HIV infection in developing countries. The risk of HIV infection via breastfeeding is highest in the early months of breastfeeding. Factors that increase the likelihood of transmission include detectable levels of HIV in breast milk, the presence of mastitis and low maternal CD4+ T cell count. Exclusive breastfeeding has been reported to carry a lower risk of HIV transmission than mixed feeding. Mothers known to be HIV-infected should only give commercial infant formula milk as a replacement feed when specific conditions are metWHO recommends that the transition between exclusive breastfeeding and early cessation of breastfeeding should be gradual and not an "early and abrupt cessation". Replacement feeding should be given by katori spoon

Conclusion HIV infection in children is a serious problem in many developing countries. The severe manifestations of HIV infection, conditions resulting from severe immunosupression and drug toxicities may require intensive care. Development of a vaccine to prevent HIV infection is the high priority area. There is also need to find have more efficacious antiretroviral drugs that have fewer adverse effects. Making available antiretroviral therapy at an affordable cost remains a big challenge. On short-term there is a need to find effective ways to control vertical transmission from mother to child. It may help in substantial reduction in childhood HIV infection load.