Impact of Tying Agreements in Antitrust Law

Explore the economic impact of tying agreements in modern labor economics and public policy, with insights into anticompetitive effects and legal cases like IBM and American Can. Learn how tying arrangements can affect market competition and monopolistic power.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

MODERN LABOR ECONOMICS THEORY AND PUBLIC POLICY THEORY AND PRACTICE Industrial Organization 12THEDITION 5THEDITION 21 CHAPTER CHAPTER Antitrust: Public Policy Towards Vertical Restraints of Trade and Group Boycotts 1 12 April 2025

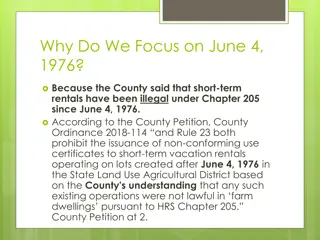

21.1 Tying Agreements If a firm has market power over good X, it may require that its buyers purchase another good, good Y (the tied product), to obtain good X (the tying product). Opinions on the economic impact of tying vary widely. Some believe that tying is never anticompetitive. Others believe that, under certain circumstances, tying can be an effective method of increasing monopoly power and monopoly profits. Conventional wisdom rejects the extreme position that tying is never anticompetitive, but accepts that most tying agreements have few anticompetitive effects. As an example of anticompetitive effects, before 1956, Kodak sold photographic film only on the condition that the buyer had to have the film processed by Kodak. Kodak controlled 90 percent of the non-instant film market, making it extremely difficult for independent film processors to find any film to process. The tying arrangement thus foreclosed a huge share of the processing market, making entry into film-processing very difficult: the only way to enter this market was to follow Kodak s lead and produce film as well as provide processing services, which greatly increased the capital barrier to entry. Entry required not only more capital, but also large research and development expenditures to produce non-infringing film capable of competing with Kodak s film. No competitor threatened Kodak s processing market share until 1956 when Kodak agreed to a consent decree ending the tie. Shortly thereafter, the processing market became highly competitive. 12 April 2025 2

21.1 Tying Agreements Defendants have advanced two primary arguments to justify tying arrangements. First, they contend that tying is necessary for technological reasons. This argument sometimes makes sense, but often is almost frivolous, as when International Salt contended that only its salt would prevent its salt dispensing machines from clogging. Second, franchisers such as Carvel and Dunkin Donuts have argued that it is necessary to tie ingredients together to maintain the high quality associated with their trademarks. These arguments have met with some success in the courts. IBM(1936) IBM refused to lease its tabulating machines unless the lessee agreed to purchase its entire requirements of tabulating cards from IBM. IBM had significant market power in the machine market, and under this plan it was able to control over 80 percent of the market for both machines and cards. IBM argued that the tie was necessary to protect its tabulating machines from damage caused by the use of "inferior" cards. Its defense was undermined by the fact that the United States government, under the provisions of its lease, had for years produced large quantities of its own cards that were successfully used in IBM's machines. 12 April 2025 3

21.1 Tying Agreements IBM(1936), continued The Supreme Court ruled that the tying agreement violated section 3 of the Clayton Act. Despite the decision, IBM continued to dominate the tabulating card market because its lessees continued to purchase their cards from IBM. In fact, IBM's card market share actually increased to 90 percent in 1954. In 1956, IBM agreed to a consent decree that required its market share in tabulating cards to be reduced below 50 percent. American Can (1949) The American Can case dealt with the leasing practices of American Can and Continental Can. Both firms adopted a policy of leasing can-closing machines for a minimum of five years, with the further restriction that the lessee purchase its entire can requirements during the five-year period exclusively from its machinery supplier, and neither company offered machines for sale. These policies resulted in a two-firm concentration ratio of 80. The practices had several possible anticompetitive effects. 1. Placing approximately 80 percent of all can customers beyond the reach of competitors each year, the long-term leases reduced the potential market available to new can manufacturers. 2. By refusing to sell their machines, American and Continental eliminated any potential competition from a secondhand machinery market. 3. The requirement that lessees purchase their requirements of cans from their machinery supplier established a tie between machinery and cans. 12 April 2025 4

21.1 Tying Agreements Jerrold (1960) In December 1950, Jerrold Electronics installed America s first cable TV system in Lansford, Pennsylvania. After a short time, the system developed technical problems that required Jerrold to develop new equipment and techniques for cable installations. Because of these problems, Jerrold decided that it would install community-wide systems only if the community agreed to purchase all the necessary equipment from Jerrold and further agreed to purchase a Jerrold service contract. The District Court ruled that, in the early years of the cable TV industry, the tie was justified by technological necessity. The Court stated further, however, that Jerrold could not continue indefinitely to sell only complete cable systems. Before the Jerrold decision, it appeared that tying agreements were on the verge of being declared illegal per se. The Supreme Court affirmed the Jerrold decision without comment and thereby established an acceptable technology defense in tying cases. 12 April 2025 5

21.1 Tying Agreements Hyde (1984) Dr. Hyde was a board-certified anesthesiologist who applied to join the staff of Jefferson Parish Hospital in New Orleans in 1976. Although the medical staff found Dr. Hyde to be a highly qualified anesthesiologist, the hospital board denied him staff privileges because it had signed an exclusive contract with Roux & Associates, a group of four anesthesiologists, to provide all the hospital s anesthesia services. Hyde then sued Jefferson Parish Hospital. The District Court ruled in favor of the hospital finding that the anticompetitive effects were minimal and were outweighed by economic benefits. The Court of Appeals, however, reversed, ruling that the contract involved a tying arrangement that was illegal per se under the Clayton Act. On appeal, the Supreme Court reversed the Appeals Court. In its reversal, the Supreme Court greatly restricted the use of the per se rule in tying cases and established a significant change in the Court s interpretation of Section 3 of the Clayton Act. The Supreme Court recognized that the contract between Jefferson Parish Hospital and Roux & Associates established a tie between hospital operating room services at Jefferson Parish Hospital, the tying product, and anesthesia services of Roux & Associates, the tied product. 12 April 2025 6

21.1 Tying Agreements Hyde (1984), continued The Court ruled, however, that because patients were free to seek services at many other hospitals in the New Orleans area, the hospital did not have sufficient market power in the tying product market, operating room services, to establish a violation of the Clayton Act. In fact, only 30 percent of the patients residing in the Jefferson Parish geographic area used Jefferson Parish Hospital for medical services. The Court noted, there is no evidence that any patient who was sophisticated enough to know the difference between two anesthesiologists was not also able to go to a hospital that would provide him with the anesthesiologist of his choice. In the Hyde decision, the Supreme Court came precariously close to explicitly overturning the per se rule in all tying cases. Furthermore, in their concurring decision, four Justices O Connor, Burger, Powell, and Rehnquist wanted to explicitly require a Rule of Reason interpretation in tying cases. The majority, however, supported the following limited per se rule. 12 April 2025 7

21.1 Tying Agreements Our cases have concluded that the essential characteristic of an invalid tying arrangement lies in the seller s exploitation of its control over the tying product to force the buyer into the purchase of a tied product that the buyer either did not want at all or might have preferred to purchase elsewhere on different terms. When such forcing is present, competition on the merits in the market for the tied item is restrained and the Sherman Act is violated. The Hyde ruling is the Supreme Court s most recent pronouncement with regard to tying arrangements, and the decision makes it clear that a tie is illegal per se only if market power in the tying product is significant enough to force buyers to purchase the tied product. It is difficult to understand why this interpretation qualifies as a per se interpretation, because, under the Hyde precedent, defendants always have the right to attempt to prove insufficient market power over the tying product. 12 April 2025 8

21.1 Tying Agreements Kodak (1992) Kodak was a leading producer of micrographic equipment and copiers and also supplied repair parts and service for their equipment through a network of Kodak trained technicians. The equipment market is referred to as the foremarket and the service and parts market is referred to as the aftermarket. Kodak faced competition in the foremarket from many firms including Xerox, IBM, Bell and Howell, 3M, and several Japanese manufacturers, and therefore, there was no disputing that they did not have monopoly power in that market. There were many independent service firms that serviced Kodak equipment and for years these firms purchased replacement parts from Kodak. In 1985, Kodak changed its policy and announced that it would only sell parts to the buyers of Kodak micrographic and copying equipment. Kodak also took steps to prevent buyers of its equipment from purchasing parts from Kodak and then reselling them to independent service organizations (ISOs). Without the parts the ISOs couldn t service Kodak equipment. Through these policies, Kodak was able to monopolize the market for repair services for Kodak equipment. The independent service organizations then sued Kodak. 12 April 2025 9

21.1 Tying Agreements Kodak (1992), continued Kodak s basic defense was that because it had no monopoly power in the foremarket, it couldn t have any monopoly power in the aftermarket. Kodak contended that if it charged monopoly prices in the aftermarket for parts and service, it would encourage buyers to purchase equipment from Kodak s competitors. The Supreme Court upheld the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reversal of the District Court s decision to dismiss the case. The Ninth Circuit based its decision on two main points: "First, Kodak will not sell replacement parts for its equipment to Kodak equipment owners unless they agree not to use ISOs. Second, Kodak will not knowingly sell replacement parts to ISOs." The court also noted that Kodak admitted that the purpose of its policy was to prevent ISOs from competing with Kodak's service network. Upon remand in August 1997 the Ninth Circuit Court affirmed a jury verdict that awarded the ISOs $72 million in treble damages. It also upheld a 10-year injunction that required Kodak to sell parts to ISOs at non- monopoly and nondiscriminatory prices. 12 April 2025 10

21.1 Tying Agreements The Kodak precedent has not generally been upheld in the courts, and in 2011 the Maryland District Court essentially overturned the Kodak precedent. Oc North America (2011) Oc is a Netherlands based company that is a subsidiary of the Japanese conglomerate Canon. Oc manufactures high speed continuous form printers that utilize large spools of perforated paper. Their printers are capable of printing hundreds, or even thousands, of pages per minute. Oc printers range in price from $100,000 to over $1 million and have a usable life of approximately 20 years. MCS does not manufacture printers, but Oc and MCS compete in providing maintenance services for Oc s printers. Initially, Oc filed a patent infringement complaint alleging that a former Oc employee had illegally stolen Oc s trade secrets and handed them over to his new employer MCS. MCS retaliated by filing a Section 2 monopolization suit contending that according to the Kodak precedent Oc had illegally monopolized the market for servicing Oc printers. The Maryland District Court dismissed MCS s complaint. 12 April 2025 11

21.1 Tying Agreements Oc North America (2011), continued In its antitrust complaint, MCS used all of the major arguments that the Supreme Court had accepted in the Kodak case, including life cycle cost information asymmetry, high switching costs, and service lock-in. The Maryland District Court accepted Oc 's argument that its printers were so expensive and so technologically advanced that its customers had to be sophisticated and knowledgeable enough that they would make the necessary financial calculations to ascertain the relevant cost information in order to make intelligent decisions regarding whether or not to purchase non-Oc competitive printers if the cost of Oc s printers and service was too high. The court also noted that unlike Kodak, there were no allegations that Oc had refused to allow its customers to seek maintenance services from non-Oc service providers or that it had taken any steps to tie its aftermarket parts and servicing of its printers to its printer sales. The Court noted that Oc is certainly free to compete with independent service companies by leveraging its own intellectual property. Basically, the District Court rejected most of the arguments used to find Kodak in violation of Section 2 in 1992. 12 April 2025 12

21.2 Cases Dealing with Franchising Agreements Carvel (1964) In 1955, Carvel operated a chain of 400 retail stores that sold soft ice cream. Before 1955, the franchisees were required to purchase their entire requirements of supplies, machinery, equipment, and paper goods from Carvel or Carvel-approved sources. In 1955, Carvel changed the standard agreement so that its dealers were required to purchase only supplies which are a part of the end product from Carvel. Under the new agreement, franchisees were permitted to purchase machinery, equipment, and paper goods from independent sources. The Court of Appeals ruled that Carvel s tying practices were legal because the agreements protected the Carvel trademark and affected an insubstantial amount of commerce. The Carvel case suggested that franchisers could protect their trademark by taking actions to ensure the quality of the products sold at each outlet. In the 1971 Chicken Delight case, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals limited the right of the franchiser to restrict its franchisees behavior. 12 April 2025 13

21.2 Cases Dealing with Franchising Agreements Chicken Delight (1971) Chicken Delight operated several hundred fast food chicken outlets. It required its franchisees to purchase a specified number of chickens and all of their supplies and mixes exclusively from Chicken Delight. Because Chicken Delight received no royalties or fees, its income was completely dependent on the revenues generated from selling the tied products to its dealers. The Circuit Court ruled that the agreement violated the Clayton Act because Chicken Delight could have effectively specified quality standards for the purchase of cooking equipment and ingredients from independent suppliers. At first, the Carvel and Chicken Delight decisions might appear to be at odds with each other; however, the two decisions simply reflect a justifiable Rule of Reason approach to franchise agreements. In the Carvel decision, the Court majority believed that it was impossible for Carvel to effectively police the quality of ingredients used in its ice cream products. In the Chicken Delight case, the Court believed that it was possible for Chicken Delight to set quality standards for chicken and spices. 12 April 2025 14

21.3 Exclusive Dealing Agreements Under an exclusive dealing arrangement, a buyer agrees to purchase its entire requirements of some product or service from one supplier. The potential anticompetitive effects of a requirements contract are highly dependent on the market power of the supplier. If a manufacturer with a small market share entered into a requirements contract, a relatively small share of the market would be foreclosed. However, if a dominant firm followed an exclusive dealing policy, a great deal of foreclosure could occur, and entry barriers might be significantly increased. A Rule of Reason approach, therefore, is justified with respect to exclusive dealing. Unlike tying agreements, which tend to benefit sellers but not buyers, exclusive dealing arrangements provide economic benefits to both buyers and sellers. The Standard Oil case concerned the use of requirements contracts in the retail gasoline market. 12 April 2025 15

21.3 Exclusive Dealing Agreements Standard Oil Of California (1949) Under Standard Oil s contracts, independent service stations agreed to purchase their entire supply of gasoline from Standard Many of the contracts also required the retailers to purchase all of their tires, tubes, batteries, and accessories from Standard. Standard Oil had negotiated almost 6000 requirements contracts with independent dealers in the Southwest. The government contended that these contracts foreclosed a substantial amount of the gasoline market, thereby creating a barrier to entry into the oil refining industry. In the Justice Department s view, elimination of the contracts would encourage retailers to become split pump stations, that is, stations carrying more than one brand of gasoline. The government hoped that the end of requirements contracts would open the market to new independent refiners, encourage price competition, and give independent retailers more bargaining power vis- -vis the major refiners. Although the requirements contracts foreclosed some markets from independent refiners, it is not clear that the overall effect of the contracts was to hinder competition or hurt the independent refiners. 12 April 2025 16

21.3 Exclusive Dealing Agreements Standard Oil Of California (1949), continued The contracts provided both the refiner and the retailer with benefits. They assured small independent retailers of a continuing supply of gasoline and afforded some short-run protection from unforeseen price increases. An independent retailer could therefore plan its competitive strategy on the basis of known costs and avoid the risk of storing a product with a fluctuating demand. From the independent refiners viewpoint, the contracts lowered selling costs by reducing transaction costs and reduced uncertainty by protecting refiners from a rapid reduction in demand. The Supreme Court recognized that the requirements contracts might have net economic benefits but nevertheless ruled that they violated the Clayton Act. According to a slim 5-4 majority, Standard s foreclosure of 6.7 percent of the market indicated a reasonable probability that competition would be substantially reduced. The Court majority found against Standard Oil despite a recognition that the decision might result in increased vertical integration by refiners into retailing and that such increased vertical integration might be more anticompetitive than the condemned requirements contracts. 12 April 2025 17

21.3 Exclusive Dealing Agreements Tampa Electric (1961) In 1955, Tampa Electric, a regulated public utility, made plans to construct six additional generating facilities. Although all the existing generating plants in peninsular Florida burned oil, Tampa Electric decided to burn coal in the first two new generators and contracted with Nashville Coal to supply its entire coal requirements for a period of 20 years. The contract set a minimum price of $6.40 per ton; the future price was to be adjusted with changes in production costs. Tampa Electric spent $3 million more to build the coal-burning plants compared with the cost of building oil-burning facilities, and Nashville spent $7.5 million preparing to meet the conditions of the contract. In April 1957, immediately before the first scheduled coal delivery, Nashville informed Tampa Electric that the contract violated the Clayton Act, and therefore, Nashville would not fulfill its conditions, forcing Tampa Electric to purchase coal elsewhere at higher prices. Both the District Court and the Circuit Court of Appeals declared the contract void, but he Supreme Court overturned the Circuit Court decision. The Court ruled that because the challenged contract preempted less than 1 percent of the relevant market, it did not substantially lessen competition. The Tampa Electric decision established a Rule of Reason with regard to requirements contracts and limited the reach of the 1949 Standard Oil precedent. 12 April 2025 18

21.3 Exclusive Dealing Agreements Visa (2003) In 2003, in United States v. Visa USA, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed a district court ruling that Visa and MasterCard had illegally used exclusive dealing arrangements with banks to reduce and eliminate competition from American Express and Discover. Visa and MasterCard work in association with member banks to issue credit cards. The banks are responsible for finding customers and the banks set the terms (annual fees, interest rates, penalties) for the cards. Visa and MasterCard allowed banks to issue both Visa and MasterCard credit cards, but both companies required that any bank that issued an American Express or a Discover card be expelled from their credit card and ATM networks. Therefore, if a Visa or MasterCard bank issued an American Express or Discover card, the bank would be eliminated from the only two worldwide ATM networks Visa s Plus and MasterCard s Cirrus. Because virtually every U.S. bank is a member of the Visa, MasterCard, Plus, or Cirrus network, these policies effectively prevented U.S. banks from issuing American Express or Discover cards. The District Court concluded that Visa s and MasterCard s policies had anticompetitive effects. The Court ordered that the exclusionary rules should be permanently eliminated and the defendants should be prevented from imposing any similar type of restrictions in the future. 12 April 2025 19

21.3 Exclusive Dealing Agreements Visa (2003), continued Deciding the case, under the Rule of Reason, to find a violation of the Sherman Act, the Circuit Court required 1. that Visa and MasterCard had to have market power in a particular market; 2. that Visa s and MasterCard s actions had to have substantial adverse negative effects on competition; 3. that Visa and MasterCard could not provide a procompetitive effect to justify their conduct. As to point (1), the Circuit Court agreed with the District Court that Visa and MasterCard had substantial market power because merchants testified that they could not refuse to accept payment by Visa or MasterCard, even if faced with significant price increases, because of customer preferences. As to point (2), the Circuit Court found [t]he most persuasive evidence for harm to competition is the total exclusion of American Express and Discover from a segment of the market for network services . It is largely undisputed that the exclusionary rules have resulted in the failure of Visa and MasterCard member banks to become issuers of American Express and Discover- branded cards. As to point (3), the Circuit Court rejected all of the procompetitive defenses presented by Visa and MasterCard and concluded that [i]n sum, the defendants have failed to show that the anticompetitive effects of their exclusionary rules are outweighed by procompetitive benefits. As a direct result of this decision, on January 29, 2004, Maryland Bank, National Association (MBNA) announced that it would begin issuing its own American Express cards, and other banks were quick to follow. Antitrust decisions can have almost immediate impacts on market structure. 12 April 2025 20

21.3 Territorial and Customer Restrictions Manufacturers sometimes distribute goods through independent dealers who are required to sell only in certain geographic areas or only to certain customers. Although these territorial restrictions often appear to be anticompetitive because they restrict competition among the manufacturer s dealers, they may have redeeming procompetitive effects. They may enable manufacturers to obtain higher-quality dealers and reduce the costs of providing retailing services. The net effect of territorial restrictions is highly dependent on the market power of the manufacturer and whether the restrictions increase the probability of collusion in either manufacturing or retailing. Territorial restrictions, therefore, require a Rule of Reason approach. 12 April 2025 21

21.3 Territorial and Customer Restrictions White Motor (1963) Before the White Motor decision, the Justice Department had taken the position that territorial restrictions were illegal per se, and based on this position, the Department had negotiated a large number of consent decrees. The White Motor Company manufactured trucks and truck parts that it distributed through dealers who agreed to abide by a territorial restriction in their contract. The restriction specified that dealers would not sell trucks to any individual, firm, or corporation located outside of the dealer s exclusive territory. White Motor defended the contracts on the grounds that they enabled White to compete against larger truck manufacturers. The District Court found for the Justice Department and declared territorial restrictions a per se violation of the Sherman Act, granting a summary judgment for the government, which meant that it refused to even consider the evidence. The Supreme Court overturned the summary judgment and remanded the case to the District Court for a full trial. The Supreme Court ruled that territorial restrictions come within a Rule of Reason because We need to know more than we do about the actual impact of these arrangements on competition to decide whether they have such a pernicious effect on competition and lack any redeeming virtue and therefore should be classified as per se violations of the Sherman Act. A full trial based on the evidence was never held in the White Motor case because White Motor agreed to a consent decree under which it gave up its exclusive dealerships. 12 April 2025 22

21.3 Territorial and Customer Restrictions Sandura (1964) Sandura was a relatively small manufacturer of vinyl floor coverings. Its first vinyl floor covering, Sandran, was initially marketed in 1949 and after a quick sales start soon developed two major problems. Sandran usually began to yellow shortly after installation, and even worse, many of the Sandran vinyls delaminated and broke apart. As a result of these problems, the company was on the verge of bankruptcy. Having established a terrible reputation with its original Sandran, Sandura was unable to obtain quality distributors to market its "New Improved Sandran," even though it had solved its earlier problems. In an effort to attract quality distributors, Sandura offered dealers exclusive territories. After establishing the exclusive territories, Sandura was able to become competitive again, although its market share remained small, never exceeding 5 percent. Moreover, Sandura s share was dwarfed by the "Big 3" of the vinyl floor covering industry: Armstrong, Congoleum, and Pabco, which between them controlled over 75 percent of capacity. The Circuit Court applying the Rule of Reason found that under these circumstances Sandura's territorial restrictions were legal, because distributors, the dealers, and the public would all be better served if Sandura continued to be a competitive force. The competitive impact of Sandura's restrictions was positive because the restrictions enabled Sandura to compete more effectively against the large firms. 12 April 2025 23

21.3 Territorial and Customer Restrictions Three years later, however, the Supreme Court handed down a decision, which if permanently upheld, would have overturned the Sandura decision. Schwinn (1967) In 1951, Schwinn was the leading U.S. manufacturer of bicycles, with a 22.5 percent market share, but in the next decade, Schwinn s share declined to 12.8 percent, and it lost its leadership position to the Murray Ohio Manufacturing Company. Murray sold primarily private label bicycles to Sears, Montgomery Ward, and other large chain retailers. By contrast, Schwinn sold some of its bikes through 22 wholesale distributors, who in turn sold to a large number of independent retailers, but most of Schwinn s bikes were sold directly to retailers on consignment or under the so-called Schwinn Plan. Under the Schwinn Plan, Schwinn shipped its bicycles to retailers but Schwinn maintained legal ownership and paid the retailers a commission on each sale. The case revolved around Schwinn s requirement that its 22 wholesalers sell only to franchised Schwinn dealers located in the wholesaler s exclusive territory. The wholesalers, however, were not restricted to selling only Schwinn bicycles, and many carried other brands. Each franchised Schwinn retailer was authorized to buy from only one wholesaler, and the franchised retailers were forbidden from selling to unfranchised bicycle retailers. 12 April 2025 24

21.3 Territorial and Customer Restrictions Schwinn (1967), continued The Supreme Court drew a careful distinction between cases in which Schwinn sold outright to wholesalers and cases in which it sold on consignment or through the Schwinn Plan. In cases of outright sale, a majority held that it was illegal per se for a manufacturer to restrict its distributors sales territory. In the cases in which Schwinn maintained ownership over the goods, under consignment and the Schwinn Plan, the majority held that Schwinn could impose territorial restrictions under a Rule of Reason interpretation. The legal and economic implications of the Schwinn decision are confusing. The decision was meant to clarify and simplify the law by placing a per se interpretation on most territorial restrictions. However, the Schwinn decision created an incentive for firms to avoid a per se ruling by setting up a consignment system of distribution and then hoping the system would pass a Rule of Reason test in court. From an economic perspective, it is hard to see how the Schwinn Plan was any more or less restrictive than the condemned wholesaler retailer system. In 1977, the Supreme Court came to accept this view and overturned the Schwinn decision. 12 April 2025 25

21.3 Territorial and Customer Restrictions Sylvania (1977) Sylvania manufactured television sets, which before 1962 were marketed through a large number of independent retail stores and company-owned distributors. Prompted by a decline in its market share to between 1 and 2 percent, Sylvania decided to change its distribution system. Sylvania eliminated its wholesale distributors and sold directly to a limited number of franchised dealers. To improve its position vis- -vis the industry leader RCA, which controlled over 60 percent of the market, Sylvania limited the number of franchisees in any given area and permitted its franchisees to sell only from the location(s) approved by Sylvania. The new system was an effort to attract more aggressive and competent retailers, and the strategy worked. Under the new plan, Sylvania s market share increased to 5 percent. Continental TV was a San Francisco-based franchisee of Sylvania, and in 1965, Sylvania decided to franchise another San Francisco dealer, Young Brothers, which was located approximately one mile from Continental TV. Continental TV protested that this violated Sylvania s marketing policy. When Sylvania went ahead and franchised Young Brothers, Continental TV canceled a large Sylvania order, and instead purchased a supply of televisions from one of Sylvania s competitors. At approximately the same time that Sylvania franchised Young Brothers, Continental TV wanted to open another store in Sacramento. 12 April 2025 26

21.3 Territorial and Customer Restrictions Sylvania (1977), continued Sylvania refused to grant Continental TV a franchise in Sacramento because, according to Sylvania, the market was already adequately served by existing franchisees. Continental TV then informed Sylvania that it was going to move some Sylvania televisions from San Francisco to Sacramento and sell them from its Sacramento retail store, regardless of its agreement with Sylvania. Two weeks later Sylvania suddenly reduced Continental TV s credit line from $300,000 to $50,000. In response to the credit reduction, Continental TV withheld payments it owed Sylvania. Sylvania then terminated Continental TV s franchise, and Sylvania s collection agency sued Continental TV in an effort to recover payment for the unpaid Sylvania televisions that were still in Continental TV s possession. A District Court jury trial resulted in a damage award of $1.77 million to Continental TV. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and held that Sylvania s restrictions were less harmful to competition than the restrictions used by Schwinn. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Sylvania, and in the process directly overturned the Schwinn decision and returned to the Rule of Reason interpretation of the White Motor case. 12 April 2025 27

21.3 Territorial and Customer Restrictions Sony (1980) Very few cases after the Sylvania decision resulted in a plaintiff successfully challenging a territorial restriction, but the Sony Case represents one of the rare exceptions. Sony sold dictation equipment through a series of regional dealerships. Before 1975, Sony required its dealers to primarily devote and otherwise concentration its operations in the retail sale of Sony products to dealer s local area. In 1974, Eiberger began selling outside its territory. After complaints were lodged against Eierger by other Sony retailers, Sony changed its warranty system requirements so that any sales made out of a retailer s local area required a mandatory payment of a warranty fee to Sony that was roughly equal to the profits the retailer earned on the sale. Sony argued that it wanted to ensure warranty coverage on all sales. By eliminating all profits on sales in other territories, however, Sony effectively eliminated any such sales. The Court of Appeals affirmed a District Court ruling against Sony. The Court noted that the primary purpose of the warranty fee system was to eliminate intrabrand competition among Sony s retailers, and if Sony wished to ensure warranty coverage, there were far less anticompetitive methods of accomplishing that goal. The present state of the law with regard to territorial restrictions applies the Rule of Reason to all cases, which makes economic sense because territorial restrictions of the type used by Sandura and Sylvania have a positive rather than a negative effect on competition. 12 April 2025 28

21.4 Territorial and Customer Restrictions Sony (1980) Very few cases after the Sylvania decision resulted in a plaintiff successfully challenging a territorial restriction, but the Sony Case represents one of the rare exceptions. Sony sold dictation equipment through a series of regional dealerships. Before 1975, Sony required its dealers to primarily devote and otherwise concentration its operations in the retail sale of Sony products to dealer s local area. In 1974, Eiberger began selling outside its territory. After complaints were lodged against Eierger by other Sony retailers, Sony changed its warranty system requirements so that any sales made out of a retailer s local area required a mandatory payment of a warranty fee to Sony that was roughly equal to the profits the retailer earned on the sale. Sony argued that it wanted to ensure warranty coverage on all sales. By eliminating all profits on sales in other territories, however, Sony effectively eliminated any such sales. The Court of Appeals affirmed a District Court ruling against Sony, noting that the primary purpose of the warranty fee system was to eliminate intrabrand competition among Sony s retailers, and if Sony wished to ensure warranty coverage, there were far less anticompetitive methods of accomplishing that goal. The present state of the law with regard to territorial restrictions applies the Rule of Reason to all cases, which makes economic sense because territorial restrictions of the type used by Sandura and Sylvania have a positive rather than a negative effect on competition. 12 April 2025 29

21.5 Resale Price Maintenance Agreements Resale Price Maintenance (RPM) is the vertical counterpart of horizontal price fixing. Until 2007, the courts had generally been tougher than Congress on RPM agreements, but 2007, the Supreme Court, by a 5-4 decision, overturned an almost 100-year-old precedent when it ruled in the Leegin case that RPM should always be judged under a Rule of Reason rather than being per se illegal. Dr. Miles (1911) Dr. Miles produced proprietary medicines under a group of secret formulas. The drugs were sold to wholesalers and retailers under a written agreement that they would sell at prices set by Dr. Miles. Park & Sons was a wholesaler that refused to sign the price maintenance agreement. Park induced a number of wholesalers, who had signed the agreement, to supply it with Dr. Miles s medicines at cut-rate prices. When Park advertised and sold these drugs to retailers at reduced prices, Dr. Miles sued Park. The Supreme Court ruled that the written agreements violated the Sherman Act. Justice Hughes wrote that Dr. Miles, having sold its product at prices satisfactory to itself, the public is entitled to whatever advantage may be derived from competition in the subsequent traffic. 12 April 2025 30

21.5 Resale Price Maintenance Agreements One of the major determining factors in the Dr. Miles decision was the use of a formal written agreement to maintain prices. Eight years later, the Supreme Court handed down a decision that limited the reach of the Dr. Miles decision to cases in which a written agreement was used to enforce RPM. Colgate (1919) Colgate announced that it would refuse to supply any wholesaler or retailer that did not abide by Colgate s suggested prices, but there was no written agreement. The evidence suggested that Colgate sometimes went beyond simply announcing that it would not deal with price-cutters by using investigations to determine which companies were reducing prices and soliciting information from dealers regarding which of its retailers were reducing prices. The Supreme Court ruled that Colgate s actions did not violate the Sherman Act. According to the Court, the act does not restrict the long recognized right of a trader or manufacturer engaged in an entirely private business, freely to exercise his own independent discretion as to parties with whom he will deal. 12 April 2025 31

21.5 Resale Price Maintenance Agreements The Colgate decision created a large loophole in the Sherman Act with regard to RPM. Within three years of that decision, however, the Supreme Court twice attempted to clarify its meaning. In both United States v. Schrader s Sons and FTC v. Beech Nut Packing Company, the Supreme Court ruled that an express written agreement was not necessary for a RPM agreement to violate the Sherman Act. In both of these cases, the Court ruled that because the defendants had made elaborate arrangements to police their RPM agreements, the plans violated the antitrust laws. These cases limited, without overturning, the Colgate precedent and helped to create a political movement among small retailers to legalize RPM. In 1937, this movement paid off with the passage of the Miller Tydings Act. The Miller Tydings Act amended the Sherman Act to permit states to pass laws legalizing RPM. The act also prevented the FTC from taking action against RPM as an unfair method of competition. By 1941, 45 of the 48 states had passed so-called fair trade laws permitting RPM. Only Texas, Missouri, Vermont, and the District of Columbia stood as exceptions. 12 April 2025 32

21.5 Resale Price Maintenance Agreements Schwegmann (1951) After the Miller Tydings Act gave states the right to permit written RPM agreements, Louisiana passed an RPM law. The Louisiana law went beyond merely permitting RPM agreements; it contained a provision that if one firm signed an RPM agreement, all other retailers in Louisiana were forced to abide by the agreement. When Schwegmann Brothers, a large New Orleans retailer, refused to sign an agreement with Calvert Distillers and continued to sell Calvert liquor at cut-rate prices, Calvert took Schwegmann to court. The Supreme Court sided with Schwegmann and ruled that RPM agreements could not be enforced against non-signers. According to the Court, if the Louisiana law were upheld, then once a distributor executed a contract with a single retailer setting the minimum resale price for a commodity in the state, all other retailers could be forced into line. The Court further stated that if Congress had desired to eliminate the consensual element from RPM it would have added a non-signer provision to the law. Following the Court s lead, Congress voted to overrule the Schwegmann decision in 1952 by passing the McGuire Act, which extended the Miller Tydings Act to include non-signers of an RPM agreement. 12 April 2025 33

21.5 Resale Price Maintenance Agreements Parke Davis (1960) After the passage of the McGuire Act, both Virginia and the District of Columbia failed to enact fair trade laws. Parke Davis, however, announced a national policy of refusing to deal with wholesalers or retailers who sold below its suggested prices. In the summer of 1956, drug retailers in Washington D.C. and Richmond, Virginia, advertised and sold Parke Davis drugs below the RPM prices. To enforce its prices, Parke Davis informed its wholesalers that they would be cut off from supplies if they continued to supply price cutting retailers. Parke Davis also informed each of the cut rate retailers that their supplies would be eliminated if they continued to cut prices. Furthermore, each wholesaler and retailer was informed that every other wholesaler and retailer was being informed of Parke Davis's policy. Even after being threatened by Parke, five retailers refused to abide by Parke Davis's prices, and were then cut off from their supplies by Parke Davis directly and by Parke Davis's wholesalers. Further, supplies of all Parke Davis drugs were eliminated, including prescription drugs that were never sold below RPM prices. When the five retailers persisted in selling drugs from existing stocks below Parke Davis's list prices, Parke Davis decided to modify its policy. Each of the five price cutters was told that shipments would be resumed if they simply stopped advertising Parke Davis drugs at cut rate prices. 12 April 2025 34

21.5 Resale Price Maintenance Agreements Parke Davis (1960), continued When the five price cutters agreed to stop advertising, Parke Davis resumed shipments to all five firms. Within one month, however, several retailers were once again advertising Parke Davis drugs at cut rate prices. By this time the Justice Department, at the request of Dart Drug, had begun an investigation of Parke Davis, and therefore, Parke Davis elected not to take any further legal action. The District Court held that Parke, Davis' actions were legal under the Colgate doctrine. The Supreme Court reversed because Parke Davis had involved the independent wholesalers in its actions and thereby had gone beyond the limits of the Colgate precedent. It was not antitrust policy but economic pressures that ultimately reduced the incidence of RPM. The emergence of large discount chains and the existence of large mail order houses in non fair trade states combined to make the fair trade laws less and less effective. By 1975, only six states had fair trade laws that were enforceable against non- signers, and in 1976 Congress repealed the Miller Tydings and McGuire Acts 12 April 2025 35

21.5 Resale Price Maintenance Agreements Sharp (1988) In 1988, the Supreme Court ruled once again that RPM is not illegal per se, in a case involving Sharp Electronics and two of its dealers in Houston, Texas. In 1968, Sharp had granted Business Electronics an exclusive franchise to market Sharp s electronic calculators (which sold for an average price of approximately $1000 per unit). In 1972, Sharp granted Hartwell a second Houston franchise and published a list of suggested retail prices, which Hartwell generally abided by. Business Electronics consistently maintained prices below the suggested level. In June 1973, Hartwell gave Sharp an ultimatum that it would terminate its relationship with Sharp unless Sharp terminated its relationship with Business Electronics, which Sharp did. A District Court jury found for Business Electronics and awarded $600,000 in damages. The Court of Appeals, however, ordered a new trial because the jury had been given erroneous instructions implying that Sharp s actions could be considered illegal per se. The Supreme Court affirmed the Appeals Court, ordered a new trial, and declared explicitly that vertical restraints including RPM agreements are not to be considered illegal per se unless they include an explicit agreement on price between the manufacturer and the retailer. According to the Sharp decision, as long as the manufacturer avoided a direct agreement regarding what price a retailer will charge, the manufacturer could unilaterally refuse to supply any retailer. 12 April 2025 36

21.5 Resale Price Maintenance Agreements State Oil (1997) In 1968, in Albrecht v. Herald, the Supreme Court ruled that an explicit agreement to set a maximum retail price was illegal per se. In 1997, in State Oil v. Khan, the Supreme Court did something it rarely does: It overruled this case and ruled that an explicit agreement to set a maximum retail price comes under the Rule of Reason. Khan leased a convenience store from State Oil under an agreement to purchase its gasoline from State Oil at a price equal to a suggested retail price set by State Oil, less 3.25 cents per gallon. Kahn was free to charge any price for gasoline but if its price was greater than State Oil s suggested retail price, Kahn had to rebate any additional revenues it collected to State Oil. Khan quickly fell behind on its lease payments to State Oil, and State Oil terminated the agreement and evicted Khan. Kahn then sued State Oil for violating the Sherman Act by preventing Kahn from increasing or decreasing its retail gas prices. According to the complaint, Kahn would have increased its profits if it had been free to charge any price. The District Court found for State Oil, but the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit reversed. The Circuit Court ruled that State Oil s policy was a per se violation under the 1968 precedent in Albrecht v. Herald Co. Despite the fact that the Court of Appeals called the Albrecht precedent unsound when decided, it felt constrained by this precedent. 12 April 2025 37

21.5 Resale Price Maintenance Agreements State Oil (1997), continued Circuit Judge Posner, however, noted that, State Oil might want to place a ceiling on the dealers resale prices in order to prevent them from exploiting that monopoly power fully. [State Oil] would do this not out of disinterested malice, but in its commercial self-interest. The higher the price at which gasoline is resold, the smaller the volume sold, and so the lower the profit to the supplier if the higher profit per gallon at the higher price is being snared by the dealer. Justice O'Connor wrote for a unanimous Supreme Court: After reconsidering Albrecht s rationale and the substantial criticism the decision has received, however, we conclude that there is insufficient economic justification for per se invalidation of vertical maximum price fixing.... In overruling Albrecht, we of course do not hold that all vertical maximum price fixing is per se lawful. Instead, vertical maximum price fixing, like the majority of commercial arrangements subject to the antitrust laws, should be evaluated under the rule of reason. In our view, rule-of-reason analysis will effectively identify those situations in which vertical maximum price fixing amounts to anticompetitive conduct. 12 April 2025 38

21.5 Resale Price Maintenance Agreements Leegin (2007) After declaring in the State Oil case that fixing a maximum price was not illegal per se but came under a Rule of Reason, the Supreme Court in the Leegin case, in 2007, ruled that setting a minimum price also now comes under the Rule of Reason. Leegin manufactures fashion leather goods and accessories under the Brighton label and sells these quality fashion products mostly through independent small boutiques and specialty stores. The case revolved around Leegin s sale of its products to PSKS, which operated Kay s Kloset, a woman s apparel store in Lewisville, Texas. At one time, Brighton was Kay s Kloset s most important product line and accounted for 40 50 percent of Kay s profit. In 1997, Leegin instituted its Brighton Retail Pricing and Promotion Policy, under which Leegin refused to sell its Brighton products to any retailer that sold below its suggested retail prices. Leegin argued that the policy was intended to provide its retailers with sufficient profit margins to provide its customers with service consistent with its retailing strategy. Leegin also contended that discounted price sales would harm the Brighton brand image. 12 April 2025 39

21.5 Resale Price Maintenance Agreements Leegin (2007), continued In December 2002, Leegin discovered that Kay s Kloset had been discounting Brighton s entire line by 20 percent. Kay s Kloset asserted that it had to discount Brighton s line to compete with nearby retailers that were also selling below Leegin s suggested retail prices. Leegin first simply requested that Kay s Kloset stop discounting Brighton products, but Kay s Kloset refused this request. Leegin then cut off Kay s Kloset s supply of Brighton products. As a result of its loss of the Brighton line, Kay s Kloset suffered a decrease in store revenues and PSKS sued Leegin alleging that Leegin had violated the Sherman Act by enter[ing] into agreements with retailers to charge only those prices fixed by Leegin. The District Court, relying on the per se rule established in Dr. Miles, excluded testimony by Leegin s expert witnesses who wanted to explain to the jury the procompetitive effects of Leegin s RPM policy. The jury then found in favor of PSKS and awarded PSKS $1.2 million in damages. The District Court trebled the damages and reimbursed PSKS for its attorney fees and costs, resulting in a judgment against Leegin for $3.975 million. On appeal to the Court of Appeals, Leegin did not refute that it had entered into a vertical price-fixing agreements with its retailers, but instead, contended that the Rule of Reason should have been applied to its behavior. The Appeals Court rejected this argument. 12 April 2025 40

21.5 Resale Price Maintenance Agreements Leegin (2007), continued The Supreme Court reversed and in so doing explicitly overturned the Dr. Miles precedent. The majority ruled that the economics literature is replete with procompetitive justifications for a manufacturer s use of RPM. The Court relied extensively on three economic arguments to justify RPM. 1. RPM can increase interbrand competition by reducing intrabrand competition by encouraging retailers to provide services and promotional efforts that aid the manufacturer, in this case Leegin, to compete against its rivals. 2. The Supreme Court emphasized that RPM can prevent low-priced retailers from free riding on the services provided by high-priced retailers. 3. The Supreme Court noted that RPM can encourage entry by new manufacturers and brands by inducing competent and aggressive retailers to make investments in marketing required to successfully market their new products. In the words of Justice Kennedy writing the opinion for the five-member majority: Notwithstanding the risks of unlawful conduct, it cannot be stated with any degree of confidence that resale price maintenance always or almost always tend[s] to restrict competition and decrease output. Vertical agreements establishing minimum resale prices can have either procompetitive or anticompetitive effects, depending upon the circumstances in which they are formed. And although the empirical evidence on the topic is limited, it does not suggest efficient uses of the agreements are infrequent or hypothetical. For these reasons the Court s decision in Dr. Miles is now overruled. Vertical price restraints are to be judged according to the rule of reason. 12 April 2025 41

21.6 Group Boycotts Group boycotts fall into one of two general categories. In some cases, a group of firms with market power over some product or service draws up a black list, and refuse to deal with firms on the list. In other cases, a group of firms with control over a critical resource draws up a white list, and only supply firms on the list with the resource. If the boycotting group has market power, such boycotts may be anti competitive. Fashion Originator s Guild (1941) The Fashion Originators' Guild of America (FOGA) was an association of designers, manufacturers, and distributors of women's clothing. Guild designers complained that after their original designs entered retail channels, non- Guild members would copy the designs and market virtually identical garments. To stop this piracy, the FOGA combined to force retailers to stop marketing these copied fashions. All guild members agreed not to distribute garments to any retailer who marketed pirated styles. Furthermore, the guild managed to obtain signed agreements from more than 12,000 retailers agreements not to sell pirated clothing. Because the 176 manufacturers who were guild members controlled more than 60 percent of the women's garments that wholesaled at prices above $10.75, these manufacturers had considerable market power in the high priced ($10 was a lot of money for a dress in 1941) segment of the market. 12 April 2025 42

21.6 Group Boycotts Fashion Originator s Guild (1941), continued The FTC filed a complaint under section 5 of the FTC Act, and the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the Guild's actions violated the antitrust laws. The Court made clear that a group boycott could not be justified on the grounds that it was necessary to protect the group from the illegal actions of another firm(s). If the guild was concerned about pirating, it could have filed a law suit against the accused pirates, but it could not take the law into its own hands by violating the Sherman Act. Associated Press (1945) In 1945 the Associated Press (AP) was a cooperative association of more than 1200 newspapers. According to the AP's by laws, members were forbidden from supplying news information to non members, and they were given considerable power to block competitors from becoming AP members. If an applicant for membership did not compete with another AP member, the applicant could become a member by a simple majority vote of the Board of Directors with no financial payment to the AP. 12 April 2025 43

21.6 Group Boycotts Associated Press (1945), continued If an applicant competed with an existing AP member, however, the applicant was required: 1. to pay 10 percent of the "total amount of the regular assessments" received by the AP from members in the same competitive field during the entire period from October 1, 1900 to the time of the new member's election to the AP; 2. to relinquish all exclusive rights to any news or picture service and to make all of its news sources available to its competitors on the same terms as they were available to the applicant; 3. 3 to receive a majority vote of all regular members of the Associated Press. Because the AP was the nation's largest supplier of news stories, these policies made entry into the newspaper business more difficult. Despite the existence of competing news services, the Supreme Court held that the AP's actions violated the Sherman Act. The Court affirmed the District Court's decree and required the AP to furnish news on equal terms to both old and new AP members. The Court also ruled that members were free to furnish news to non members. 12 April 2025 44

21.6 Group Boycotts The Associated Press decision suggested that if a group of firms controls a resource that is considered critical to competition, the group must make the resource available to competitors on a more or less equal basis. It is important to realize, however, that a modified Rule of Reason still applies in group boycott cases. A small group of firms, with no market power that bands together to form a buying or selling cooperative will usually be protected from the antitrust laws as long as alternative sources of supply are readily available to non-members. If the cooperative effort confers a major competitive advantage on co op members, however, the cooperative may have to adopt an open admissions policy. 12 April 2025 45