Instruction-Level Parallelism and Compiler Techniques

Explore software approaches and compiler techniques to enhance instruction-level parallelism (ILP) in computer architecture, including loop unrolling and software pipelining. Learn how dynamic loop unrolling and vector instructions can improve ILP efficiency.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

COMP 740: Computer Architecture and Implementation Montek Singh Mar 18, 2015 Topic: Instruction-Level Parallelism IV (Software Approaches/Compiler Techniques) 1

Outline Motivation Compiler scheduling Loop unrolling Software pipelining 2

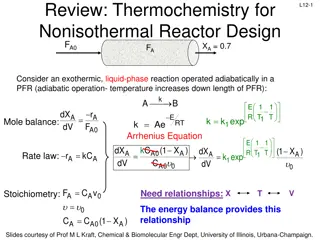

Review: Instruction-Level Parallelism (ILP) Pipelining most effective when: parallelism among instrs 2 instrs are parallel if neither is dependent on the other Problem: parallelism within a basic block is limited branch freq of 15%: implies about 6 instructions in basic block these instructions are likely to depend on each other need to look beyond basic blocks Solution: exploit loop-level parallelism i.e., parallelism across loop iterations to convert loop-level parallelism into ILP, need to unroll the loop dynamically, by the hardware statically, by the compiler using vector instructions: same op applied to all vector elements 3

Motivating Example for Loop Unrolling for (i = 1000; i > 0; i--) x[i] = x[i] + s; LOOP: L.D ADD.D S.D 0(R1), F4 DADDUI BNEZ NOP F0, 0(R1) F4, F0, F2 Assumptions Scalar s is in register F2 Array x starts at memory address 0 1-cycle branch delay No structural hazards R1, R1, -8 R1, LOOP 1 F 2 D - 3 X F 4 M D - 5 W E - 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 L.D ADD.D S.D DADDUI BNEZ NOP L.D E F E D F E X D - M M X F W W M D - W X M W F D X M W 10 cycles per iteration 4

How Far Can We Get With Scheduling? LOOP: L.D DADDUI ADD.D nop BNEZ S.D 8(R1), F4 F0, 0(R1) R1, R1, -8 F4, F0, F2 LOOP: L.D ADD.D S.D 0(R1), F4 DADDUI BNEZ NOP F0, 0(R1) F4, F0, F2 R1, R1, -8 R1, LOOP R1, LOOP 1 F 2 D F 3 X D F 4 M X D F 5 W M E D F 6 7 8 9 10 11 L.D DADDUI ADD.D nop BNEZ S.D W E E E M W D F X D M X W M W 6 cycles per iteration Note change in S.D instruction, from 0(R1) to 8(R1); this is a non-trivial change! 5

Observations on Scheduled Code 3 out of 5 instructions involve FP work The other two constitute loop overhead Could we improve performance by unrolling the loop? assume number of loop iterations is a multiple of 4, and unroll loop body four times in real life, must also handle loop counts that are not multiples of 4 6

Unrolling: Take 1 Even though we have gotten rid of the control dependences, we have data dependences through R1 We could remove data dependences by observing that R1 is decremented by 8 each time Adjust the address specifiers Delete the first three DADDUI s Change the constant in the fourth DADDUI to 32 These are non-trivial inferences for a compiler to make LOOP: L.D ADD.D S.D DADDUI L.D ADD.D S.D DADDUI L.D ADD.D S.D DADDUI L.D ADD.D S.D DADDUI BNEZ NOP F0, 0(R1) F4, F0, F2 0(R1), F4 R1, R1, -8 F0, 0(R1) F4, F0, F2 0(R1), F4 R1, R1, -8 F0, 0(R1) F4, F0, F2 0(R1), F4 R1, R1, -8 F0, 0(R1) F4, F0, F2 0(R1), F4 R1, R1, -8 R1, LOOP 7

Unrolling: Take 2 Performance is now limited by the WAR dependencies on F0 These are name dependences The instructions are not in a producer-consumer relation They are simply using the same registers, but they don t have to We can use different registers in different loop iterations, subject to availability Let s rename registers LOOP: L.D ADD.D S.D L.D ADD.D S.D -8(R1), F4 L.D ADD.D S.D L.D ADD.D S.D DADDUI BNEZ NOP F0, 0(R1) F4, F0, F2 0(R1), F4 F0, -8(R1) F4, F0, F2 F0, -16(R1) F4, F0, F2 -16(R1), F4 F0, -24(R1) F4, F0, F2 -24(R1), F4 R1, R1, -32 R1, LOOP 8

Unrolling: Take 3 Time for execution of 4 iterations 14 instruction cycles 4 L.D ADD.D stalls 8 ADD.D S.D stalls 1 DADDUI BNEZ stall 1 branch delay stall (NOP) 28 cycles for 4 iterations, or 7 cycles per iteration Slower than scheduled version of original loop, which needed 6 cycles per iteration Let s schedule the unrolled loop LOOP: L.D ADD.D S.D L.D ADD.D S.D L.D ADD.D S.D L.D ADD.D S.D DADDUI BNEZ NOP F0, 0(R1) F4, F0, F2 0(R1), F4 F6, -8(R1) F8, F6, F2 -8(R1), F8 F10, -16(R1) F12, F10, F2 -16(R1), F12 F14, -24(R1) F16, F14, F2 -24(R1), F16 R1, R1, -32 R1, LOOP 9

Unrolling: Take 4 LOOP: L.D L.D L.D L.D ADD.D ADD.D ADD.D ADD.D S.D S.D DADDUI S.D BNEZ S.D F0, 0(R1) F6, -8(R1) F10, -16(R1) F14, -24(R1) F4, F0, F2 F8, F6, F2 F12, F10, F2 F16, F14, F2 0(R1), F4 -8(R1), F8 R1, R1, -32 16(R1), F12 R1, LOOP 8(R1), F16 This code runs without stalls 14 cycles for 4 iterations 3.5 cycles per iteration loop control overhead = once every four iterations Note that original loop had three FP instructions that were not independent Loop unrolling exposed independent instructions from multiple loop iterations By unrolling further, can approach asymptotic rate of 3 cycles per instruction Subject to availability of registers 10

What Did The Compiler Have To Do? Determine it was legal to move the S.D after the DADDUI and BNEZ and find the amount to adjust the S.D offset Determine that loop unrolling would be useful by discovering independence of loop iterations Rename registers to avoid name dependences Eliminate extra tests and branches and adjust loop control Determine that L.D s and S.D s can be interchanged by determining that (since R1 is not being updated) the address specifiers 0(R1), -8(R1), -16(R1), -24(R1) all refer to different memory locations Schedule the code, preserving dependences 11

Limits to Gain from Loop Unrolling Benefit of reduction in loop overhead tapers off Amount of overhead amortized diminishes with successive unrolls Code size limitations For larger loops, code size growth is a concern Especially for embedded processors with limited memory Instruction cache miss rate increases Architectural/compiler limitations Register pressure Need many registers to exploit ILP Especially challenging in multiple-issue architectures 12

Dependences Three kinds of dependences Data dependence Name dependence Control dependence In the context of loop-level parallelism, data dependence can be Loop-independent Loop-carried Data dependences act as a limit of how much ILP can be exploited in a compiled program Compiler tries to identify and eliminate dependences Hardware tries to prevent dependences from becoming stalls 13

Control Dependences A control dependence determines the ordering of an instruction with respect to a branch instruction so that the non-branch instruction is executed only when it should be if (p1) {s1;} if (p2) {s2;} Control dependence constrains code motion An instruction that is control dependent on a branch cannot be moved before the branch so that its execution is no longer controlled by the branch An instruction that is not control dependent on a branch cannot be moved after the branch so that its execution is controlled by the branch 14

Data Dependence in Loop Iterations A[u+1] = A[u]+C[u]; B[u+1] = B[u]+A[u+1]; A[u+1] = A[u]+C[u]; B[u+1] = B[u]+A[u+1]; A[u+2] = A[u+1]+C[u+1]; B[u+2] = B[u+1]+A[u+2]; A[u] = A[u]+B[u]; B[u+1] = C[u]+D[u]; A[u] = A[u]+B[u]; B[u+1] = C[u]+D[u]; A[u+1] = A[u+1]+B[u+1]; B[u+2] = C[u+1]+D[u+1]; B[u+1] = C[u]+D[u]; A[u+1] = A[u+1]+B[u+1]; B[u+1] = C[u]+D[u]; A[u+1] = A[u+1]+B[u+1]; B[u+2] = C[u+1]+D[u+1]; A[u+2] = A[u+2]+B[u+2]; 15

Loop Transformation Sometimes loop-carried dependence does not prevent loop parallelization Example: Second loop of previous slide In other cases, loop-carried dependence prohibits loop parallelization Example: First loop of previous slide A[u] = A[u]+B[u]; B[u+1] = C[u]+D[u]; A[u] = A[u]+B[u]; B[u+1] = C[u]+D[u]; A[u+1] = A[u+1]+B[u+1]; B[u+2] = C[u+1]+D[u+1]; A[u+2] = A[u+2]+B[u+2]; B[u+3] = C[u+2]+D[u+2]; A[u] = A[u]+B[u]; B[u+1] = C[u]+D[u]; A[u+1] = A[u+1]+B[u+1]; B[u+2] = C[u+1]+D[u+1]; A[u+2] = A[u+2]+B[u+2]; B[u+3] = C[u+2]+D[u+2]; 16

Software Pipelining Observation If iterations from loops are independent, then we can get ILP by taking instructions from different iterations Software pipelining reorganize loops so that each iteration is made from instructions chosen from different iterations of the original loop i0 i1 Software Pipeline Iteration i2 i3 i4 17

Software Pipelining Example (As in slide 9) Before: Unrolled 3 times 1 L.D F0,0(R1) 2 ADD.D F4,F0,F2 3 S.D 0(R1),F4 4 L.D F0,-8(R1) 5 ADD.D F4,F0,F2 6 S.D -8(R1),F4 7 L.D F0,-16(R1) 8 ADD.D F4,F0,F2 9 S.D -16(R1),F4 10 DADDUI R1,R1,-24 11 BNEZ R1,LOOP After: Software Pipelined L.D F0,0(R1) ADD.D F4,F0,F2 L.D F0,-8(R1) 1 S.D 0(R1),F4; Stores M[i] 2 ADD.D F4,F0,F2; Adds to M[i-1] 3 L.D F0,-16(R1); loads M[i-2] 4 DADDUI R1,R1,-8 5 BNEZ R1,LOOP S.D 0(R1),F4 ADD.D F4,F0,F2 S.D -8(R1),F4 Read F4 Read F0 S.D ADD.D L.D IF ID EX Mem WB IF ID EX Mem WB IF ID EX Mem WB Write F4 Write F0 18

Software Pipelining: Concept A Study of Scalar Compilation Techniques for Pipelined Supercomputers , S. Weiss and J. E. Smith, ISCA 1987, pages 105-109 Notation: Load, Execute, Store Iterations are independent In normal sequence, Ei depends on Li, and Si depends on Ei, leading to pipeline stalls Software pipelining attempts to reduce these delays by inserting other instructions between such dependent pairs and hiding the delay Other instructions are L and S instructions from other loop iterations Does this without consuming extra code space or registers Performance usually not as high as that of loop unrolling How can we permute L, E, S to achieve this? L1 E1 S1 B Loop L2 E2 S2 B Loop L3 E3 S3 B Loop Ln En Sn Loop: Li Ei Si B Loop 19

An Abstract View of Software Pipelining L1 J Entry Loop: Si-1 Entry: Li Ei B Loop Sn Loop: Ei Si Li+1 B Loop En Sn Loop: Li Ei Si B Loop Maintains original L/S order Changes original L/S order L1 J Entry Loop: Si-1 Entry: Ei Li+1 B Loop Sn-1 En Sn L1 L1 J Entry Loop: Li Si-1 Entry: Ei B Loop Sn Loop: Ei Li+1 Si B Loop En Sn 20

Other Compiler Techniques Static Branch Prediction Examples: predict always taken predict never taken predict: forward never taken, backward always taken LD DSUBU R1, R1, R3 BEQZ R1, L OR R4, R5, R6 DADDU R10, R4, R3 DADDU R7, R8, R9 R1, 0(R2) L: Stall needed after LD if branch almost always taken, and R7 not needed in fall-thru move DADDU R7, R8, R9 to right after LD if branch almost never taken, and R4 not needed on taken path move OR instruction to right after LD 21

Very Long Instruction Word (VLIW) VLIW: compiler schedules multiple instructions/issue The long instruction word has room for many operations By definition, all the operations the compiler puts in the long instruction word can execute in parallel E.g., 2 integer operations, 2 FP operations, 2 memory references, 1 branch 16 to 24 bits per field => 7*16 or 112 bits to 7*24 or 168 bits wide Need very sophisticated compiling technique that schedules across several branches 22

Loop Unrolling in VLIW Memory reference 1 Memory reference 2 FP operation 1 FP op. 2 Int. op/ branch Clock LD F0,0(R1) LD F10,-16(R1) LD F14,-24(R1) LD F18,-32(R1) LD F22,-40(R1) ADDD F4,F0,F2 LD F26,-48(R1) SD 0(R1),F4 SD -8(R1),F8 SD -16(R1),F12 SD -24(R1),F16 SD -32(R1),F20 SD -40(R1),F24 SD -0(R1),F28 LD F6,-8(R1) ADDD F8,F6,F2 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ADDD F12,F10,F2 ADDD F16,F14,F2 ADDD F20,F18,F2 ADDD F24,F22,F2 ADDD F28,F26,F2 SUBI R1,R1,#48 BNEZ R1,LOOP Unrolled 7 times to avoid delays 7 results in 9 clocks, or 1.3 clocks/iter (down from 6) Need more registers in VLIW 23