Iran’s Political Culture

Iran's political culture is shaped by various sources of legitimacy, including religious foundations, anti-imperialism, nationalism, and populism. The country's history of foreign interference has influenced a propensity for conspiracy theories. Nationalism drives pride in nuclear development and support for Shiite parties in the region. Populism challenges private enterprise in the industrial sector, reflecting a complex interplay of historical and contemporary forces within Iranian society.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

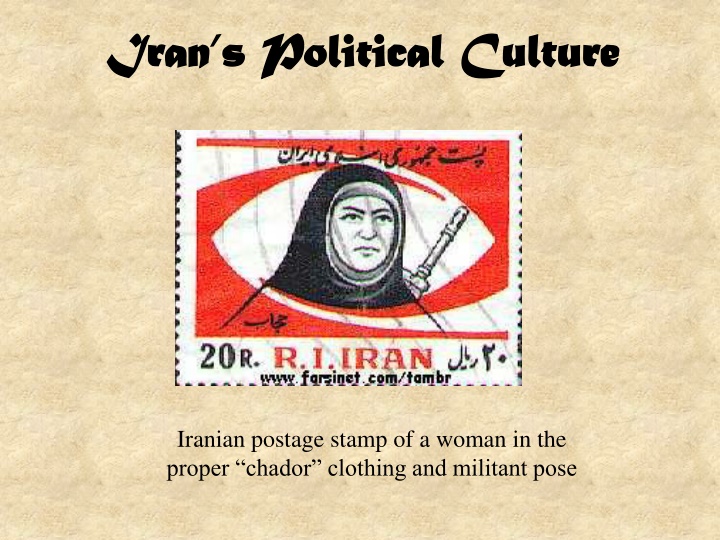

Irans Political Culture Iran s Political Culture Iranian postage stamp of a woman in the proper chador clothing and militant pose

Sources of Legitimacy Within Iranian popular culture we can find support for the regime based on such sources of legitimacy as its religious foundations: the Qur an, Twelver Shiism, clerics, and shari a. Very important sources of legitimacy are the Islamic Revolution and Constitution of 1979 that established the Islamic Republic of Iran. The Constitution, amended in 1989, continues to this day. There are also more secular sources of legitimacy including anti-imperialism, nationalism, populism, and active political participation.

Anti-Imperialism: To a large extent Irans political culture is a result of its place in the international system. Iran survived the age of imperialism as a formally sovereign power, but foreign powers (Britain and Russia) did meddle in Iran s domestic affairs and control of its economy. One result of this outside meddling is that Iranians have a propensity to believe in conspiracies and to interpret politics in terms of conspiracy theories. This was reinforced by actions of the U.S. and Britain in 1953 to back a coup to overthrow Prime Minister Mossadeq.

The main reason for the popularity of the seizure of American hostages at the U.S. Embassy in 1979 was that it symbolically ended the era of foreign interference in Iranian affairs. Nationalism: Iranians are very nationalistic and view themselves as one of the dominant countries of the West rather than as a third world country. This is one reason why they resist calls to abandon nuclear development, as it is viewed as a source of national pride and necessary for defense. Nationalism also leads Iranians to identify themselves as protectors of Iranian style Shiism in the region which translates into support for Shiite parties in Iraq and the Hezbollah in Syria and Lebanon.

Populism: A noteworthy feature of Irans political culture is the suspicion of private enterprise in the industrial sector. Beginning with Reza Shah, the state took a leading role in the development of industry. Under Reza Shah s son, this statism was supplemented by an emerging class of capitalists who benefited by being closely associated with the Shah and his relatives. Islamists and leftists, who carried out the Islamic Revolution, opposed them and their mode of economic development, calling them exploiters. The populism, intensified opposition to conspicuous consumption and large-scale economic activities.

Populist sentiments have not negatively affected rich bazaar merchants, who engage mostly in trade rather than production. However general distrust of industrialists resulted in citizen expectations that the state should be the main purveyors of development and increased living standards. Many expect the state to alleviate poverty and unemployment while others expect the state to provide a positive environment within which individual talent and creativity can flourish. Thus collectivism and individualism are both present in the highly conflictional Iranian society.

Participation in Politics: One indisputable result of the Iranian Revolution was the dramatic increase in the number of citizens who participated in politics. The millions of Iranians who poured into the streets to demand the departure of the Shah in 1978 refused to become mere subjects of a theocratic state. The absence of elections under the Shahs may be one reason for active participation in elections. While Iranians participated in elections since the Islamic Revolution, some boycotted the elections of 2004 and 2005 feeling that the country was becoming less of a republic. The fraudulent election of 2009 had a similar dampening effect.

Political Socialization State sponsored political socialization in Iran has aimed at generating national unity while masking political, ethnic, and socioeconomic cleavages. Iran is really a dual society divided into a traditional, usually poorer, and a modern, usually richer, sector. Under the Pahlavi monarchy, national unity was championed in the mission of creating a modern, industrial, Western society. Under the Islamic Republic, the agenda has changed but the methods of socialization remain similar in the desire to limit input from citizens and to ignore the pluralistic nature of Iranian society.

Education System: The school system was one of the first institutions to be Islamicized by the new regime. School curricula were changed to include substantial religious studies Yearly classes on the Islamic Revolution, and an increased number of mandatory Arabic courses (necessary to read the Qur an). Textbooks were rewritten to provide a sanitized view of a state-sanctioned history of Iran. Children were indoctrinated with chants in praise of Khomeini and anti-American slogans.

The Supreme Council for the Cultural Revolution was appointed by the clerics to review the faculty/curriculum of universities. While this led to faculty dismissals, it also resulted in anti-regime activism on campuses. The Council closed all universities for three years (1980-1983). The regime sponsored the Basij, a paramilitary group reporting to the Pasdaran, to monitor students and faculty, suppress dissent, and mobilize pro-regime activities (with questionable success as many regime critics are in academic circles).

The Military: Military conscription of males has been a fundamental way for creating national unity. The shared experience of basic training and interacting with the military bureaucracy was augmented by the long, bloody war with Iraq. This critical historical juncture affected a large number of Iranian men and their families: over five million served in the armed forces during the 8-year war with over 500,000 casualties. Politically, however, the war was divisive, with part of the ruling establishment questioning why the war was continued after the enemy was driven from Iranian soil in 1982.

Autonomous of the military are the Revolutionary Guards, Pasdaran, who report directly to the Supreme Leader. Religion and Religious Institutions: A 2001 World Value Survey indicated that Iranians are less religious than many countries surveyed with large Muslim populations (ex. Egypt, Nigeria, and Jordan) Religion in Iran has played as much a divisive as unifying role: the Islamic Republic has had difficulty in maintaining unity among clerics as well as within the general society. Religious factions have divided along religious as well as political- economic lines.

Mass Media: The media also plays both a unifying and divisive role in socializing Iranians. Radio and TV are monopolized by the state and are the major means of transmitting official doctrine and mobilizing Iranians for rallies and elections. The head of the Radio and Television Organization is appointed by the Supreme Leader. Access to satellite TV, while illegal, has provided greater diversity for the viewing public. By contrast to the official radio and TV, the printed press has been more diverse with a number of independent newspapers appearing over the years.

During the authoritarian backlash since 2000, the conservative Judiciary clamped down on the more vocal newspapers and journalists, who have turned to the Internet to distribute reports critical of the regime. As an example of the growing power of the internet, Persian is today the fourth most popular language of web bloggers. In the run up to the 2009 presidential elections, the regime ratcheted up control of the press closing down newspapers and raiding the offices of Shirin Ebadi, feminist, human rights lawyer and Nobel Peace activist. Ebadi went into exile, and the regime arrested her sister to intimidate her.

The Family: Whether under the Shah or the Islamic Republic, the home has always been a relatively free place to discuss politics. Patriarchy, in more traditional homes, has limited debate, particularly of religious norms. This is changing, however, as more young Iranians have become the first ones in their families to graduate from secondary schools and universities and are able to be more assertive in their discussion of politics. The subject of politics for Iranian families is not simply dominated by religious considerations. For most, the economy is of greater concern.

Interest Articulation The principle method of interest articulation in Iran is clientelism or patron-client relationships between political figures and citizens. Given the state s access to huge oil revenues over the years, this has translated into Iranian political figures exchanging pledges of political loyalty for access to resources such as subsidies, hard currency, subcontracts, and government jobs. The system of patronage may take on a very direct form with government officials doling out resources to relatives, schoolmates, and people from the same city or province.

The Islamic Republic has distributed subsidies to ensure the loyalty of large portions of the population: for example, it was reported that over $100 billion was being spent per year in public subsidies of fuel, food, medicines, etc. With a 2010 reform plan, fuel subsidies are being cut back in lieu of public assistance that benefit the poor. Elite Recruitment Under the Shah, the small class of educated/secular Iranians who could demonstrate personal loyalty to the monarch, gained access to public offices. Many of the ministers came from land-owning families who attended Western high schools and universities.

Under the Islamic Republic, personalism has played a large role, but in a broader sense. In the early years, political elites came from various backgrounds but the most fundamental credentials were their revolutionary pedigree such as participation in various groups associated with Khomeini. Political elites tended to be younger, less cosmopolitan, and from more middle to lower middle-class backgrounds, often from the provinces. With the Islamicization of the state, more religious clerics were brought into the government, usually trained in seminaries where Khomeini studied.

Non-clerical parliamentarians and ministers began to emerge from educational and military institutions, many having attended Islamicized universities. More recently many elites have come from the ranks of the Basij and Revolutionary Guard, including the former President Ahmadinejad. Kinship ties are a commonly used means to gain political and economic power: Relatives of government officials have used their family ties to gain access to the state. Often these contacts were used as a means for rent-seeking for personal enrichment and advancement. Marriages have also helped cement ties among political elites.