New Testament Epistles and Ancient Epistolography

Explore the similarities and differences between Paul's letters and ancient epistles in terms of opening, body, and closing sections. Discover how Paul Christianized the typical letter closing formula and the unique elements found in his letters.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

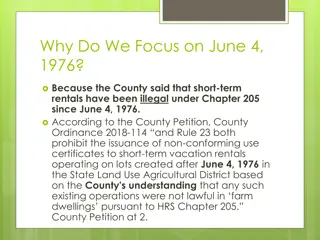

Chapter 10 GOING BY THE LETTER: EPISTLES

CHAPTER OUTLINE The New Testament Epistles and Ancient Epistolography The New Testament Epistles and Rhetorical Criticism The Pauline Epistles The General Epistles General Hermeneutical Issues Sample Exegesis: Romans 7:14 25 Guidelines to Interpreting Epistles

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND ANCIENT Opening The similarities between Paul s letters and ancient epistles are most clearly seen in the opening and closing sections of the letter. Typically, ancient letters opened with: an identification of the sender and the addressee; a salutation or greeting (e.g., Paul to Timothy, greetings ; cf. Acts 15:23; Jas. 1:1); a prayer, which could contain a health wish (cf. 3 John 2) and/or a prayer to the gods on behalf of the addressee.

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND ANCIENT Body Similarities are less recognizable in the body of his letters. While Paul s letters exhibit a considerable degree of diversity, the body of his letters often begins with typical phrases, including: (1) a disclosure formula by which he seeks to inform the addressees about a certain subject I do not want you to be unaware (Rom. 1:13; cf. 2 Cor. 1:18; Phil. 1:12; 1 Thess. 2:1); (2) a request formula which in Philemon is strikingly extended by Greek standards I appeal (parakale ) to you (1 Cor. 1:10; cf. 2 Thess. 2:1); or (3) an expression of astonishment I am astonished that you are so quickly deserting the one who called you (Gal. 1:6).

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND ANCIENT EPISTOLOGRAPHY Closing Paul typically included several items in the closing of his letters, apparently in no particular order, except for the benediction which always came at the end (Romans is an exception). Prayers Commendations of fellow workers Prayer requests Greetings Final instructions and exhortations References to a holy kiss Autographed greetings Grace benediction

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND ANCIENT EPISTOLOGRAPHY Paul Christianized the typical formula for closing a Hellenistic letter of the day with the word farewell (Err sthe or Err so as in Acts 15:29) by using the word charis. Likewise, we do not find in Paul s letters the wish for good health of the recipients which was typical of the Hellenistic letters. Instead, Paul replaced such a wish with a benediction or doxology.

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND ANCIENT EPISTOLOGRAPHY Types of Letters Private and official In his Typoi epistolikoi (Epistolary Types) Demetrius differentiates between 21 types of letters, while Proclus in his Peri epistolimaiou charakteros (Concerning the Epistolary Type) discusses 41 types. First, according to Demetrius (citing Artemon who in turn had edited Aristotle s letter), A letter ought to be written in the same manner as a dialogue, a letter being regarded by him as one of the two sides of a dialogue, Traits of oral presentation are present in his letters and that we get a sense at times that Paul is preaching as if he were with his readers in person.

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND ANCIENT EPISTOLOGRAPHY Types of Letters Second, letters were intended to be expressions of friendship or of one s friendly feelings (pholophronesis). The third feature is that of parousia or presence. Paul likewise wrote letters usually as substitute communication. Finally, fourth, we may identify several specific types of letters that are found in the New Testament. Diatribe Apologetic letter of self-commendation Paraenesis Letter of introduction or commendation

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND ANCIENT EPISTOLOGRAPHY Letter Writing Secretaries or amanuenses Word-by-word dictation; Dictation of the sense of the message, leaving the formulation of the material to the secretary; Instruction of a secretary to write in one s name, without indication of specific contents. Dispatchers or carriers The oral aspect of private letters was present, given several factors such as (1) that greetings at times were to be shared with others; (2) the possibility that the recipient was illiterate and thus the letter needed to be read aloud and before an assembled family, making the arrival of a correspondence a social event; and (3) the fact that letter carriers often waited for a reply before returning to the original writer.

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND ANCIENT EPISTOLOGRAPHY Letter Writing Paul had trusted colleagues (e.g., his co-senders) who carried his letters and were invested with authority from Paul to interpret his letters upon arrival and to read out loud the content of his letters (Eph. 6:21 22; Col. 4:7 8; 1 Thess. 5:27).

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND ANCIENT EPISTOLOGRAPHY Pseudonymityand Allonymity Pseudonymityrefers to a writing in which a later follower attributes his own work to his revered teacher in order to perpetuate that person s teachings and influence. 1 and 2 Timothy Titus

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND ANCIENT EPISTOLOGRAPHY Pseudonymityand Allonymity How is the alleged pseudonymityof the Pastorals or other New Testament epistles supported from first- century usage and practice? First, while pseudonymous writings in other genres (such as Gospels or apocalypses) were not uncommon, pseudonymous letters were exceedingly rare, if not completely unknown. Second, in the apostolic era, far from a prevailing acceptance of pseudonymous epistles, there was actually considerable concern that letters might be forged.

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND ANCIENT EPISTOLOGRAPHY Pseudonymityand Allonymity Allonymityor allepigraphy, a mediating position, which holds that a later author edited what Paul wrote but attributed the writing to Paul or another person without intent to deceive. A better hypothesis is frequently that the author (such as Paul) used an amanuensis, which may account for the distinct vocabulary, a practice attested in his other letters, as we have seen.

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND RHETORICAL CRITICISM Introduction: Rhetorical Species and Proofs Rhetoric, simply stated, is the art of persuasion. Regarding the aim of persuasion, according to classical tradition, a speech falls into one of the three species of rhetoric: forensic, deliberative, and epideictic. Forensic or judicial speech defends or accuses someone regarding past actions by seeking to prove that one s actions were just or unjust. Deliberative speech exhorts or dissuades the audience regarding future actions by seeking to show the expediency or lack thereof of one s future actions. Epideictic discourse affirms communal values by praise or blame in order to affect a present evaluation. Written versus Oral Communication in Antiquity Conclusion

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND RHETORICAL CRITICISM Introduction: Rhetorical Species and Proofs Any orator in ancient times would use three accepted proofs to persuade his audience of a desired end: ethos, pathos, and logos or apodeixis: ethos is the aspect in a speech that establishes the speaker s good character and credibility; pathos refers to the effort of appealing to the emotions of the hearer; logos is the furnishing of clear, persuasive proof, a process of reasoning that moves the argument from what is certain to what the orator seeks to prove.

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND RHETORICAL CRITICISM Written Versus Oral Communication in Antiquity Paul intended his letters to be read out loud to his addressees so that they functioned as long-distance oral communication. This is attested by the functional similarity between 1 Thessalonians 4:9; 5:1; and 1:8c where the verb to speak (lale ) is interchangeable with the verb to write (graph ). This type of reasoning has led to a trend among many New Testament commentary writers to classify each New Testament letter according to the three rhetorical genres and then to outline these using terms from the handbooks on classical rhetoric.

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND RHETORICAL CRITICISM Written Versus Oral Communication in Antiquity In Hans-Dieter Betz s opinion Galatians is an example of forensic rhetoric since Paul seeks to defend his authority and the authority of his gospel. As a result, Betz outlines Galatians as follows: 1. Epistolary Prescript (1:1 5) 2. Exordium (1:6 11) 3. Narratio (1:12 2:14) 4. Propositio (2:15 21) 5. Probatio (3:1 4:31) 6. Exhortatio (5:1 6:10) 7. Epistolary Postscript or Peroratio (6:11 18)

THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES AND RHETORICAL CRITICISM Written Versus Oral Communication in Antiquity There is, however, no agreement on the rhetorical genre into which Galatians (and for that matter, any other Pauline letter) should fit. Apart from the lack of consensus on how we should classify Paul s letters rhetorically, there is also the problem that the assumption of the legitimacy of applying rhetorical criticism to the study of the Pauline letters has no theoretical basis. It was only in the fourth century A.D. (i.e., Julius Victor, Ars Rhetorica 27) that epistolary theory became part of rhetorical theory. The application of rhetorical criticism to the study of Paul s letters and those of the other New Testament writers is of doubtful merit.

THE PAULINE EPISTLES Paul s Use of the Old Testament Paul s letters reflect Old Testament themes, structures, and theology. In fact, one could say that the Old Testament provided the framework and foundation for Paul s theology When studying Paul s quotations of the Old Testament, we must take into consideration the text type that he used: Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek. Of more than 100 quotations, more than 60 of these quotations agree with the Greek version of the Old Testament (i.e., the LXX), though many of these agree with both the LXX and the Hebrew (Masoretic [MT]) text (e.g. Rom. 2:6; 3:4, 13, 18; etc.). Several quotations agree with the LXX, but not with the MT (e.g. Rom. 2:24; 3:14; etc.). A small number agree with the MT and against the LXX (Rom. 1:17; 11:4, 35; etc.). A larger number of others differ from both (e.g. Rom. 3:10 12, 15 17; etc.).

THE PAULINE EPISTLES Paul s Use of the Old Testament 1. What Old Testament text(s) is (are) being cited? Is it just one or a combination? If it is a combination, what is the contribution of each text? 2. Which text type is being followed (Hebrew, Greek, or Aramaic)? What does each version of the citation mean? How does the version that the New Testament has followed contribute to the meaning of the citation? 3. Is the Old Testament citation part of a wider tradition or theology in the Old Testament? If it is, the citation may be alluding to a context much wider than the specific passage from which it has been taken.

THE PAULINE EPISTLES Paul s Use of the Old Testament 4. How did various Jewish and Christian groups and interpreters understand the passage in question? And in what ways does the New Testament citation agree or disagree with the interpretations found in the versions and other ancient exegeses? 5. How does the function of the citation compare to the function of other citations in the New Testament writing under consideration? 6. Finally, what contribution does the citation make to the argument of the New Testament passage in which it is found?

THE PAULINE EPISTLES Paul s Use of the Old Testament The greatest interpretive challenge may be to understand how Paul exegeted a particular Old Testament text or arrived at a certain interpretation of a given passage. Pesher Midrash Qal wahomer Gezerashawah

THE PAULINE EPISTLES Paul s Use of the Christian Traditions: Creeds/Hymns It is usually possible to detect a hymn by the presence of strophes and/or rhythm, which marks the intrusion of poetic style into prose material. In this regard, these passages can be identified as traditional preexistent material, because they contain terminology uncommon to the Pauline letters as well as information that goes beyond the need of the immediate context. Possible example: Philippians 2:6 11

THE PAULINE EPISTLES Paul s Use of the Christian Traditions: Domestic Codes Household codes deal with reciprocal responsibilities between the members of the household: husband/wife; parents/children; and master/slave. The household codes are found in the later letters of Paul (Eph. 5:22 6:9; Col. 3:18 4:1; Titus 2:1 10; cf. Rom. 13:1 7).

THE PAULINE EPISTLES Paul s Use of the Christian Traditions: Slogans The book of 1 Corinthians presents us with yet another example of traditional material: slogans. In the Corinthian correspondence, Paul quotes Corinthian slogans. Possible example: 1 Corinthians 6:12

THE PAULINE EPISTLES Paul s Use of the Christian Traditions: Vice and Virtue Lists The general purpose of including such lists in his letters is to point out the distinctiveness of the Christian community in contrast to the larger pagan society that condoned especially sexual sins. Depravity of unbelievers Encourage believers to avoid the vices and practice the virtues For Timothy to clearly distinguish between true and false teachers Virtues required of church leaders To warn of sinful behavior

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Hebrews The Oral Nature of Hebrews On the one hand, the document was known and circulated in the days of the early church in written form and at the end of the letter the author mentions that he has written to his readers briefly (Heb. 13:22). On the other hand, there are also clear indications of the oral nature of the letter, which may suggest that it originated as a series of sermons that only later was written down and sent as a letter. The author of Hebrews uses stylistic devices such as diatribe and rhythm that reflect the letter s oral character.

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Hebrews The Oral Nature of Hebrews Diatribe is a technique for anticipating objections to an argument, raising them in the form of questions, and then answering them. Rhythm is usually found in poetical compositions, but the author of Hebrews uses it extensively in his writing, thus demonstrating some familiarity with the Hebrew poetry besides the Greco-Roman rhetorical style. In light of all these features, the conclusion is unavoidable that the letter of Hebrews has a distinctively oral character.

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Hebrews The Literary Structure of Hebrews When seeking to determine the outline of the Epistle to the Hebrews, we should keep in mind several prominent topics in the book: the warning passages (i.e., Heb. 2:1 4; 3:7 19; 5:11 6:12; 10:19 39; 12:14 29); Hall of Fame of Heroes of the Faith ; the superiority of Christ; distinction between the doctrinal and the paraenetic or ethical sections of the book; his organization of material and the connection between units is signaled by way of hook-words ; transitional and summarizing elements.

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Hebrews The Literary Structure of Hebrews Introduction: God Has Spoken to Us in a Son (1:1 4) The Son Is Superior (1:5 4:13) The Position of the High Priest in Relation to the Earthly Sacrificial System (4:14 10:25) The Importance of Faith, Perseverance, and Obedience (10:26 13:19) Benediction and Conclusion (13:20 25)

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Hebrews Atypical Feature: The Lack of a Formal Epistolary Frame The conclusion includes the conventional greeting or health wish (13:24) and a final grace benediction (13:25). Moreover, the letter is found among the Pauline corpus in the earliest manuscripts (e.g., in 46between Romans and 1 Corinthians) and has the typical superscript for a letter To the Hebrews like all the other New Testament letters.

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Hebrews Atypical Feature: The Lack of a Formal Epistolary Frame Yet while the composition has an epistolary conclusion, it has no opening salutation. The writer identifies neither himself nor the addressees. He offers no prayer for grace and peace and no expression of thanksgiving or blessing. He starts directly with the proposition to be proven. The lack of the formal epistolary introduction may be due to the fact that the author did not consider it fitting for the high Christological message expressed in the first four verses.

THE GENERAL EPISTLES James The Jewish-Christian Nature of James Doubtless James is a Jewish writing in the sense that it has its roots in Judaism and the Old Testament. OT examples of faith James demonstrates familiarity with some of the concepts of first- century Judaism

THE GENERAL EPISTLES James Evidence for the letter s Christian nature can be gathered also from noting the topical parallelism between James and the other writings of the New Testament: The absolute use of the word onoma ( name ) in 2:7; the self-designation of James as doulos ( servant ); faith (2:14 26) and love (2:8; cf. 1 Thess. 1:2 3; 1 Cor. 13:13; 1 Pet. 1:3 9); eschatological language; thematic parallelism with other New Testament writings; Jesus as a source.

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Jesus as a source believers are to rejoice in trials (1:2; cf. Matt. 5:12); believers are called to be perfect/complete (1:4; cf. Matt. 5:48); believers are encouraged to ask God, for God loves to give (1:5; cf. Matt. 7:7); believers should expect testing and be prepared to endure it, after which they will receive a reward (1:12; cf. Matt. 24:13); believers are not to be angry (1:20; cf. Matt. 5:22);

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Jesus as a source actions are the proof of true faith (2:14; cf. Matt. 7:16 19); the poor are blessed (2:5; cf. Luke 6:20); the rich are warned (2:6 7; cf. Matt. 19:23 24); believers are not to slander (4:11; cf. Matt. 5:22); believers are not to judge (4:12; cf. Matt. 7:1); the humble are praised (3:13; cf. Matt. 5:3).

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Jude and Petrine Epistles The following four hypotheses have been posited for the relationship between Peter and Jude: (1) Peter used Jude; (2) Jude used Peter; (3) both independently used a common source; and (4) common authorship.

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Jude and Petrine Epistles Until the nineteenth century, the predominant view was that Jude used 2 Peter as a source, but more recently a consensus has emerged that 2 Peter used Jude. Most likely, Jude was written prior to 2 Peter and served as a source. This can be illustrated by the way in which these writings use Jewish apocryphal literature.

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Jude and Petrine Epistles The alleged Pseudonymityof 2 Peter Some argue that the language used is un-Petrine Literary genre and date Arguments against pseudonymity First, in spite of the doubts that many early writings express concerning the authenticity of 2 Peter, the ones that accept Petrineauthorship outweigh those that do not. Second, as mentioned in the section on pseudonymity and allonymity, claiming authorship for a letter written by someone else is a deceitful practice and does not comport with the character and message of the biblical writings

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Johannine Epistles The Oral Nature of 1 John Though 1 John demonstrates traits of oral communication, the author states 13 times that he is writing. Thus we are dealing with a literary document. The Structure of 1 John The proposals fall into three categories: a division into two; three; or multiple parts.

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Johannine Epistles The Structure of 1 John Prologue: The Word of Life Witnessed (1:1 4) The Departure of the False Teachers (1:5 2:27) The Proper Conduct of God s Children (2:28 3:24) The Proper Beliefs of God s Children (4:1 5:12) Epilogue: The Confidence of Those Who Walk in God s Light and Love (5:13 21)

THE GENERAL EPISTLES Johannine Epistles Atypical Feature: The Lack of a Formal Epistolary Introduction in 1 John. 2 and 3 John are probably closer to the ancient personal/private letter form than any of Paul s epistles, with the possible exception of Philemon. First John, however, is different. It lacks the opening address and greeting and the closing greeting. Among the New Testament writings, the letter to the Hebrews comes closest to the form of 1 John, since it lacks the formal introduction. Despite the lack of formal epistolary introduction and conclusion, 1 John addresses a specific situation. The question of genre becomes somewhat secondary when we speak of the three Johannine writings jointly.

GENERAL HERMENEUTICAL ISSUES Occasionalityand Normativity One of the basic characteristic of letters is that they are occasional or situational. This means that they were written to address situations and offer solutions to problems related to the author or (most often) to the readers(s). Example: 1 Corinthians 8 10 Faced with such specific situations that are time- and culture-bound, the interpreter has the responsibility to reconstruct as precisely as he can the original situation that gave rise to the problem which Paul addressed by looking into the social, historical, and cultural contexts of Corinthian Christianity.

GENERAL HERMENEUTICAL ISSUES Occasionalityand Normativity Another corollary to the issue of a situation-specific letter is that of constructing a biblical and systematic theology for today. Another aspect of which the interpreter must be aware when trying to determine the normative principle embedded in a text is the distinction between primary and secondary issues in a text.

GENERAL HERMENEUTICAL ISSUES Other Issues in Interpreting Epistles (1) Original Application (2) Specificity of Original Application (3) Broad Principles (4) Contemporary Application With E. D. Hirsch, we contend that we must differentiate between meaning and significance. While the text has one meaning (i.e., the original meaning), this meaning can be applied in different ways depending on the situation.

SAMPLE EXEGESIS: ROMANS 7:14 25 History Literature Theology

GUIDELINES TO INTERPRETING EPISTLES Find out as much as possible about the situation behind the writing of the letter. Corroborate the information found in the text with background information (i.e., historical, social, and cultural setting). Discern the major parts of the letter (introduction, body, and conclusion) and their constitutive elements. Look for the conventional elements that the letter-writer included and left out, especially in the introduction and conclusion. It is in these parts of the letter, especially in the introduction, that we can discern the major problem(s) that occasioned the writing of the letter. 1. 2. 3.

GUIDELINES TO INTERPRETING EPISTLES Determine the structure and argument of the epistle by paying close attention to grammatical, semantic, and rhetorical elements. Above all, it is important for the structure to correspond as closely as possible to the flow of the argument. Interpret each passage in light of the message of the letter as a whole. In other words, always interpret a passage in light of its larger literary context. Seek to discern what is purely occasional and what normative principles can be drawn out from the specific situation the writer is addressing. The normativityof a teaching is usually imbedded in the theological basis for the writer s ethical teaching. 4. 5. 6.