Philosophical Insights from Cavendish and Pascal: Materialism, Self-Movement, and the Limits of Reason

Explore the philosophical perspectives of Margaret Cavendish and Blaise Pascal on materialism, self-movement in nature, sensory perception, knowledge, and the role of reason in understanding the world. Cavendish emphasizes the self-moving nature of all things, while Pascal delves into the limitations of human reason and the significance of religious belief in overcoming skepticism.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

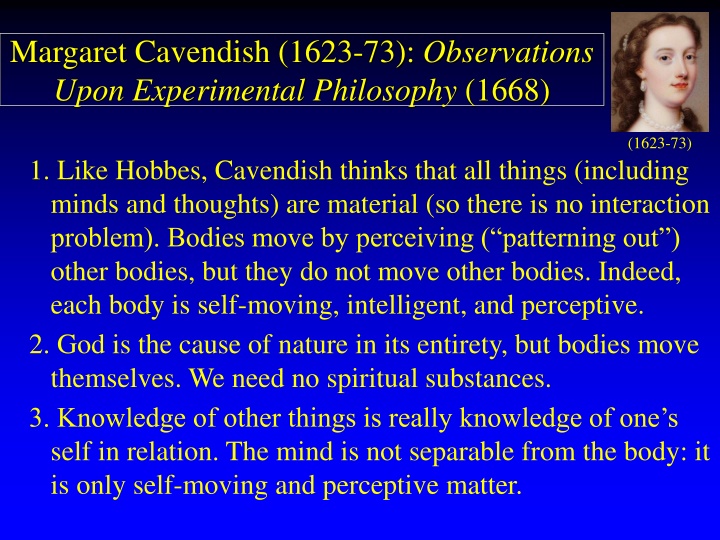

Margaret Cavendish (1623-73): Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy (1668) (1623-73) 1. Like Hobbes, Cavendish thinks that all things (including minds and thoughts) are material (so there is no interaction problem). Bodies move by perceiving ( patterning out ) other bodies, but they do not move other bodies. Indeed, each body is self-moving, intelligent, and perceptive. 2. God is the cause of nature in its entirety, but bodies move themselves. We need no spiritual substances. 3. Knowledge of other things is really knowledge of one s self in relation. The mind is not separable from the body: it is only self-moving and perceptive matter.

Cavendish: Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy 4. The order of nature is due to how parts of nature are self- moving. Unlike Hobbes, Cavendish does not think of nature as purely mechanical, so she says that animals and even material objects like tables can sense and reason. In this way, souls are material. 5. There are three kinds of matter: rational, sensitive, and inanimate. Sensation is not due to the pressure of material bodies on one another, for the sensation would be confused, it would wear out our organs, and it would not explain the orderly (or patterned ) production of things in the world. Sensory perception is sensitivity to particulars.

Cavendish: Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy 6. The motion of matter is eternal. 7. No atom is indivisible (Ch. 31). 8. Knowledge is matter in motion (Ch. 35). No part can subsist apart from all others. All parts of nature are self- moving and self-knowing. They perceive the movement of all other things as expressions of their own movement which we know more or less (as in the case of irregularity). 9. Knowledge is the orderly (interior and exterior, finite and infinite) relation of parts of nature. The perception of exterior objects proceeds from an interior principle of self- knowledge.

Blaise Pascal (1623 1662) Aim: show how Christian revelation cautions against humanistic pride (e.g. reason) but promises redemp- tion from our wretchedness (avoiding skepticism). Prior to knowing anything by using reason (e.g. mathematics, science), we must intuit the principles on which such reasoning is based. Reason cannot establish certainty (a science of humanity ) because principles (e.g. on mind body interaction) cannot be demonstrated: they are known only by the heart.

Pascal: Penses So reason cannot achieve certainty because it cannot provide the principles on which reasoning is based. The human condition is to be pitied because we see too much to deny and too little to be sure. The wager (#233): to get people to move from their indifference to the prospect of religious belief, we must see how it is rational to believe. But the wager is not a rational argument for God s existence or for why people should believe: it is only rational to do so. If we must choose anyway, why not choose in a way that makes us faithful, honest, generous, truthful?

Pascal: Penses The heart has its reasons (#277). By reasons of the heart Pascal means the spontaneous, immediate awareness of (1) the reality of the external world, (2) geometrical principles, (3) moral values, and (4) the existence of God. Faith is not based on reason (#278). We are infinitely between God and nothingness. We know neither extreme, so we are wretched and never satisfied, infinitely transcending ourselves, knowing much more than we really do. We do not pridefully know God, nor do we despair in not knowing (since we have the Redeemer to fall back on). We have some evidence but not enough.

Pierre Bayle (1647-1706) Fideism: true faith cannot be justified by reason. Since we can be deceived by our senses, we cannot rely on them for our knowledge of the world (292). Unlike Pyrrhonists, Bayle does not aim to maintain contradictions but to resolve them (if possible) (293). In regard to morality s dependence on conscience, we must be tolerant. Indeed, we are never justified in forcing someone to act against his or her conscience even if one conscientiously persecuted others for not sharing true beliefs (i.e., beliefs for which one could give rational justification, 294).

Bayle (1647-1706) There is no rational solution to the problem of evil. Every theodicy (i.e., rational attempt to reconcile God s existence and evil) fails (295). Still, we must believe, in accord with revelation and our natural light that God is infinitely perfect. If God created us as good, then how could we have freely sinned? Bayle says that the answer to this question is both above and against reason, so we must rely simply on faith (even if that involves us in insoluble difficulties).