Seamus Heaney Poetry Selection

Explore a selection of iconic poems by Seamus Heaney including "Digging," "Death of a Naturalist," and "Blackberry Picking." Immerse yourself in Heaney's vivid imagery and poignant reflections on nature, family, and the passage of time.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

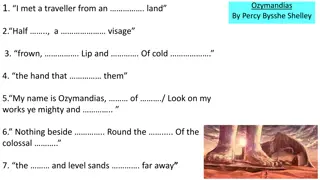

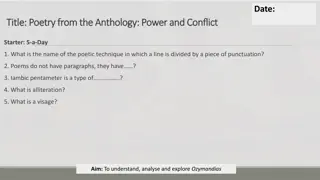

Presentation Transcript

The poetry of Seamus Heaney

Seamus Heaney Anthology Seamus Heaney Anthology 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Oysters 11. The Toome Road 12. Anahorish 13. A Kite for Michael and Christopher 14. Punishment 15. Strange Fruit 16. Postscript 17. At a Potato Digging 18. The Advancement of Learning 19. Early Purges 20. The Forge 21. Requiem for the Croppies Digging Death of a Naturalist Blackberry Picking Storm on an Island Personal Helicon North Station Island Follower The Haw Lantern

Digging Digging Between my finger and my thumb The squat pen rests; snug as a gun. Under my window, a clean rasping sound When the spade sinks into gravelly ground: My father, digging. I look down Till his straining rump among the flowerbeds Bends low, comes up twenty years away Stooping in rhythm through potato drills Where he was digging. The coarse boot nestled on the lug, the shaft Against the inside knee was levered firmly. He rooted out tall tops, buried the bright edge deep To scatter new potatoes that we picked, Loving their cool hardness in our hands. By God, the old man could handle a spade. Just like his old man. My grandfather cut more turf in a day Than any other man on Toner s bog. Once I carried him milk in a bottle Corked sloppily with paper. He straightened up To drink it, then fell to right away Nicking and slicing neatly, heaving sods Over his shoulder, going down and down For the good turf. Digging. The cold smell of potato mould, the squelch and slap Of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge Through living roots awaken in my head. But I ve no spade to follow men like them. Between my finger and my thumb The squat pen rests. I ll dig with it.

Death of a Naturalist Death of a Naturalist All year the flax-am festered in the heart Of the townland; green and heavy-headed Flax had rotted there, weighted down by huge sods. Daily it sweltered in the punishing sun. Bubbles gargled delicately, bluebottles Wove a strong gauze of sound around the smell. There were dragonflies, spotted butterflies, But best of all was the warm thick slobber Of frogspawn that grew like clotted water In the shade of the banks. Here, every spring I would fill jampotfuls of the jellied Specks to range on window sills at home, On shelves at school, and wait and watch until The fattening dots burst, into nimble Swimming tadpoles. Miss Walls would tell us how The daddy frog was called a bullfrog And how he croaked and how the mammy frog Laid hundreds of little eggs and this was Frogspawn. You could tell the weather by frogs too For they were yellow in the sun and brown In rain. Then one hot day when fields were rank With cowdung in the grass the angry frogs Invaded the flax-dam; I ducked through hedges To a coarse croaking that I had not heard Before. The air was thick with a bass chorus. Right down the dam gross bellied frogs were cocked On sods; their loose necks pulsed like snails. Some hopped; The slap and plop were obscene threats. Some sat Poised like mud grenades, their blunt heads farting. I sickened, turned, and ran. The great slime kings Were gathered there for vengeance and I knew That if I dipped my hand the spawn would clutch it.

Blackberry Picking Blackberry Picking Late August, given heavy rain and sun For a full week, the blackberries would ripen. At first, just one, a glossy purple clot Among others, red, green, hard as a knot. You ate that first one and its flesh was sweet Like thickened wine: summer's blood was in it Leaving stains upon the tongue and lust for Picking. Then red ones inked up and that hunger Sent us out with milk cans, pea tins, jam-pots Where briars scratched and wet grass bleached our boots. Round hayfields, cornfields and potato-drills We trekked and picked until the cans were full, Until the tinkling bottom had been covered With green ones, and on top big dark blobs burned Like a plate of eyes. Our hands were peppered With thorn pricks, our palms sticky as Bluebeard's. We hoarded the fresh berries in the byre. But when the bath was filled we found a fur, A rat-grey fungus, glutting on our cache. The juice was stinking too. Once off the bush The fruit fermented, the sweet flesh would turn sour. I always felt like crying. It wasn't fair That all the lovely canfuls smelt of rot. Each year I hoped they'd keep, knew they would not.

Storm on an Island Storm on an Island We are prepared: we build our houses squat, Sink walls in rock and roof them with good slate. This wizened earth has never troubled us With hay, so, as you see, there are no stacks Or stooks that can be lost. Nor are there trees Which might prove company when it blows full Blast: you know what I mean leaves and branches Can raise a tragic chorus in a gale So that you listen to the thing you fear Forgetting that it pummels your house too. But there are no trees, no natural shelter. You might think that the sea is company, Exploding comfortably down on the cliffs But no: when it begins, the flung spray hits The very windows, spits like a tame cat Turned savage. We just sit tight while wind dives And strafes invisibly. Space is a salvo. We are bombarded with the empty air. Strange, it is a huge nothing that we fear.

Personal Helicon Personal Helicon As a child, they could not keep me from wells And old pumps with buckets and windlasses. I loved the dark drop, the trapped sky, the smells Of waterweed, fungus and dank moss. One, in a brickyard, with a rotted board top. I savoured the rich crash when a bucket Plummeted down at the end of a rope. So deep you saw no reflection in it. A shallow one under a dry stone ditch Fructified like any aquarium. When you dragged out long roots from the soft mulch A white face hovered over the bottom. Others had echoes, gave back your own call With a clean new music in it. And one Was scaresome, for there, out of ferns and tall Foxgloves, a rat slapped across my reflection. Now, to pry into roots, to finger slime, To stare, big-eyed Narcissus, into some spring Is beneath all adult dignity. I rhyme To see myself, to set the darkness echoing. .

North North I returned to a long strand, the hammered curve of a bay, and found only the secular powers of the Atlantic thundering. I faced the unmagical invitations of Iceland, the pathetic colonies of Greenland, and suddenly those fabulous raiders, those lying in Orkney and Dublin measured against their long swords rusting, those in the solid belly of stone ships, those hacked and glinting in the gravel of thawed streams were ocean-deafened voices warning me, lifted again in violence and epiphany. The longship s swimming tongue was buoyant with hindsight it said Thor s hammer swung to geography and trade, thick-witted couplings and revenges, the hatreds and behind-backs of the althing, lies and women, exhaustions nominated peace, memory incubating the spilled blood. It said, Lie down in the word-hoard, burrow the coil and gleam of your furrowed brain. Compose in darkness. Expect aurora borealis in the long foray but no cascade of light. Keep your eye clear as the bleb of the icicle, trust the feel of what nubbed treasure your hands have known. .

Station Island Station Island I It was a close grey morning, a reek of early summer pith-life, rotted things, reed-beds, thick young corn hushed and water-blistered. Something beat on iron: a hurry of bell-notes flew over sedge and iris, an escaped ringing that stopped as quickly as it started. Sunday, the silence breathed and could not settle quite for a man appeared at the back of the hedge with a bow-saw, held stiffly up like a lyre. He moved and stopped to gaze at the shins of hazel trees, then angled the saw in, pulled back to gaze again and moved on to the next. I know you, Simon Sweeney, for an old Sabbath breaker that has been dead for years! Damn all you know, he said, his eye still on the hedge and not turning his head. I was your mystery man and am again this morning. Through gaps in the bushes your First Communion face would watch me cutting timber. When cut or broken limbs of trees went yellow, when

woodsmoke sharpened air or ditches rustled you sensed my trail there as if it had been sprayed. It let you half-afraid. When they made you listen in the bedroom dark to wind and rain in the trees and think of tinkers camped under a heeled-up cart you shut your eyes to see a wet axle and spokes in moonlight, and me streaming from the shower, headed for your door. Sunlight broke in the hazels, the quick bell-notes began a second time. I turned at another sound: a crowd of shawled women were wading the young corn, their skirts brushing softly. Their motion saddened morning. It whispered to the silence, Pray for us, pray for us, it conjured through the air until the field was full of half-remembered faces, a loosed congregation that straggled past and on. As I drew behind them I was a fasted pilgrim, light-headed, leaving home to face into my station. Stay clear of that procession he was shouting angrily, Don t turn your back again. Sooner or later, son, you will have to face me with both eyes open.

But the murmur of the crowd, and their feet slushing through the tender bladed growth was another scent picked up, a drugged and open path I was set upon. I trailed those early-risers who had fallen into step before the smokes were up. The quick bell rang again. II I was parked on a high road, listening to peewits and wind blowing round the car when something came to life in the driving mirror, someone walking fast in an overcoat and boots, bareheaded, big, determined in his sure haste along the crown of the road and I somehow felt myself the challenged one. The car door slammed. I was suddenly out face to face with an aggravated man raving on about lying listening for gun-butts to come cracking on the door, yeomen on the rampage, and his neighbor among them, hammering home the shape of things. Round about here you overtook the women, I said, as the thing came clear. Your Lough Derg Pilgrim haunts me every time I cross the mountain as if I am being followed or following. I m on my road there now to do the station. O holy Jesus Christ, does nothing change? His head jerked sharply side to side and up like a diver s surfacing after a plunge, then with a look that said, who is this cub anyhow? he took cognizance again of where he was: the road, the mountain top, and the air, rinsed clear after a shower of rain, worked on his anger visibly until: It is a road you travel on your own. I who learned to read in the reek of flax and smelled hanged bodies rotting on their gibbets and saw their looped slime gleaming from the sacks

hard-mouthed Ribbonmen and Orange bigots made me into the fork-tongued turncoat who mucked the byre of those politics. If times were hard, then I could be hard too. I made the traitor in me sink the knife. And maybe there is a lesson there for you whoever you are, wherever you come out of, for though there s something natural in your smile there s something in it strikes me as defensive. I have no mettle for the angry role, I said, I come from County Derry, born in earshot of an Hibernian Hall where a band of Ribbonmen played hymns to Mary. By then the brotherhood was a frail procession staggering back home drunk on Patrick s Day in collarettes and sashes fringed with green. Obedient strains like theirs tuned me first and not that harp of unforgiving iron the Fenians strung. And a lot of what you wrote I heard and did. This Lough Derg station. Flax-pullings. Dances. Summer crossroads chat. And the shaky local voice of education. All that. And always, Orange drums. And neighbours on the road at night with guns. I know, I know, I know, I know, he said, but you have to try to make sense of what comes. Remember everything and keep your head. The alders in the hedge, I said, mushrooms, dark-clumped grass where cows or horses dunged, the cluck when pith-lined chestnut shells split open in your hand, the melt of shells corrupting, old jampots in a drain clogged up with mud But now Carleton was interrupting: All this is like a trout kept in a spring or maggots sown in wounds for desperate ointment another life that cleans our element. We are earthworms of the earth, and all that has gone through us is what will be our trace. He turned on his heel when he was saying this and headed up the road at the same hard place.

III I got back into the driver s seat. Sunlight moved apple-green over the hill farms, a lough came clear, bog-cotton bowed its wet grey head, dried white and raced the wind that shook the car with its soft buffetings. The airiness of being on high ground lifted me, I let the brake off, ran rumbling downhill without the engine, got into gear and started and began relaxing to the road and the car s rhythms. It was twenty years since I had done the station. Busloads of students after the exams we were a credit, they could be proud of us, those parents who sacrificed, those other dour and threadbare founders in birettas whose faces swam and faded: a road-block swung into view as I took a corner fluently at speed, so that I had to brake and creep past soldiers flattened in the hedge with guns cradled on tripods covering me, up to three halted pigs under camouflage. The tightness and the stillness round that space when the car stops in the road, the troops take in its make and number, and, as one bends his face towards your window, you catch sight of more in a field beyond, hunkering with intent behind black pupils with a perfect bore it has all the pure calm of nightmare, like standing throat-deep in a pool, your head a severed head on a pane of water. Name, sir? Driving license? Destination? The light flotsam of his intonation skimmed past me, like a bit part in Shakespeare, Cockney as Keats or O What a Lovely War. How different were the words home, Christ, ale, master, on his lips and mine! Just step out, sir. Open your boot. And sign this document. Yet why should I fear him less than my own neighbour in the khaki of his Ulster regiment,

his guttural Where are you coming from? feral, staccato and familiar as the muffled drumbeats of a July drum? This island, sir. We ve had a lot to-day heading across there. What s it all about? They re pilgrims. It s a kind of purgatory, I answered. He was handing back the license but shouted to his mates up in the turret of a pig : It s the bible-thumpers we re getting through this area. O.K., you can drive on now, sir. Two riflemen waved their rifles to motion me away, a little emptier, as always, drained bodiless almost, as if their armament and insolence, natural or trained, had flushed out of me everything I was so all that was left was bone I had betrayed and the steering wheel in my obedient paws. But soon it felt like a fictional event, the temper of the voice irrelevant to blowing heather, cloud shadow, bent thorn trees in the roadside, lanes to farms I never entered but without entering knew their dog-barks, chain-clinks, puddles and mildew. To be at one with things. A piled-up cairn, a ploughed field in Ulster white with gulls. I began to roar, I hate where I was born, I hate my neighbour, hate everything that made me biddable and unforthcoming. And so I drove for the border, a goaded shadow.

Follower Follower My father worked with a horse-plough, His shoulders globed like a full sail strung Between the shafts and the furrow. The horses strained at his clicking tongue. An expert. He would set the wing And fit the bright steel-pointed sock. The sod rolled over without breaking. At the headrig, with a single pluck Of reins, the sweating team turned round And back into the land. His eye Narrowed and angled at the ground, Mapping the furrow exactly. I stumbled in his hobnailed wake, Fell sometimes on the polished sod; Sometimes he rode me on his back Dipping and rising to his plod. I wanted to grow up and plough, To close one eye, stiffen my arm. All I ever did was follow In his broad shadow round the farm. I was a nuisance, tripping, falling, Yapping always. But today It is my father who keeps stumbling Behind me, and will not go away

The Haw Lantern The Haw Lantern The wintry haw is burning out of season, crab of the thorn, a small light for small people, wanting no more from them but that they keep the wick of self-respect from dying out, not having to blind them with illumination. But sometimes when your breath plumes in the frost it takes the roaming shape of Diogenes with his lantern, seeking one just man; so you end up scrutinized from behind the haw he holds up at eye-level on its twig, and you flinch before its bonded pith and stone, its blood-prick that you wish would test and clear you, its pecked-at ripeness that scans you, then moves on.

Oysters Oysters Our shells clacked on the plates. My tongue was a filling estuary, My palate hung with starlight: As I tasted the salty Pleiades Orion dipped his foot into the water. Alive and violated, They lay on their bed of ice: Bivalves: the split bulb And philandering sigh of ocean Millions of them ripped and shucked and scattered. We had driven to that coast Through flowers and limestone And there we were, toasting friendship, Laying down a perfect memory In the cool of thatch and crockery. Over the Alps, packed deep in hay and snow, The Romans hauled their oysters south of Rome: I saw damp panniers disgorge The frond-lipped, brine-stung Glut of privilege And was angry that my trust could not repose In the clear light, like poetry or freedom Leaning in from sea. I ate the day Deliberately, that its tang Might quicken me all into verb, pure verb.

The The Toome Toome Road Road One morning early I met armoured cars In convoy, warbling along on powerful tyres, All camouflaged with broken alder branches, And headphoned soldiers standing up in turrets. How long were they approaching down my roads As if they owned them? The whole country was sleeping. I had rights-of-way, fields, cattle in my keeping, Tractors hitched to buckrakes in open sheds, Silos, chill gates, wet slates, the greens and reds Of outhouse roofs. Whom should I run to tell Among all of those with their back doors on the latch For the bringer of bad news, that small-hours visitant Who, by being expected, might be kept distant? Sowers of seed, erectors of headstones O charioteers, above your dormant guns, It stands here still, stands vibrant as you pass, The visible, untoppled omphalos.

Anahorish Anahorish My "place of clear water," the first hill in the world where springs washed into the shiny grass and darkened cobbles in the bed of the lane. Anahorish, soft gradient of consonant, vowel-meadow, after-image of lamps swung through the yards on winter evenings. With pails and barrows those mound-dwellers go waist-deep in mist to break the light ice at wells and dunghills.

A kite for Michael and Christopher A kite for Michael and Christopher All through that Sunday afternoon a kite flew above Sunday, a tightened drumhead, an armful of blown chaff. I'd seen it grey and slippy in the making, I'd tapped it when it dried out white and stiff, I'd tied the bows of newspaper along its six-foot tail. But now it was far up like a small black lark and now it dragged as if the bellied string were a wet rope hauled upon to lift a shoal. My friend says that the human soul is about the weight of a snipe yet the soul at anchor there, the string that sags and ascends, weigh like a furrow assumed into the heavens. Before the kite plunges down into the wood and this line goes useless take in your two hands, boys, and feel the strumming, rooted, long-tailed pull of grief. You were born fit for it. Stand in here in front of me and take the strain.

Punishment Punishment I can feel the tug of the halter at the nape of her neck, the wind on her naked front. It blows her nipples to amber beads, it shakes the frail rigging of her ribs. I can see her drowned body in the bog, the weighing stone, the floating rods and boughs. Under which at first she was a barked sapling that is dug up oak-bone, brain-firkin: her shaved head like a stubble of black corn, her blindfold a soiled bandage, her noose a ring to store the memories of love. Little adulteress, before they punished you you were flaxen-haired, undernourished, and your tar-black face was beautiful. My poor scapegoat, I almost love you but would have cast, I know, the stones of silence. I am the artful voyeur of your brains exposed and darkened combs, your muscles webbing and all your numbered bones: I who have stood dumb when your betraying sisters, cauled in tar, wept by the railings, who would connive in civilized outrage yet understand the exact and tribal, intimate revenge.

Strange Fruit Strange Fruit Here is the girl's head like an exhumed gourd. Oval-faced, prune-skinned, prune-stones for teeth. They unswaddled the wet fern of her hair And made an exhibition of its coil, Let the air at her leathery beauty. Pash of tallow, perishable treasure: Her broken nose is dark as a turf clod, Her eyeholes blank as pools in the old workings. Diodorus Siculus confessed His gradual ease with the likes of this: Murdered, forgotten, nameless, terrible Beheaded girl, outstaring axe And beatification, outstaring What had begun to feel like reverence.

Post Post- -script script And some time make the time to drive out west Into County Clare, along the Flaggy Shore, In September or October, when the wind And the light are working off each other So that the ocean on one side is wild With foam and glitter, and inland among stones The surface of a slate-grey lake is lit By the earthed lightening of flock of swans, Their feathers roughed and ruffling, white on white, Their fully-grown headstrong-looking heads Tucked or cresting or busy underwater. Useless to think you'll park or capture it More thoroughly. You are neither here nor there, A hurry through which known and strange things pass As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways And catch the heart off guard and blow it open

At a Potato Digging At a Potato Digging I. A mechanical digger wrecks the drill, Spins up a dark shower of roots and mould. Labourers swarm in behind, stoop to fill Wicker creels. Fingers go dead in the cold. Like crows attacking crow-black fields, they stretch A higgledy line from hedge to headland; Some pairs keep breaking ragged ranks to fetch A full creel to the pit and straighten, stand Tall for a moment but soon stumble back To fish a new load from the crumbled surf. Heads bow, trunks bend, hands fumble towards the black Mother. Processional stooping through the turf Recurs mindlessly as autumn. Centuries Of fear and homage to the famine god Toughen the muscles behind their humbled knees, Make a seasonal altar of the sod. II. Flint-white, purple. They lie scattered like inflated pebbles. Native to the black hutch of clay where the halved seed shot and clotted these knobbed and slit-eyed tubers seem the petrified hearts of drills. Split by the spade, they show white as cream. Good smells exude from crumbled earth. The rough bark of humus erupts knots of potatoes (a clean birth) whose solid feel, whose wet inside promises taste of ground and root. To be piled in pits; live skulls, blind-eyed. III. Live skulls, blind-eyed, balanced on wild higgledy skeletons scoured the land in forty-five, wolfed the blighted root and died.

The new potato, sound as stone, putrefied when it had lain three days in the long clay pit. Millions rotted along with it. Mouths tightened in, eyes died hard, faces chilled to a plucked bird. In a million wicker huts beaks of famine snipped at guts. A people hungering from birth, grubbing, like plants, in the bitch earth, were grafted with a great sorrow. Hope rotted like a marrow. Stinking potatoes fouled the land, pits turned pus into filthy mounds: and where potato diggers are you still smell the running sore. IV. Under a gay flotilla of gulls The rhythm deadens, the workers stop. Brown bread and tea in bright canfuls Are served for lunch. Dead-beat, they flop Down in the ditch and take their fill Thankfully breaking timeless fasts; Then, stretched on the faithless ground, spill Libations of cold tea, scatter crusts.

The Advancement of Learning The Advancement of Learning I took the embankment path (As always, deferring The bridge). The river nosed past, Pliable, oil-skinned, wearing A transfer of gables and sky. Hunched over the railing, Well away from the road now, I Considered the dirty-keeled swans. Something slobbered curtly, close, Smudging the silence: a rat Slimed out of the water and My throat sickened so quickly that I turned down the path in cold sweat But God, another was nimbling Up the far bank, tracing its wet Arcs on the stones. Incredibly then I established a dreaded Bridgehead. I turned to stare With deliberate, thrilled care At my hitherto snubbed rodent. He clockworked aimlessly a while, Stopped, back bunched and glistening, Ears plastered down on his knobbed skull, Insidiously listening. The tapered tail that followed him, The raindrop eye, the old snout: One by one I took all in. He trained on me. I stared him out Forgetting how I used to panic When his grey brothers scraped and fed Behind the hen-coop in our yard, On ceiling boards above my bed. This terror, cold, wet-furred, small-clawed, Retreated up a pipe for sewage. I stared a minute after him. Then I walked on and crossed the bridge.

Early purges Early purges I was six when I first saw kittens drown. Dan Taggart pitched them, 'the scraggy wee shits', Into a bucket; a frail metal sound, Soft paws scraping like mad. But their tiny din Was soon soused. They were slung on the snout Of the pump and the water pumped in. 'Sure, isn't it better for them now?' Dan said. Like wet gloves they bobbed and shone till he sluiced Them out on the dunghill, glossy and dead. Suddenly frightened, for days I sadly hung Round the yard, watching the three sogged remains Turn mealy and crisp as old summer dung Until I forgot them. But the fear came back When Dan trapped big rats, snared rabbits, shot crows Or, with a sickening tug, pulled old hens' necks. Still, living displaces false sentiments And now, when shrill pups are prodded to drown I just shrug, 'Bloody pups'. It makes sense: 'Prevention of cruelty' talk cuts ice in town Where they consider death unnatural But on well-run farms pests have to be kept down.

The Forge The Forge All I know is a door into the dark. Outside, old axles and iron hoops rusting; Inside, the hammered anvil s short-pitched ring, The unpredictable fantail of sparks Or hiss when a new shoe toughens in water. The anvil must be somewhere in the centre, Horned as a unicorn, at one end and square, Set there immoveable: an altar Where he expends himself in shape and music. Sometimes, leather-aproned, hairs in his nose, He leans out on the jamb, recalls a clatter Of Hoofs where traffic is flashing in rows; Then grunts and goes in, with a slam and flick To beat real iron out, to work the bellows.

Requiem for Croppies Requiem for Croppies The pockets of our greatcoats full of barley... No kitchens on the run, no striking camp... We moved quick and sudden in our own country. The priest lay behind ditches with the tramp. A people hardly marching... on the hike... We found new tactics happening each day: We'd cut through reins and rider with the pike And stampede cattle into infantry, Then retreat through hedges where cavalry must be thrown. Until... on Vinegar Hill... the final conclave. Terraced thousands died, shaking scythes at cannon. The hillside blushed, soaked in our broken wave. They buried us without shroud or coffin And in August... the barley grew up out of our grave.