Software Development Process: From Source Code to Executable

Explore the journey from writing source code to creating an executable program, covering topics such as networking, server architecture, buffer overflows, security risks, and more. Uncover the complexities of software development, from writing binary to utilizing compilers and translators to convert code. Dive into the vulnerabilities and steps involved in the software creation process, highlighting the importance of understanding how source code translates into machine-executable instructions.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

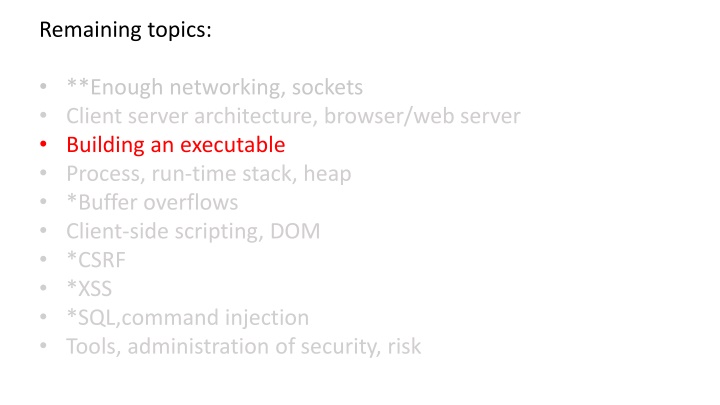

Remaining topics: **Enough networking, sockets Client server architecture, browser/web server Building an executable Process, run-time stack, heap *Buffer overflows Client-side scripting, DOM *CSRF *XSS *SQL,command injection Tools, administration of security, risk

I am hungry If I have enough money and time, I ll go get a pizza hungry = true; if ((I have >= $10) and (I have >= 30 min)) then move(me, pizzeria); else goto (ATM); Source code provides a language we can use to express solutions to problems. The constructs of the language are similar to the way we use language and logic to solve problems. A non-programmer will still feel the code to a degree. The CPU does not understand, and cannot execute source code.

0010001011111101 0000000000000111 1010111101011111 0111110111111110 Executable code can be directly run by the CPU. The 1 s and 0 s in the series of bytes which make up the instructions end up as signals on the internal wiring of the machine

0 0 1 1 1 1 0 O1 O2 O0 R R S S R R S S R S I2 I1 I0 0 0 1

Creating software by writing the binary quickly becomes prohibitively expensive, slow, complicated, error prone impossible

A compiler, or translator, is software which converts one form to another Executable Source code file 0 0101001011 1011101011 1111101001 1001100001 0000000000 0001000101 1010001110 0101010000 1110100001 0000011010 Source code file 1 Compiler Source code file N

There are typically several steps involved, each of which can have its own types of vulnerabilities Source code Macro preprocessor M4 Include/import/platform independence Assembly language Not always this neat linear flow, but all are steps with some differing vulnerabilities g++ Relocatable object, linker, loader Static/dynamic libraries ln ld

What looks like one statement in source code is really several in assembly, and probably even a few more in binary R1 is a piece of hardware called a main() { int i=3, j; mov #3, 8012h mov 8012h, R1 inc R1 mov R1, 8016h r register egister which is where operations on data can happen j = (i + 1); } i lives at the 4 bytes starting at memory location 0x8012 j lives at the 4 bytes starting at memory location 0x8016

By the way, a little about terminology: binary == executable == machine code == a.out all refer to the file produced by the compiler, which holds the successive instructions of the program. The CPU understand and executes these instructions when you run the program ~= program == application == app mostly describes the binary, but sometimes used to mean source + all the other stuff that goes along with the binary

This is the executable the compiler generated The compiler at work This is the source code the programmer wrote $ cc -o myProgram a.c rjoyce9@ITEC-480-E15748 ~/rucsbak $ myProgram hello We now have two files: a.c has the source code; successive bytes are the ASCII values of what you see myProgram has the binary; bytes are machine code

Source code the file name x.c #include <stdio.h> #include <errno.h> int main(argc, argv, envp) int argc; char **argv, **envp; { %d\n , errno); } if (! (f = fopen( file , w ))) { printf( error = } exit(0); # i n c 0x23 0x69 0x6e 0x63 The first four bytes of this file are 0010 0011 0110 1001 0110 1110 0110 0011

binary 0x63 is a lowercase c when interpreted as ASCII, but it is the XRL instruction when interpreted as 8051 machine code

Macro preprocessor Macro preprocessor really the source is 1449 lines: $ cc -E a.c # 1 "a.c" # 1 "<built-in>" # 29 "/usr/include/stdio.h" 3 4 After the macro preprocessor step of the compilation process # 797 "/usr/include/stdio.h" 3 4 # 2 "a.c" int main(argc, argv, envp) int argc; char **argv, **envp; { printf("hello\n"); } (and it still looks like source code)

Assembly language Assembly language $ cc -S a.c rjoyce9@ITEC-480-E15748 ~/rucsbak $ cat a.s .file "a.c" .text .LC0: .ascii "hello\0" .text .globl main .seh_proc main main: pushq %rbp movq %rsp, %rbp subq $32, %rsp movl %ecx, 16(%rbp) movq %rdx, 24(%rbp) movq %r8, 32(%rbp) call __main leaq .LC0(%rip), %rcx call puts movl $0, %eax addq $32, %rsp popq %rbp ret The import/include/ifdef/macros are all gone. Now we have assembly language which is much closer to binary (the gory details will come in a different class)

You get some things for free some useful at compile time: You can use objects or structures and know all their type information to help error check when compiling some useful at runtime: There are some functions you can call, even though you never wrote them

#include <stdio.h> #include <errno.h> int main(argc, argv, envp) int argc; char **argv, **envp; { if (! (f = fopen( file , w ))) { printf( error = %d\n , errno); exit(0); } } From whence comes the variable errno ? How does type- checking happen for the printf function? From whence comes the function printf ?

So, for our purposes, source code import/include for definitions type signatures platform independence bug work-arounds macros clarity/legibility/performance High-level code assembly binary Relocatable object Linking with libraries, static and/or dynamic, libc.a == executable