Theory of Computing TA Times #4 by Hsu, Hung-Wei

Get insights into the Theory of Computing TA Times #4 by Hsu, Hung-Wei providing solutions, statistics, and homework questions related to Turing machines, enumerators, and machine restrictions. Note the caution on relying solely on TA slides for exercise completion.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Theory of Computing TA times #4 Hsu, Hung-Wei 2014/06/04

CAUTION CAUTION Most solutions we showed in TA s slides are more like the ideas rather then completed solutions. You may take them as guides, but shouldn t consider them as everything you need to complete an exercise.

Stats. Homework #8 Average 53.1 Std. Dev. 14.8 Homework #9 Average - Std. Dev. - Homework #10 Average - Std. Dev. -

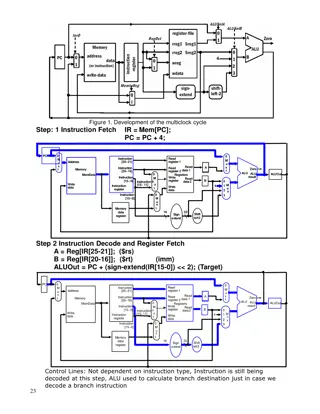

HW#8 Q1 We give the definition of the Turing machine as below. ? = ?, ,?,?,?0,???????,???????, where = 0,1 ,? = {0,1, 0, 1,#, } 0,1, ? 0,1 ? ?4 0 ,? 0 0,? 1 1,? 0 0,? 1 1,? 0,1 ? 0,? ? ?6 ?8 ?0 ?1 ?2 ?3 ?7 0,1 ? 0 0,? 1 1,? 1,? 1 ,? ?5 #,? ? ??????? ??????? 0,1 ? #,?

HW#8 Q2 (1/2) We give an enumerator ? = (?, ,?,?,?0,? ???) as below. ? is a finite set of states. is the output alphabet, not including # . ? is the work tape alphabet. ?:? ? ? ? ?,? {#} work tape ?0 is the initial state. ? ??? is the state that stops ?. printer tape

HW#8 Q2 (2/2) When ? operates on the work tape, it may write something as output on the printer tape, including # , which stands for the separator between output strings. The machine keeps working until it reaches ? ???. So the string on printer tape grows in one direction and looks like: C1#C2#C3# ... For any Cithat occurs in the printer tape, it s the member of the enumerated language.

HW#8* Q4 (1/5) Since outside the read-only part, i.e., input portion, such TM can do everything a normal TM does, the restriction of its power will then lie in the read-only part. The less information you can retrieve from the read-only part, the less power you would have. We will fisrt show that the maximum amount of information that a machine of this type can handle from the read-only part has a upper bound corresponding to the number of states it has. And together with the Myhill-Nerode theorem, we will show that because of the upper bound, such machines can only recognize regular languages. (You can find some details about Myhill-Nerode theorem in the chapter 1 s PROBLEMS section in our textbook.)

HW#8 Q4 (2/5) Input string ? ? Let s say the input string is ? and the rest of the tape is ?. So how much information about ? can the machine carry across the boundary from ? into ?? The machine can cross the boundary between ? and ? several times. Each time machine crosses the boundary moving from right to left, i.e., from ? into ?, it does so in some state, say ?. When it crosses the boundary again moving from left to right (if ever), it comes out from ? in some state, say ?. You would find that no matter when, because of the determinism and the read-only constraint, if the machine ever enters ? in state ? again, it will again come out from ? in state ?. The state ? here is only determined by ? and ?.

HW#8 Q4 (3/5) ? ? Input string Input string Let s write ??? = ? to denote this relationship. And all the possibilities of the relationship can be denote as ??: ? ? { } , where ? is the states of the machine ?; and are used as below. We ve covered most of the cases with ?,?. But we still need to have ?? to denote the state that leads to the first head-out-from-? transition since we don t actually have a state for that. And we writes ??? = if the head never comes out from portion ? again. ? ? Input string Input string Input string Input string

HW#8 Q4 (4/5) Now we ve completed the reasoning of the relationship. We are certain that for any input string ?, it has its own relationship table ??. And no matter what ? does in the ? part, ??is the everything ? can know about ?. On the other hand, if there re two input string, say ? and ?, having a same relationship table for ?, i.e., ??= ??, ? will treat them all the same. The string ? and ? will then be indistinguishable to ?. Note that the possibilities of such ??has an upper bound ( ? + 1)? +1. This indicates that such kind of machines can only distinguish all the possible inputs into a finite set of categories. (In Myhill-Nerode theorem, they re called equivalence classes .)

HW#8 Q4 (5/5) According to Myhill-Nerode theorem, a language has a finite number of equivalent classes iff it is regular. As a language defined by the specialized TM has a finite number of equivalent classes with an upper bound at most ( ? + 1)? +1, corresponding to the state number of TM, the specialized TM can only recognize regular languages.

HW#9 Q2 (1/2) By contradiction, you will find that this problem is telling you that the language consisting of all descriptions of deciders is not Turing- recognizable. We will construct the proof by diagonalization. Since ? is Turing-recognizable, let ??be a enumerator for ?, just as which we had discussed in Theorem 3.21. And let ?1, ?2, , ??, be the strings that ?? generates. We take in lexicographical order, ?1,?2, ,??, . So for each string of , it has its own order number ?.

?1 ?2 ?? HW#9 Q2 (2/2) ?1 Accept Reject Accept ?2 Accept Accept Reject We define the TM ?? as follows. ??= On any input string ?: 1. Compute the order number ? of ?. 2. Use ??to generate the ?th output ??. 3. Simulate ??on ?. 4. If ??accepts, reject; otherwise, accept. As every ?? is a decider, ??is a decider and the language ? is a decidable language. But as the diagonalization we ve showed above, ?? ?, i.e., such ? is not decided by any decider ??that were described in ?. Q.E.D. ?? Reject Accept Reject

HW#9* Q4 (1/3) Firstly, we claim that if there re some inputs that will yield different results when inputted to a DFA ? and another DFA ?, we can find one with its length no more than |?? ??|. We show it as follows. Consider such string ? with its length ? |?? ??|. And let ?1,?2, ,?? and ?1,?2, ,?? be the state sequences went through by ? and ? while computing on the input ?, respectively. Since ? |?? ??|, there must be a pair of statuses ??,??, ??,?? that ??= ??, ??= ??within ?1,?2, ,?? and ?1,?2, ,??. ?? ?? ?? ? ? ? ? ? ?? ?? ??

HW#9 Q4 (2/3) As the figure illustrate in the previous slide, we can cut off the input characters between two points; the results of computations will still be the same. If the length of new string ? is longer than |?? ??|, we can apply the operation again. By keeping on applying the operation, we can certainly find a input string with its length no more than |?? ??| that ? and ? treat differently. After we had figured out a upper bound of finding one such string, we can construct the decider ????? as follows.

HW#9 Q4 (3/3) On input ?,? , where ?,? are both valid DFA: 1. Verify that ? and ? are using the same alphabet set . 2. Calculate |?? ??|. 3. Enumerate all the strings in with length no more than ?? ??, and for each string ?: Simulate ? and ? on ?. If their results are different, reject; otherwise, continue. 4. If all possible ? had been checked, no different result occurs, accept.

HW#9 Q5 This proof is by contradiction. To get the contradiction we assume that ????? is decidable and use this assumption to show that ?????? is decidable. (This proof is similar to that of Theorem 5.4.) If there were a TM ? to decide ?????then we could define a TM ? to decide ??????as follows. ? = On input ? , where ? is a CFG: 1. Run ? on input ?,?1, where G1is a CFG that generates . 2. If ? accepts, accept; if ? rejects, reject. If ? decides ?????, ? decides ??????. But ??????is undecidable by Theorem 5.13, so ?????also must be undecidable.

HW#10 Q2 (1/2) This proof is by reduction from ???. We show that, if ?2???were decidable, ??? would also be. We use the computation history technique in the proof. (The proof is similar to that of Theorem 5.10.) First we explain how can a ?2???validate whether a input computation history is valid. (The way is similar to the way it use to recognize ??????.) The 2??? moves its 1st head to the 1st symbol of the 1st configuration and moves its 2nd head to the right to the 1st symbol of the 2nd configuration. Now, it scans the two heads to the right making sure that the configuration under the right head is a valid successor of the configuration under the left head. The 2??? also notes if the configuration under the right head is an accepting configuration. If it reaches the right-end having seen a valid sequence of configurations with the final one being in an accepting sate for the input machine, it accepts; otherwise, rejects.

HW#10 Q2 (2/2) Now, just like in the Theorem 5.10, after we ve figured out how to build a TM computation history checker using 2??? for an arbitrary TM, we are ready to state the reduction of ??? to ?2???. Suppose that TM ? decides ?2???. Construct TM ? that decides ??? as follows. ? = On input ?,? , where ? is a TM and ? is a string: 1. Construct 2DFA ? from ? and ? as described in the previous slide. 2. Run ? on input ? . 3. If ? rejects, accept; if ? accepts, reject. The rest are similar to that of Theorem 5.10.

HW#10 Q3 Rice s theorem can be described as follows. Let ? be a property (set of languages) that is nontrivial, meaning 1. there exists a Turing machine that recognizes a language in ?, 2. there exists a Turing machine that recognizes a language not in ?. Then, it is undecidable to determine whether the language decided by an arbitrary Turing machine lies in ?. In this problem, we take ? as the set of languages that are recognized by Turing machines and contain 1011 . The rests are left for you.

HW#10 Q4 We show that ? is reducible from ???. Suppose that TM ? decides ?. Construct TM ? that decides ???as follows. ? = On input ?,? , where ? is a TM and ? is a string: 1. Construct a TM ? from ?,? that ? = On any input ?: 1. Put a symbol that isn t in , say # , behind ? (i.e., first blank cell). 2. Write ? on the tape after # . 3. Simulate ? on the ? portion of the tape, and prevent the head from crossing # into the ? portion. 4. If the result of ? is accept, move the head to the ? portion, modify something and accept. 2. Run ? on input ? ,"whatever" . 3. If ? rejects, accept; if ? accepts, reject.

HW#10* Q5 (1/2) ? = entered on any input string. } We now show that ? is reducible from ???, which is known to be undecidable. Assume that ??is a Turing machine that decides ?; we can construct a Turing machine ? that decides ???(details in the next slide). And by thus, we ve showed that ? is undecidable either. ? ? is a Turing machine having a state that will never be

HW#10 Q5 (2/2) ? = On input ?,? : 1. If the input is not a valid representation of a Turing machine and a string, reject. 2. Construct TM ? = Reject any input except ?, and with input ? run ? on it; accept or reject the same as ? does. 3. Modify ? into ? : whenever ? is about to enter the reject state, we make it enter a set of states that lead it to visit every other state first (except for the accept state), and end in the reject state. This can be done by adding a new tape symbol, writing it to two consecutive cells on the tape, and then moving back and forth on them while visiting other states. 4. Run ??on input ? , reject if it accepts; accept otherwise.

1? 1 11 ?1 HW#10 Q7 Accept Reject Accept ?2 Accept Accept Reject We will construct the proof by diagonalization. Since the amount of Turing machines is countable, we can list all the Turing machines in a infinite list in some order, say ?1,?2, . Then we define our diagonalizing language as ? = 1?for those 1? ?(??)}. It s clear that ? is a subset of {1} . And ? is also an undecidable (even more, an unrecognizable) language since there s no Turing machine for recognizing it. ?? Reject Accept Reject