Understanding Capacity and Informed Consent in Mental Health Treatment

Explore the definitions of capacity and informed consent in mental health treatment according to the Mental Health Act 2016. Capacity is defined in terms of understanding and decision-making abilities, while informed consent requires capacity, written consent, and voluntariness. Dive into the treatment criteria for individuals with mental illness who lack capacity to consent, focusing on potential harm or deterioration. Gain valuable insights from expert panels on promoting less restrictive approaches in mental health care.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Insight, Capacity & Less Restrictive Panel: Jacqui Dalling, Dr Sandra Thomson, Michael Bradburn Facilitator: Virginia Ryan For MHRT Member training only March 2020

Panel Facilitator: Virginia Ryan, Deputy President Panel: Jacqui Dalling, Legal Member Dr Sandra Thomson, Medical Member Michael Bradburn, Community Member The next few slides provide some key definitions from the Mental Health Act 2016.

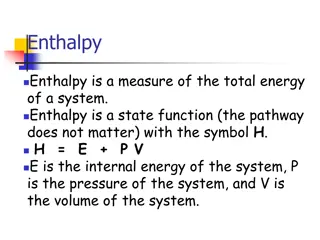

Capacity - Definition Section 14: Meaning of capacity to consent to be treated (1) A person has capacity to consent to be treated if the person: (a) is capable of understanding, in general terms: (i) that the person has an illness, or symptoms of an illness, that affects the person s mental health and wellbeing; (ii) the nature and purpose of the treatment for the illness; (iii) the benefits and risks of the treatment, and alternatives to the treatment; (iv) the consequences of not receiving the treatment; and (b) is capable of making a decision about the treatment and communicating the decision in some way. (2) A person may have capacity to consent to be treated even though the person decides not to receive treatment. (3) A person may be supported by another person in understanding the matters mentioned in subsection (1)(a) and making a decision about the treatment. (4) This section does not affect the common law in relation to: (a) the capacity of a minor to consent to be treated; or (b) a parent of a minor consenting to treatment of the minor.

Informed Consent s233 (1) A person gives informed consent to the person s treatment by regulated treatment only if: (a) the person has capacity to give consent to the treatment; and (b) the consent is in writing signed by the person; and (c) the consent is given freely and voluntarily. (2) For subsection (1)(a), the person has capacity to give consent to the treatment if the person has the ability to: (a) understand the nature and effect of a decision relating to the treatment; and (b) make and communicate the decision. (3) A person can give informed consent in an advance health directive.

Treatment Criteria s12 (1) The treatment criteria for a person are all of the following: (a) the person has a mental illness; (b) the person does not have capacity to consent to be treated for the illness; (c) because of the person s illness, the absence of involuntary treatment, or the absence of continued involuntary treatment, is likely to result in: (i) imminent serious harm to the person or others; or (ii) the person suffering serious mental or physical deterioration. (2) For subsection (1)(b), the person s own consent only is relevant. (3)Subsection (2) applies despite Administration Act 2000, the Powers of Attorney Act 1998 or any other law. the Guardianship and

Less Restrictive Way s13 (1) For this Act, there is a less restrictive way for a person to receive treatment and care for the person s mental illness if, in stead of receiving involuntary treatment and care, the person is able to receive the treatment and care that is reasonably necessary for the person s mental illness in 1 of the following ways: (a) if the person is a minor with the consent of the minor s parent; (b) if the person has made an advance health directive under the advance health directive; (c) if a personal guardian has been appointed for the person with the consent of the personal guardian; (d) if an attorney has been appointed by the person with the consent of the attorney; (e) otherwise with the consent of the person s statutory health attorney.

Less Restrictive Way Cont. (2) In deciding whether there is a less restrictive way for a person to receive the treatment and care that is reasonably necessary for the person s mental illness, a person performing a function or exercising a power under this Act must: (a) consider the ways mentioned in subsection (1) in the listed order set out in the subsection; and (b) comply with the policy that must be made by the chief psychiatrist under s305(1)(a) about when it may not be appropriate for a person to receive treatment and care for the person s mental illness under an advance health directive or with the consent of a personal guardian, attorney or statutory health attorney for the person.

Chief Psychiatrist Policy Treatment Criteria and Assessment of Capacity Having established that the person has a mental illness requiring treatment, a judgement needs to be made in relation to the person s capacity to consent to being treated for that illness. Before treatment can be administered to a person, a clinician must seek the informed consent of the person. Capacity is the ability of that person to give informed consent to a particular treatment at a particular time. The clinician must presume that the patient has capacity to give informed consent to treatment. This presumption of capacity can be rebutted if it can be shown that the patient does not have capacity to give informed consent at the time a particular treatment decision needs to be made. Assessment of capacity is a complex matter. The Act outlines the many different aspects of the person s understanding and appreciation of their illness and treatment that encompasses a full assessment of capacity. All of these elements must be addressed in a capacity assessment. Clinicians must be aware that capacity is specific to the decision that needs to be made at the time (i.e. a person s capacity to consent to treatment is distinct from the person s capacity in relation to managing finances or driving a motor vehicle). Additionally, a person might have the capacity to consent to some aspects of treatment and care but not to others. Clinicians must provide patients with all of the relevant information in making treatment decisions, and must support persons in making all treatment decisions - with the use of interpreters, visual aids, simple language or any other means necessary.

Chief Psychiatrist Policy Treatment Criteria and Assessment of Capacity Cont. Clinicians must ensure the patient has been given a reasonable period of time to consider matters involved in the decision, reasonable opportunity to discuss the decision with the health practitioner, opportunity to seek advice, support and assistance, adequate information on the treatment, alternatives, advantages, disadvantages and beneficial alternative treatments. Clinicians must be aware that a person s capacity to make treatment decisions can fluctuate over time. It is not uncommon for persons with a mental illness to show a fluctuation of mental state throughout the day or over the course of many days. Capacity assessments that are conducted merely on a one-off cross-sectional basis for such patients may not accurately reflect their status. It is important that clinicians recognise persons who have a fluctuating mental state and ensure that, where this applies, capacity assessments are conducted across a number of examinations to ensure that there is stability to the opinion. However, as indicated above, decisions under the Act that relate to capacity must be undertaken at a point in time. The only exception to this is where a clinician is considering revoking a treatment authority (see section 5.4).

Chief Psychiatrist Policy Treatment Criteria and Assessment of Capacity Cont. Clinicians should be cautious of basing an assessment of capacity on impliedconsent . Patients may imply consent by actions such as accepting a tablet into a hand, however, there are limits to implied consent and it should be not be relied on as informed consent. In determining whether capacity is stable, the authorised doctor must consider the nature of the mental illness and the functional approach to the capacity assessment. Where the patient has an established mental illness, and the findings of mental state examinations are consistent over time, repeated capacity assessments must show consistent outcomes (i.e. that the person has capacity at each assessment, to establish that their capacity is stable). For example, most clinical circumstances would require a minimum of two capacity assessments over a period of up to 3- 4 weeks. However, this does not prevent a stable capacity assessment being made in a shorter timeframe if the clinical circumstances warrant it.

Chief Psychiatrist Policy Advance Health Directives and Less Restrictive Way of Treatment Comparison of definitions of capacity Powers of Attorney Act and Guardianship and Administration Act Mental Health Act Capacity, for a person for a matter, means the person is capable of: understanding the nature and effect of decisions about the matter Capacity, to consent to be treated, means the person: is capable of understanding, in general terms: that the person has an illness, or symptoms of an illness, that affects the person s mental health and wellbeing the nature and purpose of the treatment for the illness the benefits and risks of the treatment, and alternatives to the treatment, and the consequences of not receiving the treatment is capable of making a decision about the treatment and communicating the decision in some way. freely and voluntarily making decisions about the matter communicating the decision in some way.

Gillick Competency capacity for minors Minors are presumed not to have capacity to consent to treatment under the common law in Queensland. An English case, known as Gillick, articulated a test for determining a minor s competence to make health care decisions. This has become competence. According to the test, a minor is competent and capable of consenting to their own health care decisions, if they have sufficient understanding and intelligence to allow them to understand the treatment that is proposed. The test requires a treating medical practitioner to consider the level of the minor s understanding in respect of the particular treatment in question. known as Gillick

Gillick Competency capacity for minors Gillick competence is not tied to age, so where one young person may be found competent, a person of similar age may be found incompetent. This would indicate that Gillick competence represents a sliding scale of competence required depending on the type of medical treatment and the competence of the minor based on their intelligence and understanding of the treatment.

Some Resources Queensland Practitioners https://www.qls.com.au/Knowledge_centre/Ethics/Resources/Clie nt_instructions_and_capacity/Queensland_Handbook_for_Practit ioners_on_Legal_Capacity Law Society: on Queensland Legal Handbook for Capacity: Article: Insight and capacity to consent to electroconvulsive therapy by Russ Scott and https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1039856219852290 Response to Article: Decision-making capacity, appreciation and insight in consent by https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1039856219878648 Steve Prowacki, 2019: Christopher Ryan, 2020:

Capacity What is capacity? We have a definition in the Mental Health Act 2016 of capacity to consent to be treated , which is used in the treatment criteria. Where are the nuances? What parts of the definition should we focus on? What is understood by the reference to capacity not being stable in s421(2)? Is there a time period after which capacity might be considered stable ? What is the relationship between stable capacity and an ability to provide consent for treatment and care (e.g. consent for a mental illness may require multiple decisions over a significant period of time)? Is capacity thought of as decision-specific , domain-specific and time-specific ? For example, how is the treatment criteria capacity different to the capacity to dispense with a legal representative?

Insight What evidence is relevant for considering whether a person has capacity? We often hear about insight in the discussion of capacity. Insight: What is insight ? How is insight related to whether a person has capacity? Can someone lack insight and still have capacity? Can someone have insight and lack capacity? When might a person s disagreement with the diagnosis and/or treatment be seen as a legitimate view, as opposed to a view which is evidence of a lack of insight?

Compliance What role does compliance or non-compliance play in determining whether a person has capacity? If, for example, a person refused to take medication due to side-effects what would the Tribunal want to know before determining what bearing that may or may not have on their decision about capacity? Does it make a different if the Tribunal is told that ceasing medication has a great impact on risk?

Questioning We communication and questioning techniques that we should avoid asking leading questions to obtain evidence. What types of questions can we ask to get good evidence from the treating team about capacity when we are getting very limited information? learned in previous masterclasses about

Less Restrictive Way What are some circumstances when the Tribunal might identify a less restrictive way? Presumably this would need to be something that the treating team did not identify themselves or they would have revoked the treatment authority before it coming to the Tribunal for review? When might a person s advance health directive not be the least restrictive way? When might a person s guardian or attorney not be the least restrictive way?

Capacity and Human Rights Section 17(c) of the Human Rights Act protects people from having medical treatment without their full and informed consent. Section 37 provides that everyone has the right to access health services without discrimination. How does an assessment of a person s capacity fit into the Tribunal s human rights considerations?