Understanding Genes and Identity

Explore the relationship between genes and identity, uncovering how genes influence our traits, but other factors such as environment, experiences, and culture also play a significant role in shaping who we are. Delve into topics like behavioral genetics, ethical issues, modern applications of DNA testing, and the broader concept of identity beyond genetics.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Genes and Identity By Assist prof. Dr. Sanaa Jasim Kadhim

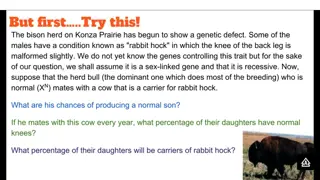

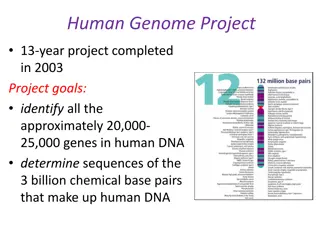

Introduction to Genetics What are genes? Genes are hereditary units found in DNA. They carry instructions for building proteins that determine biological traits. Humans have approximately 20,000 25,000 genes. Heredity: Genes are passed from parents to children and determine features like eye color, height, and blood type.

What is Identity? Identity is the individual's perception of themselves. It includes: - Biological (genetic) identity - Psychological identity (personality, emotions) - Social identity (language, culture, belonging)

Genes and Identity Do genes define our identity completely? Genes influence aspects like: - Introversion or extroversion - Cognitive abilities - Susceptibility to psychological or behavioral disorders Non-genetic factors shaping identity: - Environment: family, education, society - Personal experiences: trauma, success - Culture and history: language, religion, traditions

Behavioral Genetics A field studying genetic effects on behavior. Famous studies: Identical vs. fraternal twins Conclusions: - Genetics contributes to personality, intelligence, and mental disorders. - Environment has a major impact.

Ethical and Philosophical Issues 1. Genetic Determinism: - Belief that genes solely define us. - Risk: Ignoring environment and experience. 2. Genetic Engineering and Identity: - Should parents modify their children's genes? - What is the future of identity in a genetically designed society? 3. Genes and Belonging: - DNA tests reveal ethnic origin. - Do genes define who we are, or does culture and affiliation?

Modern Applications DNA testing for identity: - Used in forensics, paternity tests, and ethnic origins. - Popular companies: AncestryDNA, 23andMe Personalized medicine: - Treatments tailored to the individual's genetic makeup.

Who Are We? Genes are the foundation, but identity is broader. We are the product of genetics, experiences, society, and free will. Understanding the link between genes and identity helps us better understand ourselves and others.

The phrase AncestryDNA advertisement means: Ancestry DNA: One of the most famous companies offering DNA tests to reveal an individual s ethnic and genetic origins. They collect a saliva sample, analyze your DNA, and inform you about your geographical roots (such as European, Middle Eastern, African, etc.) and sometimes suggest familial connections with other people in their database. advertisement = Any promotional material used to attract people to use the service, which may include: Videos, images, social media posts, and phrases such as: Discover your ethnic roots now! Have you ever wondered about your origins? Try Ancestry DNA!

A Brief Explanation of the Key Ideas in the Text: The Advertisement in Question: A man discovers through an AncestryDNA test that he is not German, as he had believed all his life, but rather 52% Irish, Welsh, and Scottish. As a result, he changes his traditional attire from lederhosen to a kilt. The ad is humorous and memorable, but it hides a dangerous idea: That your true identity lies solely in your DNA. Critique of the Central Idea: The author rejects the notion of linking ethnic identity solely to genetic identity, clarifying that: Identity is shaped by cultural, religious, social, and political factors. Genes may tell us about geographic origins, but they do not determine who we truly are. Cultural belonging is not dictated by DNA. Historical and Archaeological Examples: A study of a 6th-century cemetery in Hungary and another in Italy. Despite genetic differences between the two groups, it was cultural identity (such as clothing and burial practices) that marked the distinctions. There were no intermarriages between the two groups, suggesting social or cultural barriers. We cannot claim these individuals were Lombards based on DNA alone; Lombard is a cultural/political term, not a genetic one. Scientific and Philosophical Conclusion: DNA can clarify population movements, but not self-identity or feelings of belonging. No genetic test can tell you: o How you would have defined yourself. o How society would have viewed you. o Or who you believed yourself to be. The Message of the Text: The author is not attacking DNA testing entirely but warns against confusing it with concepts of self-identity and ethnic belonging. Identity is broader and deeper than a genetic analysis.

Genetic Testing: Between Enjoyment and Misunderstanding There s nothing inherently wrong or harmful about doing a genetic ancestry test it can even be fun and insightful. Millions of people who ve taken these tests have enjoyed learning about their supposed ancestral geographic origins. Furthermore, more advanced tests, such as those offered by 23andMe, can screen for predispositions to certain genetic diseases. However, the marketing behind these tests often goes too far, promoting a strong link between geographic origin and ethnic identity. For instance, one online ad declares: Your AncestryDNA results include information about your ethnicity from 26 regions. But does regional identity necessarily equate to ethnic identity?

The Concept of Race: Between Genes and Culture The Greek word ethnos, from which ethnicity is derived, has a long and complex history. In Homer s time, it referred to a group of companions or people who lived and worked together. Later, it came to mean a people or nation, but these terms were always based on cultural and ethical foundations not biological ones. The supposed unity of a people stemmed from: Shared customs Language Laws The belief in a common origin (even if it wasn t true) In many parts of the world, culturally distinct groups live within the same geographic region and preserve their identity through social practices and prohibitions against intermarriage. Over time, however, people cross these boundaries, change identities, merge with other groups, and come to believe in a shared ancestry that binds them.

Does Inheritance Play a Role? Yes, But a Limited One It s true that groups living in the same place and marrying within the group over generations develop distinctive genetic traits. Some of these genetic variations are called alleles, but they often have no impact on appearance or behavior. There are genes that affect: Body structure Hair, eye, and skin color Ability to digest milk or resist diseases But no specific genetic profile determines a person s or a group s identity. Cultural norms determine who is considered a member of a group. And often, political and cultural identity outweighs genetic origin: Genetically similar groups may differ completely in culture. People of different genetic backgrounds may share a strong ethnic identity.

Migration and Mixing: The Rule, Not the Exception Throughout history, identities have never been stable. People have moved due to economic reasons, wars, or disasters. When they integrate with new populations, genetic mixing occurs, and new identity variations emerge. But these new identities reflect not only changes in genes but also: The introduction of new technologies New customs and traditions Different social organizations All of which evolve according to new conditions.

A Research Application: Cemeteries in Hungary and Italy In a recent study with an international team of geneticists, historians, and archaeologists, a 6th- century cemetery in Hungary and another in Italy were examined. The results showed: Two genetically distinct groups: one similar to Central Europeans, the other closer to modern-day Italians. The European group was buried with weapons and jewelry, while the other group had simple burials without personal items. There were no familial ties between the groups indicating no mixed marriages. Can we call them Lombards ? Maybe. But Lombard is a cultural/legal label, not a genetic one. They might have belonged to other tribes (Heruli, Gepids, Suebi...) who were later absorbed under Lombard rule. Even if they saw themselves as Lombards, their religious or linguistic identities could have been different. So the question Who were they really? cannot be answered by DNA alone.

Who Were the Southerners in These Cemeteries? They might have been: Local inhabitants Slaves or servants Farmers But how did they view themselves? As Romans? Italians? Christians or pagans? DNA has no answer for that.

Final Thoughts: What Can Genes Tell Us? And What Can t They? Genetic research is useful for: Understanding population movements Analyzing genetic relationships Revealing some cultural and social patterns But it cannot determine cultural, political, or religious identity. Returning to the man in the AncestryDNAad: Even if he was surprised by his genetic ancestry results, he is no more Scottish than he was German he is simply American, and that is how he is seen in Edinburgh or Munich.

There is also an article by Brian Donovan and Ross Nehm that addresses a sensitive and central issue: How misconceptions about genetics shape social identity and reinforce biases like racism and sexism.

The Main Topic of the Article: The article discusses how genetic education, when presented incorrectly or incompletely, can reinforce what is known as Genetic Essentialism the flawed idea that individuals from the same ethnic or social group share genes that deterministically define their behavior, intelligence, or abilities.

What is Genetic Essentialism? The belief that genes fully explain the differences between groups (racial, gender-based, etc.). It is sometimes used to justify bias, racism, or discrimination against women or people with disabilities. This idea is scientifically inaccurate but implicitly widespread in educational curricula and media.

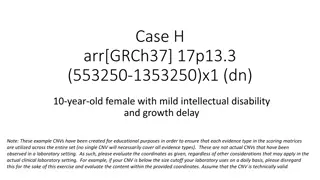

How Does Genetic Education Influence Beliefs? Students who learn that certain diseases are linked to specific races (like sickle cell anemia in Africans) may mistakenly conclude that broader genetic differences exist between races. Education that focuses solely on the biological aspects of sex (such as X and Y chromosomes) may reinforce the belief that males and females are genetically different in intelligence or behavior.

What Do Researchers Suggest? 1. Reform Genetics Curricula to: Clarify that genes interact with environment and culture. o Teach human diversity as continuous, not sharply divided into races. o Highlight the flawed scientific and political history behind the concept of "biological race." o 2. Integrate Social Sciences and Anthropology: To understand that identities (gender, racial, religious...) are socially and culturally constructed, not solely genetic. o Use concepts like cultural relativism and biocultural causation in teaching. o 3. Train Teachers Specifically: Most teachers lack the tools or knowledge to address these concepts. o More research is needed to understand how to support them effectively.

Field Studies from the Special Issue: The article reviews seven research studies, including: An educational intervention that reduced genetic essentialist beliefs among high school students three months after a specialized program. An experiment where students read different texts about sex and gender. Those who read texts stating differences are not genetic were less likely to adopt discriminatory views. A study on the influence of media coverage on behavioral genetics, finding that unbalanced or inaccurate reports can reinforce deterministic ideas.

Real-World Examples Genetics and Identity Example 1: Intelligence and Race in School Textbooks Situation: Some curricula mention diseases like "sickle cell anemia" in Africans or "cystic fibrosis" in Europeans without enough explanation. Result: Students may wrongly conclude there are overarching racial genetic differences, like "Africans are less intelligent" or "Europeans have stronger immunity." Educational Correction: Clarify that: These diseases are related to population history (like malaria), not fixed racial identities. There are no specific genes for intelligence or behavior that fundamentally differ between races.

Example 2: Sex and Gender in Biology Situation: Biology lessons teach that males carry XY and females XX, without addressing the social dimension of gender. Result: Students may believe that all differences between men and women (e.g., leadership ability or emotion) stem from genetics. Educational Response: Include examples of gender diversity (like Turner syndrome or intersex individuals). Emphasize that gender is a social concept that interacts with environment and culture.

Example 3: Ancestry DNA Test Results Situation: A person discovers that 40% of their DNA is Irish, so they change their clothes and habits and say: I m truly Irish! Result: They link identity solely to DNA and ignore cultural and social experience. Scientific Clarification: Genes reflect geographical ancestry, not cultural or national belonging. You may be genetically Middle Eastern but identify as Iraqi, Christian, Kurdish etc.

Example 4: A Classroom Comment Situation: A student says, Men are better at math because they are genetically programmed for it. Traditional Teacher Response: Maybe, there are differences between the sexes Trained Teacher Response: Abilities are learned and influenced by environment. There are leading female mathematicians. Genes don t determine destiny.

Example 5: Media Coverage of Behavioral Genetics Situation: A newspaper article reads: Scientists discover the anger gene in Arab men. Result: This spreads harmful stereotypes based on exaggerated genetic explanations. Educational Response: Teach students to critically read media articles. Educate them on the difference between genetic inheritance and environmental influence.

Background Context: Over the past 20 years, the humanities and social sciences have paid great attention to the concepts of: Identity Self-identification Research Gap: Despite this focus, the influence of genetics on these concepts has not been deeply explored. In other words, the genetic dimension of human identity has been relatively neglected in philosophical and social studies.

What Does This Research Do? First: It distinguishes between multiple types of "identity": 1. Identity as Continuity Over Time: o E.g.: I m the same person I was 10 years ago. 2. Identity as a Basic Kind of Being: o Saying: This is a human, a male, or a female. 3. Identity as a Unique Set of Properties: o Like a DNA fingerprint or a distinctive personality. 4. Identity as a Social Role: o Doctor, mother, Iraqi, Muslim etc. Second: It distinguishes between types of self-identification : 1. Subjective Experience of Identity: o o How does a person feel like themselves? E.g.: I feel like a man, even though my genes are XX. 2. Social Attribution of Identity: o o How does society see and define you? E.g.: Society sees me as male based on appearance.

The Researchers Position on the Genetic Perspective : The researcher believes genetics must be taken seriously when discussing identity. But they also warn against reducing identity solely to genes.

Key Points and Criticisms: 1. The genetic perspective can offer useful information (e.g., ancestry, inherited traits). 2. But it is not enough to understand full identity: It doesn t explain personal experience. o It doesn t define social roles or cultural affiliations. 3. A purely genetic view of identity creates philosophical issues: o It reduces a person to mere genetic makeup. o It ignores the influence of environment, culture, and lived experience. o

Final Aim of the Article: To advocate for integrating genetics with the humanities in understanding human identity. To affirm that identity is a complex phenomenon involving the interaction of genes, mind, society, and history.

Final Note Genetic Identity as a Starting Point: I resemble my parents The author begins with a personal story: people often say he looks like his father or has his mother s eyes. This led him to think that his identity is connected to his genes and parents in appearance, personality, and possibly even future. Core Idea: In everyday life, we often associate genetic identity with our looks, behaviors, and capabilities.

Secondly: The Genetic Blame Game This is how I was made This is how I was made, or It s in my genes to justify: Obesity Mood swings Inability to change But this is a limited way of thinking: Genes provide possibilities, but they do not determine a fixed destiny. Many people use genetics as an excuse:

Thirdly: What about Junk DNA ? In the past, scientists referred to parts of DNA as Junk DNA because they didn t contain clear gene- coding sequences. Now we know that these parts: Regulate gene activity Affect when and where a gene is expressed A deeper analogy: Just as we sometimes view ourselves as broken, we also labeled parts of our DNA as defective while in reality, it s far more complex.

Fourthly: Genes Arent Everything Identical Twins Identical twins have the same DNA, yet: One may develop cancer while the other does not. One may experience a mental illness while the other remains unaffected. Why? Because environment and epigenetic factors play a major role in how genes are used.

Fifthly: The Code Beyond Genes Epigenetics Every cell in the body has the same DNA, but activates different genes (a heart cell a skin cell). This is regulated by chemical tags like DNA methylation. Environment (such as diet, stress, and relationships) triggers these modifications. A beautiful analogy: DNA = A complete library Epigenetic marks = The books we choose to read or ignore

Sixthly: Can We Influence the Identity of Others? Yes. Because we are part of other people s environments. A brilliant scientific example (in mice): Mice that received good maternal care were less stressed and calmer. Mice raised by neglectful mothers were anxious and aggressive. Fascinating: When pups were switched at birth (cross- fostering), the outcomes completely changed. The message: Identity is not just genetic it is shaped by care and environment

Seventhly: Intergenerational Effects Transgenerational Epigenetics Exposure to pesticides in the grandparent generation of mice had measurable effects in grandchildren. Human examples: The Dutch Hunger Winter (1945) impacted the health of the children and grandchildren of pregnant women during that time. In Sweden, the nutrition of grandparents affected disease rates in grandchildren. Conclusion: Your current environment affects your children and grandchildren biologically.

Eighthly: What Does Identity Mean in Light of All This? Identity is not fixed or final. We are created, but we are also in continuous formation. We are not merely the product of our DNA we shape ourselves and others through our daily actions and behaviors. Final message from the author (with a spiritual tone): We are stewards of our own identities and of those around us. If we say, This is just who I am, we may also say, This is all I can ever be and that s dangerous. Instead, we are called to positive transformation and to leave a generational impact on our communities.