Understanding HIV Risk Management Among Incarcerated Men in Kyrgyzstan

Explore how men with opioid use disorder in Kyrgyzstan collectively manage their HIV risk while incarcerated. The study delves into the challenges of HIV transmission among people who inject drugs in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, particularly within prisons. Methods include qualitative interviews with male prisoners to understand attitudes towards health and HIV risk management during incarceration.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

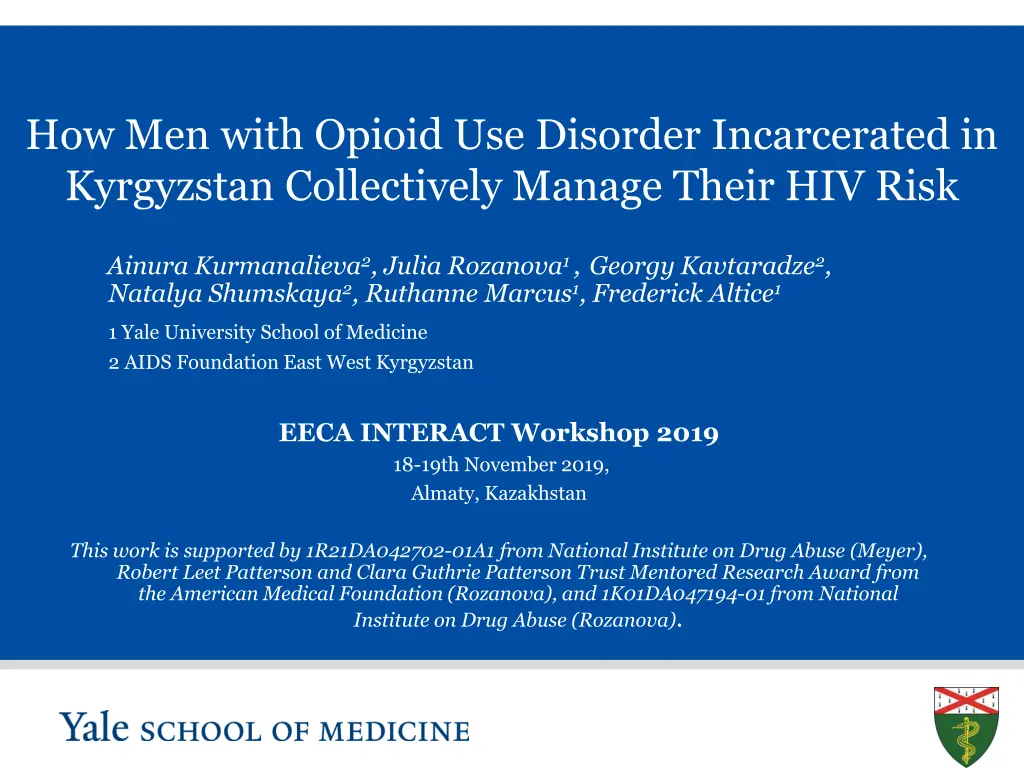

How Men with Opioid Use Disorder Incarcerated in Kyrgyzstan Collectively Manage Their HIV Risk Ainura Kurmanalieva2, Julia Rozanova1 , Georgy Kavtaradze2, Natalya Shumskaya2, Ruthanne Marcus1, Frederick Altice1 1 Yale University School of Medicine 2 AIDS Foundation East West Kyrgyzstan EECA INTERACT Workshop 2019 18-19th November 2019, Almaty, Kazakhstan This work is supported by 1R21DA042702-01A1 from National Institute on Drug Abuse (Meyer), Robert Leet Patterson and Clara Guthrie Patterson Trust Mentored Research Award from the American Medical Foundation (Rozanova), and 1K01DA047194-01 from National Institute on Drug Abuse (Rozanova). S L I D E 0

Setting: Kyrgyzstan S L I D E 1

Research Background Eastern Europe and Central Asia experiences one of the worst HIV epidemics in the world (UNAIDS, 2016). HIV transmission in EECA is largely driven by people who inject drugs (PWID) (UNAIDS, 2016). PWID concentrated within prisons due to criminalization of drug use in EECA. Kyrgyzstan is a lower-middle income country of ~6.2 million people, and has ~10.5 thousand prisoners. Kyrgyzstan s Ministry of Health estimated that HIV prevalence is under 1% among the general population (Ancker et al, 2013). However, HIV prevalence in prisons is ~11.3% (UNAIDS, 2019). In Kyrgyzstan, both methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) and needle-syringe programs (NSP) have been introduced in prisons to reduce HIV transmission Kyrgyz prisons social hierarchy shapes HIV risks (Azbel et al, 2018). PWID prisoners underestimate their HIV risks (Rozanova et al, 2018). S L I D E 2

Methods: ethics, data collection To investigate why there is modest uptake of harm reduction programs in Kyrgyz male prisons, we conducted qualitative interviews with prisoners with a history of drug injection about their attitudes to health and HIV risk management during incarceration. Approvals from Yale HIC, GLORI IRB Kyrgyzstan, and OHRP Purposive sample of ~40 male prisoners in Kyrgyzstan (over 18 years of age, incarcerated in one of the two male prison facilities included into the study, having ever injected opioids based on self-report, and willing and able to provide consent). Qualitative interviews from 2018-2019 (ongoing) Rapport with prisons and prisoners built through several years of collaboration: Provided access to invaluable information Colored the lens through which life in prison is observed Possibly shaped how participants constructed their accounts during interviews S L I D E 3

Methods: data analysis ongoing Interviews are being transcribed verbatim and translated from Russian/Kyrgyz into English English word files imported into Dedoose qualitative data management software Coding the data for both manifest and latent content Analysis of transcribed and translated interview data using the method of constant comparison Refining of emerging themes (latent content) through discussion S L I D E 4

Life in a male prison in Kyrgyzstan S L I D E 5

Methadone dispensary in Kyrgyz prison S L I D E 6

Conceptual framing Prisons as total institutions (Goffman, 1957) Symbolic interactionist approach (Bloomer, Thomas, Redfield): Prison society is constantly re-created through everyday interactions between prisoners What prisoners perceive as real, has real consequences Prison communities as extended primary groups (Anderson, 1976) where people s daily interactions serve to continuously reaffirm and recreate their social status and position (i.e. prison hierarchical culture is a process) S L I D E 7

Hierarchy Among Prisoners (revised from Altice et al, 2018) No drugs to some heroin Gang leader s entourage Regulars Heroin, some MMT Sell-outs MMT, some heroin Pariahs MMT + polysubstance use S L I D E 8

Findings: Collective informal HIV risk management Many prison culture s routine practices are aligned with the public health goals of HIV prevention but challenges persist Prisoners care more about health Popularity of healthy lifestyle; religious proselytization (Muslim); leadership and personal vision of the senior criminal hierarchs Re-emerging drug use stigma may inhibit NSP access especially for Regulars and Pariahs Benign social control to curb HIV risk behaviors Advocacy and folk peer-education within bread-breaking families Benign peer-pressure works better among Regulars than among Sell- Outs and Pariahs Use of MMT by Regulars only endorsed by prison democracy if justified by health need Punitive sanctions in prison code for exposing peers to HIV risks Use of violence for non-disclosing HIV status to injection partners Prohibition of concurrent substance use may cause unsafe injection practices S L I D E 9

Prisoners care more about health We have a gym, many here do exercises. There are people who jog everyday. (Regular) I used to be very athletic, then I started using heroin. It ruined my career in sports. But in [prison #47] I met this [older] guy and he said Look at me I am dying. It is too late for me. But you are very young. You can get off . I take much better care of me now, I haven t injected once since July 2017. I pray, I read a lot of books. I find something useful to do every day. (Regular) They [leader s entourage] don t like to go to NSP, they send shpana [homeboys] to bring them syringes. And the regulars volunteer will get syringes for their barrack. (Pariah) I do work for the healthcare [unit], I always get syringes. Anytime. No problem there. (Sell-out) S L I D E 10

Benign social control to curb HIV risk behaviors P: In our semejnik [bread-breaking family] we have one MMT user, one drug user, one religious guy, one guy has HIV. One guy had TB was recently released. I: So, people who have HIV don t live separately? Or those on MMT? P: No, no, no. We have rules, you must [maintain] hygiene, clean syringes, don t take other guy s razor. You have HIV - no problem, just tell us and nobody will bother you. I: Are you the head of your semejnik then? P: These guys look up to me. I ve been here 20 years. They come to me. To ask my advice. (Regular) S L I D E 11

Punitive sanctions for exposing peers to HIV risks Some scoundrels won t say that they have HIV and shoot up with the rest [during the heroin party in prison]. He leaves his syringe and somebody picks it up. He infects. They get beaten up very bad. (Regular) Only those on methadone are not allowed to exchange syringes. Well, that s how it is here. Except for those on methadone. (Regular) They do not say that they take it for Dimedrol, they say something else. It is prohibited. But they will give syringes for medicines. (Pariah) S L I D E 12

Discussion First study to explore HIV risk management in the context of available HIV prevention programs in prisons Appreciation for prisoners understandings and practices of HIV risk management is essential for public health interventions Emerging norms and values of prison informal culture seem to be largely aligned with HIV prevention goals The renewed drug use stigma may inhibit access to HIV prevention Need to better understand the processes of social control within the prisoner community, including semeiniki (bread-breaking families) Opportune moment for HIV prevention, especially peer-driven interventions julia.rozanova@yale.edu S L I D E 13

Possible Mechanisms -Increases exposure to drugs - Social stigma and marginalization drives risk underground and not amenable to prevention and treatment services Prison Risk Environment Macro Factors Micro Factors -Geographical location in relation to heroin sources -Locations of MMT distribution and NSP services Physical -Exclusion from social participation and meaningful social roles -Social norms & networks of PWID Social Decision to utilize MMT -Economically and socially disempowered populations concentrated within prison -Within prison drug trade (heroin or dimedrol) Economic Opportunities for Prevention & Intervention -Interventions with police; introduction of alternatives to incarceration (drug courts, probation, parole) -Registration requirement -Availability of OAT, NSP Policy -Peer-Driven Interventions to promote uptake of HIV prevention in prisons -Distribution of MMT/NSP in a location amenable to prisoner access S L I D E 14