Understanding Reactive Attachment Disorder and Attachment Styles in Children

Explore the overview of Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) and its implications for school counselors, covering the history of the disorder, diagnostic criteria, risk factors, characteristics, assessment, treatment, and attachment theories. Learn about attachment styles such as secure, avoidant, resistant, and disorganized/disoriented, which impact children's behaviors and relationships in different ways.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Reactive Attachment Disorder Overview and Implications for School Counselors Ashley Eldridge, M.Ed.

Objectives of Session: History of the disorder as a DSM diagnosis Overview of perinatal neurobiology Current diagnostic criteria under the DSM-V Risk factors associated with RAD/DSED Characteristics of RAD/DSED Assessing children for RAD/DSED and monitoring progress Treatment Implications for school counseling and the classroom

Theories of Attachment Two basic theories, of which, one is the dominant Behavioral Theory Attachment is the result of conditioning as a result of the primary caregiver feeding her infant (Miller and Dollard, 1950) A baby associates his mother with food and, therefore, responds positively to her even after food is no longer a tangible reward This theory underestimates the impact on long term development of a primary caregiver s impact on the infant in-utero and in infancy

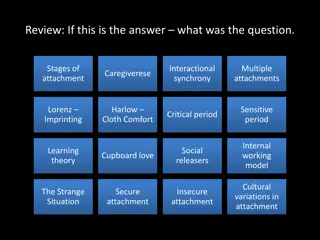

Theories of Attachment Evolutionary Theory Primarily attributes to John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth Based in the work of Lorenz (1935) and Harlow (1958) Creatures avoid pain and seek comfort from the earliest stages of development Universal need to seek proximity to our primary caregiver when there is a threat The caregiver provides safety, security, and for our physical needs This behavior, coupled with an attuned and affectionate caregiver and our genetics, lays the foundation for attachment to take place

Attachment Styles Secure Secure - infant is sad when mother leaves and happy when she returns Avoidant Avoidant - infant demonstrates neither distress nor excitement when the caregiver either leaves or returns Indicative of rejection of the infant s needs or affection Resistant Resistant - infant resists the caregiver leaving, but is fussy upon her return Indicative of an inconsistency in the child's needs being met Disorganized/Disoriented Disorganized/Disoriented - high levels of insecurity throughout the Strange Situation Task. Confusion when reunited with the mother. Indicative of abuse and/or neglect Associated with attachment disorders

Neurobiology of Attachment Individual gene expression and experience in-utero create a foundation or predisposition (risky or healthy) for attachment Experiences in infancy either build upon, repair, or destroy the foundation Maturation of the brain is experience dependent (Schore, 2001) The psychobiological systems responsible for the earliest development of attachment are located in the limbic system.

Limbic System - Components & Responsibilities The limbic system is responsible for emotions, memories, and survival instincts. It promotes attachment, adaptations to the environment, and organization of new learning. Contains: Amygdala (perceptions of emotions and memory storage) Hippocampus (storage of long term memory) Thalamus (relaying sensory and motor signals; regulation of sleep, consciousness, and alertness) Hypothalamus (links nervous and endocrine systems responsible for fight-flight- freeze response) Basal Ganglia (motivation, procedural learning, cognitions, and emotions) Cingulate Gyrus (processing emotions and behavior regulation)

Stress Response Stress in humans activates the two aspects of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) Sympathetic (Gas) Responsible for hypermetabolic state Increases heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, muscle tone and alertness Releases noradrenaline, adrenaline, and corticotropins Parasympathetic (Breaks) Responsible for hypoarousal Conserves energies for repair, restoring resources, and feigning death Internal opioids are released to reduce pain, calm the involuntary functions of the body, and inhibit mobility/cries for help Infants lack the ability to self-regulate these functions, and therefore, rely on their caregiver to regulate for them

Stress Response Regulation & Attachment In Healthy Care: In Healthy Care: The caregiver regulates these states for the child. Regulation allows for infant to return to psychobiological equilibrium. The mother s actions provide the scaffolding needed for the maturation of the control system in the infant s right brain.

Stress Response Regulation & Attachment In Pathogenic Care: In Pathogenic Care: Instead of repairing, she induces further arousal (hyper- in abuse and hypo- in neglect), and the infants remains in these intense neurobiological states. After the infant is allowed to persist in a state of fear, this state of hyper/hypoarousal becomes a trait. The infant s developing brain is exposed to neurotoxic levels of neurotransmitters such as glucocorticoids, responsible for selectively induced cell death in the limbic system. (Corbin, 543)

Neurological Results of Trauma Result in permanent changes in opiate, corticosteroid, CRH, dopamine, noradrenaline, and seratonin receptors. The result is permanent physiological reactivity in the limbic system. Young children with internalizing and externalizing problems show greater EEG activity in the right brain. MRI shows decreased hippocampus and amygdala size in adults who experienced early maltreatment (Corbin, 544) Smaller corpus collosum (responsible for communication between right and left hemispheres), which results in lateralization of the brain.

Pathogenic Care Persistent disregard for an infant s basic emotional and physical needs During Pregnancy: Substance use/abuse during pregnancy (remember the foundation!) High levels of stress In infancy: Maternal ambivalence or depression Frequent interruptions of care (failed adoptions or multiple foster placements) Neglect of emotional and primary physical needs Chronic Illness Emotional Abuse

History of RAD in the DSM 1980 - DSM III introduced Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) Categorized under the category of Disorders Usually First Diagnosed in Infancy, Childhood, or Adolescence DSM III-TR introduced two subtypes: Disinhibited (externalizing) Inhibited (internalizing) DSM IV and IV-TR - minimal to no changes

Changes in the DSM-V Attachment disorders are now classified as Trauma and Stress Related Disorders Instead of two subtypes, there are now two distinct disorders: Reactive Attachment Disorder (known as Inhibited Type in DSM-IV-TR)** Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder (formerly known as Disinhibited Type in DSM-IV-TR) Different comorbidities between the two subtypes Not viewed as a lack of attachment, rather an issue of unmodulated and indiscriminate attachment and social behavior

Criteria for Reactive Attachment Disorder in the DSM-V Pattern of extremes of insufficient care, attributed to at least one of the following: Social neglect or deprivation - persistent lack of meeting a child s emotional need for comfort, stimulation, and affection by care-giving adults Repeated change of primary caregiver, limiting opportunities to form stable attachments (i.e. frequent changes in foster care) Rearing in unusual setting that severely limits the opportunity to form selective attachments (i.e. high institutions with high caregiver to child ratio) Removed criteria of disregard for physical needs due to the emphasis on the fact that these are disorders of social relationships

Criteria in DSM-V for Reactive Attachment Disorder (cont d) Symptoms persist longer than 12 months and before age 5 Child s developmental age is at least 9 months Consistent pattern of inhibited, emotionally withdrawn behavior toward caregivers Persistent emotional and social disturbance Child does not meet the criteria for autism spectrum disorder **

DSM-V Characteristics Reactive Attachment Disorder Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) (RAD) Disinhibited Social Engagement Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder (DSED) Disorder (DSED) Failure to seek and respond to comfort when distressed Lacks wariness of strangers Unusually comfortable with strangers particularly adults Limited social reciprocity Limited emotional regulation Lacks appropriate physical and social boundaries Reduced positive affect Unexplained fearfulness or irritability

Characteristics of RAD Fails to initiate and respond to social interactions in a developmentally appropriate way Does not seek or offer comfort Withdraws from others, especially when a threat is perceived Shows frozen watchfulness or hypervigilance Demonstrates self-soothing behaviors Fails to seek help Demonstrates aggression towards peers (especially if they are the source of the perceived threat)

Basis of Aggressive Behavior Lack of empathy Negative self-school image (assumed inadequacy) Difficulty learning from mistakes Deficits in social information processing Misperceptions of other people s actions/intentions Stunted moral development Need for immediate gratification Inability to self-soothe or calm (Shaw & Paez, 2007)

Characteristics of DSED (Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder) Consistent childish behavior, inappropriate for developmental age Inappropriate affectionate or familiar behavior with relative strangers Seeks comfort from strangers Expresses distress for no apparent reason Chronically anxious Poor peer relationships

Characteristics Demonstrated in Both Attachment Disorders Aggression Victimization of other children or animals Poor impulse control Hyperactivity or inattention Low frustration tolerance Lack of empathy Self serving behaviors such as hoarding food, stealing, and lying

Assessment Some assessments currently used to diagnose and monitor characteristics of RAD/DSED are: Child Behavior Checklist Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC) Randolph Attachment Disorder Questionnaire (RADQ) (Becker-Weidman, 2006) Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment (CAFAS) (Becker-Weidman, 2006) Childhood Attachment & Relational Trauma Screen (CARTS) (Frewen et al., 2013) A diagnosis should only be made by a qualified mental-health professional with thorough understanding of the student and RAD after considering information from multiple sources.

Differential Diagnosis PDD-NOS Autism Spectrum Disorder Cognitive Impairment ADD/ADHD Depression Adjustment Disorders Anxiety Disorders

Treatment Goals for RAD 1.Security a.Psychological and physical safety b.Listen to the child without judgement c.Limits are set with empathy and compassion 2.Stability a.Permanence of an attachment figure b.Recognition of their own needs and trust that these needs can be consistently met c.Separations will often result in defensiveness and withdrawal 3.Sensitivity a.Emotional availability b.Understanding that the child is just beginning to develop the ability to appropriately experience and process emotions (Lubit et al, 2015)

Treatment Approaches Used with RAD Patients Trauma Therapy Dyadic Development Therapy Trauma Focused CBT Attachment Therapy Narrative Therapy Psychdrama Family Therapy EMDR Therapy (Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing)

Dyadic Developmental Theory Maintenance of a collaborative and affectively attuned relationship between therapist and child, child and caregiver, as well as the caregiver and therapist is essential. (Becker-Weid, 2006) Models healthy attachment Focuses on the caregiver s attachment style and attempts Emphasis on PLACE (playing, laughing, accepting, curious, emphasizing) Deep acceptance of child s experience and affect

Attachment Therapy Popularity is based in anecdotal accounts of success and limited research Popularity is based in anecdotal accounts of success and limited research in evidence in evidence- -based treatment based treatment (Wimmer, Vonk, and Bordnick, 2009) (Wimmer, Vonk, and Bordnick, 2009) Several techniques associated with AT are controversial. Several techniques associated with AT are controversial. Recommended: Narrative therapy Parenting Skills Training EMDR Neurofeedback Psychodrama Discouraged: Coercive Restraint Therapy (Mercer, 2005) Used to stress the caregiver or adult s authority Also called: Rage Reduction Re-birthing

School Counseling - So what? The main for chldren with attachment disorders is that the substrate of classroom life is social and emotional (Marcus & Sanders-Reio, 2001), both area of difficulty for children coping with effects of attachment disorder and complex trauma. (O Neill, Guenette, and Kitchenham, 2010) Students who cannot pay attention, follow directions, get along with others, or control negative emotions do relatively poorly in school. (Schwartz, 2006)

School Counseling - So What? Schools themselves pose a unique challenge to children diagnosed with RAD. While the mission of the school is to educate students, children with RAD are preoccupied with internal issues of safety, security, and trust. The need for survival, given their history, can be overwhelming, leaving them unable to profit from a learning environment. The child s need for survival and acute hypervigilance works against the organizational skills needed for school functioning. (Schwartz, 2006)

SO THEN, we must keep in mind that children need us to... Understand the behavior Use patience before punishing Listen, talk, and play with these Interact with the child based on children their emotional age Ensure the child s safety Be consistent predictable Stabilize immediate crises as routine they happen Model and teach appropriate Set realistic expectations social behaviors

Implications for School Counseling Educate colleagues who will work with students with RAD/DSED Administration for Manifest Determination Meetings Teachers, coaches, specialists, transportation, nutrition Collaborate with private practitioners Help families find community serve providers properly trained and equipped to support the needs of the child Inform therapists of patterns of behavior in school environment Assessment, Referral and Service Provision through IDEA or 504

Cautions and Considerations for School Counselors Don t refer families and children to practitioners with whom you are not familiar (Do no harm) Keep in mind that a suggestion or diagnosis of RAD or DSED is an explicit condemnation of parents, the foster care system, or both. This condemnation could be perceived as a personal attack or accusation of abuse. Work with the parents, not against them. (Shaw & Paez, 2007)

Cautions and Considerations for School Counselors Consider the complications that could be caused by information/beliefs parents/guardians of students with attachment disruptions may hold about traditional counseling versus therapies or methods to which they ve been introduced and told are effective with children like theirs . If you believe a child to be in psychological or physical danger, share your concerns and consider making a referral to DHR.

Implications for Teachers Provide stucture, routine, and consistency Remain neutral when addressing misbehavior Model and teach self-calming techniques and self-talk

Recommendations for Teachers DO DO Respond with action, not anger Establish and maintain clear boundaries Communicate directly with the child s parents Hold student accountable to their developmental level Create opportunities for restitution Maintain a professional, business-like attitude Provide an environment of safety, psychologically and physically DO NOT DO NOT Speak or act with anger towards any student Use repeated and second chances Allow 1-1 time alone with the student Attempt to play a motherly or nurturing role Send home behavior information with the student Scold, embarrass, or condemn a student Avoid emotional pressure when disciplining

Questions or Comments Ashley Eldridge, M.Ed. School Counselor at Brookwood Forest Elementary (205) 414-3700 eldridgel@mtnbrook.k12.al.us http://www.mtnbrook.k12.al.us/Page/2299

References: American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.) Washington, DC; Author. Becker-Weidman, A. (2006) Treatment for Children with Trauma-Attachment Disorders: Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal. Vol. 23: 147 Dollard, J. & Miller, N.E. (1950). Personality and psychotherapy. New York: McGraw-Hill Corbin, J.R. (2007). Reactive Attachment Disorder: A Biopsychosocial Disturbance of Attachment. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, Vol 24: 539 - 552. Frewen, P.A. et al. (2013) Development of a Childhood Attachment and Relational Trauma Screen (CARTS): a relational-socioecological framework for surveying attachment security and childhood trauma history. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. Vol. 9:4. Leveille, M. (2014). DSM-5 and School Psychology: Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder. Communique, Vol. 42, Issue 8. Lubit, R.H. et al. Attachment Disorders Treatment and Management. Retrieved from Medscape, Sept. 2016. from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/915447-treatment..

References Continued Mercer, J. (2005). Coercive Restraint Therapies: A Dangerous Alternative Mental Health Intervention. Medscape General Medicine, 7(3), 6. O Neill, L., Guennette, F., and Kitchenhamm, A. (2010) Am I Safe and Do You Life Me? Understanding complex trauma and attachment disruptions in the classroom. British Journal of Special Education. 37 (4): 190-193. Perry, B.D., (The ChildTrauma Academy). (2013) 3: Threat Response Patterns [Video webcast]. In Seven Slide Series. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sr-OXkk3i8E&feature=youtu.be Schore, A.N. (2001). Effects of Relational Trauma on Right Brain Development. Infant Mental Health Journal, Vol. 22, 201 - 269. Schwartz, E. and Davis, A. (2006). Reactive Attachment Disorder: Implications for School Readiness and School Functioning. Psychology in the Schools. Vol.43 (4): 471-479. Shaw, S.R. & Paez, D. (2007). Reactive Attachment Disorder: Recognition, Action, and Considerations for School Social Workers. Children & Schools 29 (2):69-74.