Understanding the Presumption of Innocence in European Criminal Law

Explore the intricate aspects of the presumption of innocence in European criminal law, including formal and informal limitations, comparative perspectives, and the relationship with other procedural mechanisms. Delve into the complexities of proving actus reus and mens rea, European jurisprudence on reverse burdens, and EU competence in criminal matters.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Formal presumption of innocence: A Comparative and European Perspective and informal or de facto limitations on the by Dr. Gerard Conway Brunel University of London

Abstract The presumption of innocence has now become established itself almost universally as a prerequisite of a fair criminal trial, but its scope and relationship with other procedural mechanisms remains blurred even in a European context where considerable progress has been made in establishing common norms of due process. In Europe, the presumption of innocence is recognised in Article 6(2) of the European Convention on Human Rights, Article 48 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, and in somewhat more detail in EU Directive 2016/343 on the strengthening of certain aspects of the presumption of innocence and the right to be present at trial. In many legal systems, the presumption of innocence interacts with other mechanisms of trial, rules of procedure and evidence, that can significantly affect its practical operation. In France, for example, it has sometimes been said that an informal presumption of guilt almost exists in the context of close relations between the prosecution and trial judges and the overwhelming numerical success of prosecutions in returning a guilty verdict; in other words, the principle in its effect may be impacted by the overall equality of arms between the parties to a criminal trial. The presumption is not without formal qualification, for example, concerning inferences from silence or non-cooperation; and it is not generally expressed in non-derogable terms. This paper considers the question of formal and informal or de facto restrictions on the presumption of innocence from a comparative point of view in order to assess a core of the concept beyond that currently recognised in EU Directive 2016/343 and that could inform recognition of the presumption in ECJ caselaw, for example, in the context of the European Arrest Warrant and the work of the European Public Prosecutor.

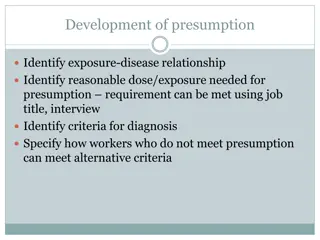

Aspects of the presumption of innocence Proving by prosecution of at least actus reus Mens rea? If part of the offence, similar logic seems to apply But how proof is demonstrated is a matter for national law, as things stand European jurisprudence on reverse burdens not excluded, but must have genuine possibility to rebut

EU competence Article 82 TFEU: 2. To the extent necessary to facilitate mutual recognition of judgments and judicial decisions and police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters having a cross-border dimension, the European Parliament and the Council may, by means of directives adopted in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure, establish minimum rules. Such rules shall take into account the differences between the legal traditions and systems of the Member States. They shall concern: (a) mutual admissibility of evidence between Member States; (b) the rights of individuals in criminal procedure; (c) the rights of victims of crime; (d) any other specific aspects of criminal procedure which the Council has identified in advance by a decision; for the adoption of such a decision, the Council shall act unanimously after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament. Adoption of the minimum rules referred to in this paragraph shall not prevent Member States from maintaining or introducing a higher level of protection for individuals.

Directive Art. 3 Presumption of innocence, for both suspects and accused Art. 4 Public references to guilt Art. 5 Presentation of suspects and accused persons Art. 6 Burden of proof + Recital 22: without prejudice to any ex officio fact-finding powers of the court, to the independence of the judiciary when assessing the guilt of the suspect or accused person, and to the use of presumptions of fact or law concerning the criminal liability of a suspect or accused person Art. 7 Right to remain silent and right not to incriminate oneself

Features of Directive Distinguishes (i) presumption of innocence (Art. 3) and (ii) burden on prosecutor (Art. 6(1)) (i) right to silence (Art. 7(1)) and (ii) right not to self-incriminate (Art. 7(2)) Application to suspects both suspects and accused equally within scope of wording of Art. 3 Possibly goes further than ECHR on negative inference from right to silence: ECHR Art. 7(5)

Commission Evaluation 2021 Careful and circumspect, does not single out MSs for non-compliance Notes biggest issue is as regards statement of guilt in absence of conviction, prohibited under Art. 4 How it measures non-compliance: Lack of exact legislative equivalent? Lack of caselaw reflecting similar principles? Lack of supporting practice? Notes one MS where burden of proof on judge (Germany?)

ECJ caselaw - Milev 42 that the Member States are to ensure that suspects and accused persons are presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law. As regards the other provisions of Directive 2016/343 mentioned by the referring court, it should be noted that Article 3 of that directive provides 43 a suspect or an accused person has not been proved guilty according to law, judicial decisions in particular, other than those on guilt, do not refer to that person as being guilty, without prejudice to preliminary decisions of a procedural nature which are taken by judicial authorities and which are based on suspicion or on incriminating evidence. In that connection, Article 4(1) of that directive provides that the Member States are to take the necessary measures to ensure that, for as long as 44 without prejudice to decisions on pre-trial detention, provided that such decisions do not refer to the suspect or accused person as being guilty. According to the same recital, before taking a preliminary decision of a procedural nature, the judicial authorities might first have to verify that there is sufficient incriminating evidence against the suspect or accused person to justify the decision concerned, and the decision could contain reference to that evidence. That provision must be read in the light of recital 16 of Directive 2016/343, whereby observance of the presumption of innocence should be 45 minimum rules concerning certain aspects of the presumption of innocence and the right to be present at the trial. Moreover, it should be noted that the purpose of Directive 2016/343 is, as is clear from Article 1 and recital 9 thereof, to lay down common 46 of procedural rights of suspects and accused persons, in order to strengthen the trust of Member States in each other s criminal justice systems and thus to facilitate mutual recognition of decisions in criminal matters. Furthermore, Directive 2016/343 confines itself, in accordance with recital 10 thereof, to establishing common minimum rules on the protection 47 and exhaustive instrument intended to lay down all the conditions for the adoption of decisions on pre-trial detention. Accordingly, in the light of the minimal degree of harmonisation pursued therein, Directive 2016/343 cannot be interpreted as being a complete 48 do not preclude the adoption of preliminary decisions of a procedural nature, such as a decision taken by a judicial authority that pre-trial detention should continue, which are based on suspicion or on incriminating evidence, provided that such decisions do not refer to the person in custody as being guilty. Moreover, in so far as, by its questions, the referring court seeks to ascertain the circumstances in which a decision on pre-trial detention may be adopted, and has doubts, in particular, as to the degree of certainty which it must have concerning the perpetrator of the offence, the rules governing examination of various forms of evidence, and the extent of the statement of reasons that it is required to provide in response to arguments made before it, such questions are not governed by that directive but rather fall solely within the remit of national law. It follows from the foregoing that, in the context of criminal proceedings, Directive 2016/343 and, in particular, Article 3 and Article 4(1) thereof,

ECJ caselaw Case C-644/23, Stangalov,16thJan. 2025 in absentia trials (etc most recent cases) Case C-175/22, BK with the participation of Spetsializirana prokuratura, 9thNov. 2023 - Art. 6(4) of Directive 2012/13/EU precludes national case-law allowing a court to use a legal classification of the acts at issue different from that initially used by the public prosecutor s office without informing the accused person of the new envisaged classification in due time, at a point and under conditions enabling him or her effectively to prepare a defence, and, accordingly, without offering that person the opportunity to exercise rights of defence specifically and effectively - Arts. 3 & 7 of Dir. 2016/343 do not preclude that charges can be substituted with new charges by court provided that court or tribunal has informed the accused person of the new envisaged classification in due time, at a point and under conditions which have enabled him or her effectively to prepare his or her defence, and has thus offered that person the opportunity to exercise his or her rights of defence specifically and effectively (Arts. 3 & 7) broader issue of linking presumption of innocence to defence rights/effectiveness more generally

Formal limitations (i) Reverse burden of proof: Rec. 22 of Dir. 2016/363: Such presumptions should be rebuttable and in any event, should be used only where the rights of the defence are respected. Widespread: Each defense yields a different constellation of jurisdictions concurring that the defendant bears the burden of persuasion on that particular defense. Fletcher (1965), 885 Limited reversal enough to raise a doubt, or prima facie , or evidential Typical reading defences, e.g. insanity

Formal limitations Ireland (reverse burden) CW v. Minister for Justice & Ors [2023] IESC 22, (Supreme Court, O Donnell C.J. & Charleton J., 28 August 2023) O Donnell C.J. found for the Supreme Court regarding s. 3(3) of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act 2006, which provides a defence to a charge of defilement of a child under 17 where it can be demonstrated that the accused reasonably believed the child was over this age. Stack J. in the High Court had held that the effect of the provision was that the accused was obliged to discharge a burden of proof, on the balance of probabilities, in respect of a core element of the offence, namely, the age of the child, and she considered that such a burden was not constitutionally permissible and breached the right to be presumed innocent. The Supreme Court upheld the High Court s conclusion, finding that s. 3(3) created a burden of proof on the balance of probabilities on an accused to show he or she genuinely believed the child not to be under 17 and created an unnecessarily high risk of conviction of a person who was so mistaken and thus violated the right to a fair trial in Art. 38.1 of the Constitution. Charleton J. concluded similarly, but held also that the burden of proof on an accused could not be more than to show a reasonable doubt.

Formal limitations (ii) Inferences from silence: Rec. 24 of Dir. 2016/363: The right to remain silent is an important aspect of the presumption of innocence and should serve as protection from self-incrimination. Art. 7(5) quite far-reaching: The exercise by suspects and accused persons of the right to remain silent or of the right not to incriminate oneself shall not be used against them and shall not be considered to be evidence that they have committed the criminal offence concerned. Ireland: Here, membership of a secret and criminal group is notoriously difficult of to prove , denial is a matter of choice for a suspect and inference from failure to respond is only possible where that logically arises and is capable only of being supporting evidence. Braney v Special Criminal Court & ors [2021] IESC 7 (12 February 2021), para. 67

Formal limitations (ii) Inferences from silence: Issue not explicitly addressed in Article 6 ECHR ECtHR: Saunders v UK, Sweeney v Ireland, Murray v. UK (1996) 22 EHRR 29, para. 47: a conviction should not be based solely or mainly on the silence of the accused but that silence can be taken into account in situations which clearly call for an explanation .

Informal limitations (i) Absence of specific evidence thresholds free evaluation of evidence Germany Section 261 of the Strafprozessordnung [StP0] (Code of Criminal Procedure), which provides that triers of fact should evaluate evidence freely, unrestrained by rules ranking competing kinds of evidence (Urie Beweswfirdigung) (ii) Opinion evidence Ireland See above (iii) Prejudicial publicity Ireland D v. DPP [1994] 2 I.R. 465, 474. Denham J. (as she then was) recognised that there is a hierarchy of rights in criminal proceedings, with the right to a fair trial at the apex, but it was up to the accused to establish that there is a real risk that by reason of those circumstances he could not obtain a fair trial perceived as difficult to meet this test

Limitations & the Directive Dir. 2016/343 addresses formal limitations The informal limitations listed above are not addressed Addressing them arguably is within the concept of minimum rules in Art. 82 TFEU

France Section 9 of the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man, which begins: Tout homme tant presum innocent jusqu'a ce qu'il ait t d clar coupable. Everyone being presumed innocent until proven guilty Incorporated by Preamble to Constitution of Fifth Republic Art. 310 CPP on duty of judge to ascertain facts beyond submissions of parties

Sweden Not expressly in RB, but right to fair trial in Chap. 2, Art./Sec. 11 of the Instrument of Government 1974: Art. 11. No court of law may be established on account of an act already committed, or for a particular dispute or otherwise for a particular case. Legal proceedings shall be carried out fairly and within a reasonable period of time. Proceedings in courts of law shall be open to the public. C. Wong, Overview of Swedish Criminal Procedure (University of Lund 2012)

Sweden MA & AS Case no. B 2354-22 delivered in Stockholm on 14 February 2023: 17. The substantial evidentiary requirement for a person to be convicted of an offence is based on the presumption of innocence, which is part of the provisions on a fair trial in Chapter 2, Section 11, second paragraph of the Instrument of Government and Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The evidentiary requirement is essential to prevent innocent people from being convicted. The requirement also aims to avoid that convictions that have become legally binding are later overturned due to new facts or evidence. 18. Difficulties encountered by the prosecutor in obtaining evidence do not normally entail a less demanding evidentiary requirement. In case law, however, a reduced and differently worded requirement has been accepted in certain specific circumstances, in particular the defendant's objections to discharge from liability on the grounds of self-defence or similar circumstances, in which case it is considered sufficient for the prosecution to present enough evidence to make the objection appear unfounded. The main reason for the reduction of the burden of proof is that in these situations the prosecutor must prove that something did not happen. (See, e.g., "M ls gandens lder" para. 18)

Sweden Code of Judicial Procedure on prosecutor: Chap. 45, art./sec. 4: In the application for a summons the prosecutor shall identify: the defendant; the aggrieved person if there is any; 3. the criminal act, specifying the time and place of its commission and the other circumstances required for its identification, and the applicable statutory Section or Sections; 4. the means of evidence he wants to invoke and what he intends to prove by each specified means; and 5. the circumstances giving the court competence, unless this is apparent from what is otherwise stated. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Presumption of innocence versus burden on prosecutor? Statements as to guilt unappealable if obiter? Sww Wong (2012), sec. 5.1

General points Need to formulate express presumption? Could Commission enforce against Sweden for absence, e.g. compare articles of Dir. with Swedish law Should Commission leave level of formulation to national law? e.g. Constitution, jurisprudence, statute, cf. 2021 Evaluation Report How far should the EU exercise a competence? Can a uniform role going beyond what most or all of MSs currently legislate for fall within concept of minimum rule , is latter a more general term to indicate reserve of overall competence to MSs?

Other references Mario Caterini, The Presumption of Innocence in Europe: Developments in Substantive Criminal Law , 8 Beijing LR 100-140 (2017) Stephanie de Bruyn, A comparative legal analysis on pretrial publicity prejudice in jury trials: who is the fairest of them all? , Jg. 60 nummer 2 Jura Falconis 4-80 (2023 2024) Zelam Cowen, Prejudicial Publicity and the Fair Trial: A Comparative Examination of American, English and Commonwealth Law, Addison C. Harris Memorial Lecture," 41(1) Indiana Law Journal 69-85 (1965) George P. Fletcher, Two Kinds of Legal Rules: A Comparative Study of Burden-of Two Kinds of Legal Rules: A Comparative Study of Burden-of Persuasion Practices in Criminal Cases Persuasion Practices in Criminal Cases , 77 Yale LJ 880-935 (1968) Peo Mesepole, Should Ireland Prohibit the Contemporaneous Media Reporting of Juvenile Trials , 5(1) Irish Judicial Studies Journal 71-99 (2021)