Women's Status in Myanmar's Historical Context

Explore the evolving status of women in Myanmar through the lens of early history, including the Pyu and Mon Kingdoms, as well as the Bagan Kingdom and the colonial period. Discover how women's roles, rights, and influence shifted over time in Myanmar's rich cultural heritage.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

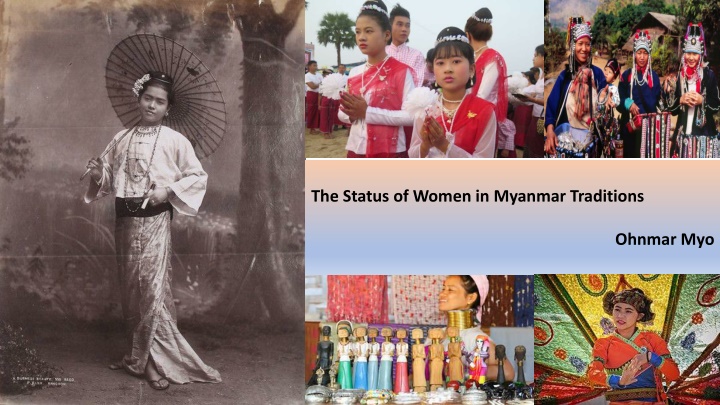

The Status of Women in Myanmar Traditions Ohnmar Myo

Status of Women in Early History (Pyu and Mon Kingdom) The earliest historical record of the status of women of Pyu Kingdom of Srikestra could be found in the Chinese sources of Tan History in the 9th Century AD. When they come to the age of seven, both boys and girls drop their hair and stop in a monastery where they take refuge in the Sangha. On reaching the age of twenty, if they have not awakened to the principles of the Buddha, they let their hair grow again and become ordinary townsfolk. ( G. H. Luce, The Ancient Pyu: JBRS, vol XXVII) It shows that Pyu boys and girls had equally been treated to take refuge, which is one of the greatest privileges given to human- beings in Buddhism. In the Mon kingdom, a woman s merit-making has been noticed by the discovery of the votive tablets found in the Kawkun cave in present Hpa-An in the Karen state. This image of Buddha, it was, I, queen of Mataban dwelling in the town of Duwop who carved it and made this holy Buddha. The votive tablets of earth in Duwop and elsewhere in this kingdom, it was I and my followers alone who carved them. (Nai Pan Hla, Mon Literature and Culture over Thailand and Burma: (JBRS, vol XLI) From this evidence, the Mon Kingdom had a Queen since the early period of when the votive tablets of Buddha were made to let others could gain merit by their devotions.

Status of Women in History (Bagan Kingdom) In the great Bagan era, thousands of monuments were built over centuries, the inscriptions were erected, with the names of donors who also gave temples, monasteries, lands and labourers and these include women as well as men. The inscriptions are meant to show piety but their relevance is their indication of the status of women at that time. The women had obviously rights not only to own property but also to dispose of it as they wished. The inscriptions showed the rights of women in law cases. They could sue and could defend themselves if sued. Professor G.H.Luce said, women could earn, own and inherit property in their own right apart from their husbands. Most of the law suits recorded are about the ownership of slaves and involve women suing each other. Slaves here mean the people who served to the pagodas and or monasteries to offerings and festivals. Dr Than Tun mentioned that women donors like men, often showed concern for the welfare of such pagodas subjects. Some reserved the land for their use, a woman gave detailed instructions to ensure their food, another stipulated that when her pagoda subjects got old or ill, the monks must give them proper treatment. Dr Pe Maung Tin mentioned that women are also shown in administrative positions. Women headpersons of villages, women chiefs and assistant chiefs of the community projects and some were officials at the court in Bagan period. Princess Thanbyin, daughter of King Kyawswa could debate with the monks, left a treatise on Pali case called Vibhattyattha.

Status of Women at Colonial Period Harold Fielding Hall, a late nineteenth-century British officer in Burma writing at the turn of the century, claims that a Burmese woman, unlike a European or an Indian woman, has been bound by no ties (Hall 1898:173). He elaborates: You see, she [a Burmese woman] has had to fight her own way; for the same laws that made woman lower than man in Europe compensated her to a certain extent by protection and guidance. In Burma she has been neither confined nor guided. In Europe and India for very long the idea was to make woman a hot-house plant, to see that no rough winds struck her, that no injuries overtook her. In Burma she has had to look out for herself: she has had freedom to come to grief as well as to come to strength. National Character, in which James Scott attempts to outline a Burmese national identity by comparing and contrasting women in Japan and in Burma: Both are frank, and unaffected, and have a charming artlessness, but the Burmese woman is far ahead of her lord in the matter of business capacity by the way in which she rules the household without outwardly seeming to exercise any authority. The Japanese wife treats her husband as an idol, the Burmese as a comrade. (1906:77)

Status of Women at Colonial Period The equally important and often overlooked premise for the comparison pertained to Eurocentric and Judeo-Christian notions of enfranchisement and citizenship based in turn on property rights. Studies of legal texts by British officials and scholars and their ideas of Burmese Buddhist or customary law placed emphasis on the division of marriage property in divorce and the equal rights of women to inherit. Hall asserts that women in Burma have always had freedom from sacerdotal dogma, from secular law (1898:172) and in no material points, hardly even in minor points, does the law discriminate against women (171). Writing a decade after Hall, another British officer, R. Grant Brown, similarly stresses the gender equality underlying norms and practices pertaining to marriage, inheritance, and ownership in Burma: [N]ot only do sons and daughters inherit equally from their parents, but a married woman has an absolute right to dispose as she pleases of property. The chapter titled Law and Justice Under Burmese Rule, in John Nisbet (1901:176 189).Journal of Burma Studies, Volume 10 59 The Traditional High Status of Women in Burma acquired or inherited by her either before or after marriage. She is usually a partner in her husband s business, and as such as just as much right to sign for the firm as he; but she may have a business of her own, with the proceeds of which he cannot interfere. Even in matters in which she has no part, she is usually consulted before an important step is taken. . . . (1911:217)

Status of Women at Colonial Period That women in Burma had categorically gained a reputation for their liberty can also be discerned from an article written for Times India by Sir Harcourt Butler, who served as Governor of Burma from 1923 until 1927, in which he points out that what distinguishes Burma from India and makes Burma one of the fairest countries of the British Empire is that the Burmese women do not wear purdah (Butler 1930). The reputation of traditionally liberated Burmese women at least as such outsiders as colonial travelers and officials understood it was inextricably intertwined with their comparative perception of predominantly Buddhist women in Burma to Hindu, Muslim, and Christian women in Britain and in British India. The comparison was founded upon Orientalist representations of such traditional practices as sati and purdah in Hindu and Muslim societies, and the lack thereof in Buddhist societies.

Views of Myamar Scholars Altogether, in our social life as well as in our public life, we feel that we, as Burmese women, occupy a privileged and independent position. It is a position for which we are trained almost imperceptibly, and with love and security from childhood. It is a position which is not limited either by marriage or by motherhood, and which allows us, eventually, to fit ourselves into the life, the work, and all the rewards that our country has to offer equally with our men. (Daw Mya Sein (1904-1988), Writer, Educator and Historian) The traditional autonomy of Burmese women was constructed in opposition to the likewise traditional subordinate status of women in South Asia and in contestation of the superiority of European culture and society. (Dr Chie Ikeya, Associate Professor of History, Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences

A 1914 survey of thirty intervieweesconsisting of Burmese and English university professors, Christian missionaries, and government officials conducted by the Christian Literature Society, which summarizes the interviewees opinions regarding the position of women in Burma: The women of Burma are said to enjoy already many of the privileges for which their Western sisters are clamoring. . . . It is probably true to say that whilst the position assigned to women in Buddhism is low, yet in practice the women of Burma have made a place for themselves which is certainly unique in the East; and in some ways in advance of that in the West if not actually, at least relatively, to the position of men. (Saunder 1914:63) According to the interviewees, women in Burma were more privileged and more advanced than women in other parts of the world, including the West.

In Buddhism, Buddha allowed women into a Bikkhuni, which gave to a woman the right to choose to leave the duties of the household in order to attend to her spiritual growth as an individual, just as a man is entitled to do. During the days of the Burmese kings, women were frequently appointed to high office and became leaders of a village, chieftainess, and even ruled as queen. And in a series of Burmese folk tales concerning wise and remarkable decisions in law, which have been collected by Dr. Htin Aung, the judge in each of the stories is a woman called "Princess Learned-in-the-Law." All these fields of administration, government service, law, medicine or business are always open to any Burmese woman who wishes to enter them.

Marriage A Myanmar girl does not change her name when she marries, nor does she wear any sign of marriage, such as a ring. Her name is always the same, and there is nothing to a stranger to denote whether she be married or not, of whose wife she is; and she keeps her property as her own. Marriage does not confer upon her husband any power over his wife s property, either what she brings with her, what she earns, or what she inherits subsequently; it all remains her own, as does his remain his own. It has often been said that the women do most of the hard work of the country. But this is not because they are the slaves of their husbands, as among savage warlike races. On the contrary, they occupy a position of independence and responsibility, and it is precisely this sense of responsibility, added to maternal love for their offspring, that makes them work hard when the husband fails to do his share.

The "arranged marriage," customary in so large a part of Asia, is still to be found in some segments of our society, but with this essential distinction: that the parents cannot choose a partner for their daughter without offering her the right of refusal. Most of our young people now marry for love or at least choose their own partners and a girl can insist that her parents accept her betrothal to the man she prefers. Even after her marriage a girl can decide, if she wants, to remain in her own family for a while. The marriage itself continues this principle of independence and equality. The wedding is not a religious ceremony but a civil contract in fact no ceremony is necessary at all; a man and woman can simply make known their decision to "eat and live together. If, by any chance, either partner of a marriage should wish to terminate their contract in divorce, this, too, is possible and acceptable under Burmese law. If there is mutual consent to the divorce, if the husband and wife both decide for whatever reason that they cannot live together, they simply announce the end of the marriage to the headman of the village or to the heads of the two families. But even without this amicable arrangement, a woman can divorce her husband for cruelty, serious misconduct, or desertion, regardless of his consent.

Legal Protection for Women During the British Colonial regime, the position of a non-Buddhist husband and Myanmar Buddhist wife was very unfavorable. While there is no provision in the Dhammathats that a Buddhist woman cannot marry another religious man, in this period, the Buddhist woman who married a non-Buddhist man almost lost her rights to divorce, inheritance, succession and their child's legal status. Almost all matters of divorce, inheritance, succession, partition and guardianship of children were decided by a foreign judge. To protect Buddhist women who married non-Buddhist men, the Legislative Council passed that relating Act in 1939 Myanmar Law Act No.24 of 1939). The Act came into force on 1 April 1941, but it was ineffective because of the 2nd World war. After independence, The Parliament of union padded the Myanmar Buddhist Women's Special Marriage and Succession Act, 1954(Myanmar Act No.32 of 1954) which repealed the former 139 Act. However, when the Myanmar Buddhist Women's Special Marriage and Succession Act, 1954 was passed, Myanmar Buddhist women who were married to non-Buddhist men did not receive relief from it because it had a lot of weaknesses. In order to provide effective legal protection to Myanmar Buddhist Women, Pyidaungsu Hluttaw passed Myanmar Buddhist Women Special Marriage Law, 2015 (PyiDaungSu Hluttaw Law No.50 of 2015) in 2015. The Monogamy Law states that it applies to everyone living in Myanmar, including foreign nationals married to Myanmar citizens. It prohibits a married person from entering a second marriage or unofficially living with another person while still married.

The Views of Myanmar Women Myanmar women like to give precedence to their men in their own homes because they acknowledge them, until their death, as head of the household. Possibly women can afford to offer them this courtesy because women are secure in their rights and status. We believe that when a new Buddha comes to the world it will be as a man (though, to be sure, one of us who is now a woman may, in a later life, be born as a man and eventually progress to Buddhahood). We feel that this gives men an inherent superiority: mentally, they can reach higher than women.

Status of Women in Current Period According to UN Women, Myanmar has achieved gender parity in education with regards to enrollment ratios of girls and boys in primary and secondary education. In the case of divorce, women in Myanmar enjoy equal rights regarding inheritance laws and equal marital property rights. The country has expressed its dedication to women s rights through the adoption of The Convention to Eliminate all forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in 1997. In 2013, the government approved a National Strategic Plan for the Advancement of Women, which identified twelve areas in which it must act for gender equality. Areas include poverty reduction, education, health care, inclusion in decision making and the promotion of the welfare of girls.

Gender Roles The gender roles arising from Myanmar culture provide women for enjoying their rights to personal safety, education, employment, freedom of movement, and participation in leadership, recreation and community activities. In the occupation, it is found that the occupations assigned to females are lower than that of males and most of the occupations that refer to females have low status compared to the men. However they, of course, have to take more activities as men. Women are major roles in doing social roles and religion. Chit ( 2006) states that Myanmar women are independent and are not subject to control. They feel satisfied in doing like that they give more favour to their husband and their son. Most of the women are raised to think that their greatest wish is to become dutiful wives of their husbands and that they have the duty to do the housework and to look after their children. As women are the protector of tradition, in Myanmar, the women are expected to take more responsibilities in doing in family affair and social affair except making the important decision in some cases. In Myanmar culture, it is accepted that men have to go outside for family income and women have to be in doors to take the responsibilities of the house. The results show that women are subordinate and inferior comparing with men although there is law that men and women can enjoy equal right. It is found that women have to carry out the primary position in doing many activities although they are always placed in the second position. It is obvious that women are in breast with the men although there is discrimination in some cases because of Myanmar tradition and culture. .

Gender Roles Gender issue is prominent in different countries in the world; however, little has been done to investigate gender roles and representations in Myanmar, a Southeast Asian country. According to Myanmar custom and tradition, women, rather than men, are expected to take care of their families (Department for International Development [DFID] Myanmar operational plan 2011 -gender annex, 2011). Yet at the same time, women have the right to do as they wish in the economy of their families. Although they do not take part in all family affairs, they can act as advisors to their husbands, or people to be consulted before important decisions are made (Minn, 2014). In education, girls and boys have equal right to enroll in the schools. In general, women have higher education and higher degrees than men. Although the number of educated women is higher than that of educated men, women have less chance to join in the labour force (Interim country partnership strategy, Myanmar, 2012-2014). In Buddhism, Buddha allowed women into a Bikkhuni, which gave to a woman the right to choose to leave the duties of the household in order to attend to her spiritual growth as an individual, just as a man is entitled to do. However, nuns and women have no right to offer gold leaves to the pagoda; instead, they have to ask men to do so. Women are forbidden by Myanmar tradition and culture to participate in some ceremonies and to enter some parts of a temple and a monastery (Belak, 2002). Therefore, women are given more rights in some cases and they are inferior in some cases.

Conclusion Myanmar women and girls are socially obligated and expected to be in charge of the household, children, elderly relatives, and take on other caring responsibilities. The expectation that males are leaders, combined with the social expectation that women play supportive roles, is entrenched in daily Myanmar life. Myanmar's Constitution (Section 347) includes the guarantee of equal rights and equal legal protection to all persons and (Section 348) does not discriminate against any Myanmar citizen on the basis of sex. Myanmar's legal framework, traditions, and religious beliefs protect women's rights. However, many concepts of the traditional role of women continue to keep women in Myanmar from gaining advancement. Traditionally, a woman in Myanmar is responsible for her family's well-being, while the husband earns the income for the household. Women continue to remain underrepresented in government positions, and women living in rural areas of the country face fewer opportunities for advancement than women in more urban areas of the country. Additionally, women belonging to ethnic minority groups face added discrimination and barriers to access, particularly those who are non Buddhists. Governmental strides towards women's equality have been made, particularly in establishing institutional agencies to address women's representation. Additionally, there have been changes centering general women's rights and women's representation. Despite this, there are still large cultural barriers, as well as additional disparities in access for women who are rural or ethnic minorities.