Chapter 5: Catalysis Explained

In Chapter 5, the concept of catalysis is delved into, covering homogeneous and heterogeneous reactions, types of catalysis, characteristics of catalytic reactions, mechanisms, and industrial applications. The role of catalysts in enhancing reaction rates under varying conditions is explored, along with the distinction between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalytic reactions.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

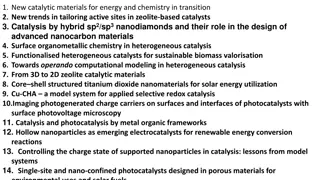

Chapter 5 Catalysis Contents 5.1 5.2 Homogenous and Heterogeneous 5.3 Types of Catalysis 5.4 Characteristics of Catalytic Reactions 5.5 Mechanism of Catalysis i. Intermediate compound formation theory. ii. Adsorption theory. 5.6 Industrial Applications of Catalysis Introduction Classification of Catalytic Reaction

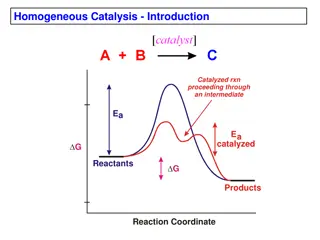

Fig. 5.1: Effect of varying conditions on rate of reaction Conclusion: By using high temperature or concentrated acid or powdered limestone. II. By using medium temperature or dilute acid or small lumps of limestone. III. By using very low temperature or very dilute acid or larger lumps of limestone. Rate of reaction increases with increase in concentration, temperature and decrease in particle size. It is found by experiments that some reactions speed up drastically by the presence of a specific chemical which itself remains unconsumed or unchanged at the end of reaction. Such Catalysts are the substances, which by their mere presence would bring about chemical reactions that would not take place if they were absent.

5.2 and Heterogeneous: 1. Homogeneous Catalytic Reactions (Homogeneous Catalysis): The catalytic reaction in which the reactants, products and catalyst are present in the same phase and the reacting system as such is homogeneous throughout is known as homogeneous catalysis. The kinds of phases by which homogeneous catalysis can be brought about are two viz. gaseous phase and solution phase. Accordingly, we have, (a) Gaseous phase catalysis: In this type of catalysis, the reactants and the catalyst are in gaseous phase. For example: (i) Manufacture of sulphuric acid by lead chamber process: 2SO2(g) + O2(g) 2SO3(g) Here the reactants sulphur dioxide, steam and atmospheric oxygen and the catalyst nitric oxide are all in the gaseous state. (ii) Oxidation of carbon monoxide: CO(gas) + O2(gas) 2CO2(gas) Here carbon monoxide and oxygen are in a gaseous phases and the catalyst nitric oxide is also in the same phase. Classification of Catalytic Reaction - Homogenous

(b) Liquid phase catalysis: In this type of catalysis, the reactants and the catalyst are in liquid or solution phase. For example: Inversion of cane sugar into glucose and fructose: C12H22O11(liq) + H2O(liq) C6H12O6(liq) + C12H22O11 Cane sugar Water Catalyst Glucose Fructose Here the catalysts as well as the reactants i.e. aqueous solution of mineral acid and cane sugar are both in the liquid phase. (ii) Enzyme catalysis: Hydrolysis of urea by Urease H2N CO NH2 + H2O 2NH3 + CO2 (Urea solution) (iii) Esterification: C2H5OH(liq) + CH3COOH(liq) CH3COOC2H5 + H2O Here all the components are in the same phase.

2. Heterogeneous Catalytic Reactions (Heterogeneous Catalysis): The catalytic reactions in which the reactants and the catalyst are in different phases constitute the heterogeneous catalysis. The system is homogeneous as for as the reactants are concerned but it becomes heterogeneous by the introduction of the catalyst in a phase different than that of the reactants. The various kinds of phase systems usually met with are solid-gas, solid- liquid, liquid-gas, and liquid-liquid (immiscible). In practice, the phase of catalyst is in solid state are called contact catalysis and are the most common. The solid catalysts generally used in this system are metals such as Pt, Ni, Cu, Fe, etc, mostly in the form of fine powder. Some metal oxides such as ZnO, Cr2O3, Bi2O3, MoO3, Al2O3, are also suitable for this purpose. (They serve as catalyst because of a variable co-ordination number, their oxidation state can be effectively increased by one or two units or intermolecular rearrangement occurs during reaction by insertion of one ligand between the metal atom and another ligand.)

Examples: (a) Manufacture of sulphuric acid by contact process: Pt(s((,\s\do8(V2O5(s 2SO3(gas) oxidizes sulphur dioxide gas to sulphur trioxide by oxygen. (b) Manufacture of ammonia by Haber process: N2(gas) + 3H2(gas) 2NH3(gas) It is an example of solid-gas system. Gaseous mixture of nitrogen and hydrogen is converted to gaseous ammonia by contact catalysis in presence of solid ferric oxide. (c) Hydrogenation of vegetable oils: X CH = CH Y(liq) + H2(gas) X CH2 CH2 Y Vegetable oils (l) Vegetable ghee (s) This is solid-liquid system where finely divided solid nickel acts as a catalyst which converts liquid reactant (oil) to solid ghee by reaction with hydrogen gas. (d) Conversion of acetic acid to acetone: CH3COOH + CH3COOH + (Al2O3) CH3COCH3 + H2O + (Liquid) (Liquid) (Solid) CO2 + (Al2O3) (Solid) This is solid-liquid system. (e) Hydrogen from water gas: (H2 + CO) + H2O CO2 + H2 (Water gas) (Steam) This is a solid-gas system where carbon monoxide from water gas gets oxidised to carbon dioxide by the action of steam in the presence of solid catalyst ferric oxide. Both types of catalysis discussed above are fundamentally similar. Of the two, heterogeneous catalysis has much greater economic impact from industrial point of view. 2SO2(gas) + O2(gas) This is an example of solid-gas system. Here v2o5 or platinized asbestos in solid phase, acts as a catalyst which

Examples: (a)Manufacture of sulphuric acid by contact process: 2SO2(gas) + O2(gas)Pt(s((,\s\do8(V2O5(s 2SO3(gas) This is an example of solid-gas system. Here v2o5 or platinized asbestos in solid phase, acts as a catalyst which oxidizes sulphur dioxide gas to sulphur trioxide by oxygen. (b)Manufacture of ammonia by Haber process: N2(gas) + 3H2(gas) 2NH3(gas) It is an example of solid-gas system. Gaseous mixture of nitrogen and hydrogen is converted to gaseous ammonia by contact catalysis in presence of solid ferric oxide. (c) Hydrogenation of vegetable oils: X CH = CH Y(liq) + H2(gas)X CH2 CH2 Y Vegetable oils (l) Vegetable ghee (s) This is solid-liquid system where finely divided solid nickel acts as a catalyst which converts liquid reactant (oil) to solid ghee by reaction with hydrogen gas.

(d) Conversion of acetic acid to acetone: CH3COOH + CH3COOH + (Al2O3) CH3COCH3 + H2O + (Liquid) (Liquid) (Solid) CO2 + (Al2O3) (Solid) (e) Hydrogen from water gas: (H2 + CO) + H2O CO2 + H2 (Water gas) (Steam) This is a solid-gas system where carbon monoxide from water gas gets oxidised to carbon dioxide by the action of steam in the presence of solid catalyst ferric oxide. 5.3 Types of Catalysis: 1.Positive catalysis, 2. Negative catalysis, 3. Auto-catalysis, 4. Induced catalysis, 5. Acid-Base catalysis and 6. Enzyme catalysis. This is solid-liquid system.

1. Positive catalysis: A catalyst which increases (enhances) the rate of the chemical reaction is called a positive catalyst and the phenomenon is called as positive catalysis. The majority of the reactions belong to this category. Examples: (a) Decomposition of KClO3 to prepare oxygen by using MnO2 is an example of positive catalysis. (b) Formation of HCl by using moisture H2 + Cl2 2HCl (c) Haber s process for manufacture of NH3 N2(gas) + 3H2(gas) 2NH3(gas) (d) Contact process for manufacture of H2SO4 2SO2 + O2 2SO3 2. Negative catalysis: A substance when added in a small quantity to the reaction mixture retards or inhibits the speed of reaction is called an anti-catalyst or negative catalyst or an inhibitor and the phenomenon is termed as negative catalysis. Negative catalysts are used to slow down or stop the reactions. They block one or more elementary steps in the catalytic reactions. These are better called catalyst poisons. Examples: (a) Use of sulphuric acid or glycerine retards the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide. (b) TEL tetra ethyl lead, is added to petrol as anti-knocking agent to retard its early ignition in an internal combustion engine and thus it minimizes the knocking effect. (c) The presence of small amount of alcohol retards the oxidation of chloroform to poisonous phosgene. 2KClO3 2KCl +3O2 H2O2Glycerine((((,\s\do8((Very slow H2O + O2

3. Auto-catalysis (self- catalysis): It is a catalytic reaction in which one of the products formed during the course of a reaction itself acts as a catalyst for the same reaction. Such a reaction is known as auto-catalysis or self-catalysis and the particular substance is called auto-catalyst or self-catalyst. Examples: (a) Permanganate method: In oxidation of oxalic acid by acidified KMnO4, the Mn2+ ions formed during the reaction act as the auto-catalyst and thereby speed up the reaction. Step I: 2KMnO4 + 3H2SO4 K2SO4 +2MnSO4 + 3H2O +5[O] (Auto cata.) Step II: 5[O] + 5H2C2O4 5H2O + 10CO2 Fast) Induced catalysis: A reaction which induces another reaction to proceed rapidly is called induced catalytic reaction. Examples: (i) Oxidation of Na3AsO3 in presence of Na2SO3: If sodium sulphite (Na2SO3) and sodium arsenite (Na3AsO3) are oxidised in air separately, only Na2SO3 is oxidised to Na2SO4, while Na3AsO3 does not change at all. Now if both are mixed together and subjected to atmospheric oxidation, Na2SO3 changes to Na2SO4 and Na3AsO3 to Na3AsO4. In this process, the presence of Na2SO3 causes the oxidation of Na3AsO3 to Na3AsO4. It is to say that the presence of Na2SO3, has induced the oxidation of Na3AsO3, hence Na2SO3 is called induced catalyst and the process is called induced catalysis. Na2SO3 + Na3AsO3 +O2 Na2SO4 + Na3AsO4 (Catalyst)

5. Acid-Base catalysis: The catalytic reactions caused by an acid are called acid-catalysis and those which are speeded up by the base as base-catalysis. Examples: (a) Inversion of cane sugar by dilute mineral acid: C12H22O11 + H2O C6H12O6 + C6H12O6 Cane sugar Water Glucose Fructose (b) The hydrolysis of nitrile to amide and then to ammonium salt: This is another example of acid-base catalysis. RCN + H2O RCONH2 RCONH2 + H2O RCOONH4 (Amide) Further, we may have electrophilic catalysis, nucleophilic catalysis, neutral salt catalysis, etc. depending upon the nature of the catalyst. 6. Enzyme catalysis: The number of chemical reactions occurring within plants and animals are catalyzed by certain enzymes (the complex organic molecules produced by living plants and animals) are grouped under enzyme catalysis. Examples: H2N CO NH2 + H2O 2NH3 + CO2 (Urea) (Ammonia) (Carbon dioxide) C6H12O6 2C2H5OH + 2CO2 (Glucose) (Ethyl alcohol) (Carbon dioxide) C12H22O11 + H2O 2C6H12O6 (Maltose) (Glucose) Nitrile

2. Common Salt (NaCl): This is required for salting out process during the manufacture of soaps. It should be free from impurities like Fe, Cu, and Mg. 3. Fats, Oils and Fatty Acids: a) Tallow: This is the principal fatty material used in the soap making. It is derived from the fat of cow, oxen, sheep, goat and other animals. It consists essentially of two glycerides: olein (40%) and stearin (60%). This is usually mixed with coconut oil to reduce the hardness and increase the solubility of the soap. b) Grease or lard: This is the second important raw material for soap making. It is obtained from pigs. It is a soft fat like butter and consists mainly of olein (60%) and stearin (40%). It is used in making best grade of soaps.

5.4 Characteristics of Catalytic Reactions: Criteria of Catalysis: Following are the various characteristics of a catalytic reaction or of a catalyst: 1. A small quantity of the catalyst: Usually a small amount of a catalyst is sufficient in many reactions to speed up reactions of huge amount of reactants. This is due to the fact that the catalyst is not used up in the reaction. Examples: (a) One milligram of platinum powder is sufficient to cause the union of 2.5 dm3 (liters) of a mixture of H2 and O2 to form water. (b) A trace of moisture is sufficient to bring about violent reaction between H2 and Cl2 to form HCl. Similarly, a trace of copper sulphate (say 10 12 g mole per dm3) is sufficient to accelerate markedly the oxidation of sodium sulplhite by air. Exception: In homogeneous catalysis where the catalyst forms an intermediate compound with the reactants, obviously a large quantity of catalyst is required. Example: In Friedel and Craft s reaction, the catalyst combines first with the halide to form an intermediate compound where the two substances must be present in molecular proportion. C6H5COCl + AlCl3 C6H5COCl AlCl3 Benzoyl chloride Catalyst Intermediate compound 2. Unchangeability of the catalyst: The catalyst remains unchanged at the end of the reaction i.e. the chemical composition and quantity of the catalyst remains the same but it may change in its physical form. Example: Manganese dioxide which is used as a catalyst to accelerate the decomposition of potassium chlorate, changes from crystalline/coarse to form a fine powder. In many other cases, shining surface of the catalyst becomes dull after use.

3. Catalyst can start a reaction: It was previous understanding that catalyst can never start a reaction. But this view has been disproved. There are a number of chemical reactions which are initiated by the catalyst. Baker has shown that in large number of reactions, if reactants are dry, reaction does not occur but if slight moisture is present, the reaction starts. Examples: Reaction between H2 and Cl2 is not possible in dry atmosphere. But as soon as slight moisture is added, spontaneous reaction occurs to produce HCl. Similarly, reaction between NO and O2 to produce NO2 starts only in the presence of moisture. 4. Specificity of catalysts: The phenomenon of catalysis is universal and specific. For every reaction, there is the most effective specific catalyst, but it is to be discovered by trial and experiments. There is no universal catalyst for all reactions. A particular catalyst can catalyze a particular reaction only. In other words, the action of catalyst is highly specific, i.e. a substance which acts as a catalyst for one reaction may fail to catalyze another. [Analogy: A particular key can open a particular lock. All the keys cannot open all the locks.] Examples: (a) Decomposition of formic acid. Metallic copper catalyses acid decomposition, to produce CO2 and H2, while catalyst alumina does so to produce carbon monoxide and H2O.

5. For reversible reaction, Equilibrium point remains unaffected but reached sooner: It is observed that in a reversible reaction, the catalyst accelerates the reverse reaction to the same extent as the forward reaction so that the ratio of their velocities i.e. the equilibrium constant remains the same. Examples: (a) Oxidation of sulphur dioxide: 2SO2 + O2 2SO3 The presence of platinized silica gel increases the rate of oxidation of SO2 but it will never contribute towards the yield of SO3 under the given conditions of temperature. (b)Formation of ammonia by Haber process: N2 + 3H2 2NH3 Here the catalyst only accelerates the speed of reaction, but equilibrium constant remains unchanged. (N.B.: This is true only if the catalyst is in small amount.) 6. Nature of catalytic surface: Activity of a catalyst depends on the nature of catalytic surface. F.C.Frank has proved that the crystal edge, corners, grain boundaries and number of other physical irregularities of surface provide active centers of unusual high catalytic activity. Examples: (a)In Ostwald s process, Pt-Rh gauze is used to catalyze the reaction between NH3 and O2 to manufacture nitric acid. (b) Pellets of V2O5 are used to oxidize SO2 to SO3 in manufacture of H2SO4 by contact process.

7. Surface activeness of the catalyst: If a catalyst is surface active, its effectiveness is generally increased by increasing its available surface area rather than merely increasing the mass of the catalyst. 8. Effect of temperature: Due to rise in temperature, the physical forms of some of the catalysts are altered and hence their catalytic power decreases. However, a catalyst does not make reaction more exothermic. Example: Platinum acting as a catalyst in the form of colloidal solution loses its activity on increasing temperature that causes its coagulation. Example: Platinum acting as a catalyst in the form of colloidal solution loses its activity on increasing temperature that causes its coagulation. Hence for every catalyst, there must be an optimum temperature at which the efficiency of the catalyst is maximum. Examples: (a)Manufacture of H2SO4 by contact process: Platinized asbestos is efficient at 400 450 C (673 723K). (b) Manufacture of HNO3 by Ostwald s process: Platinum gauze is efficient at about 800 C (1073 K). 9. Activation of catalysts (Promoter action): Efficiency of some of the solid catalysts is considerably enhanced by the presence of small amounts of other substances which themselves may not be catalytically active. Such substances which promote the activity of catalyst, to which they are added in small amounts, are called as Promoters or Activators and this process in known as Activation.

10. Catalytic poisoning: Any substance which reduces or completely destroys the activity of the catalyst is called a catalytic poison and the phenomenon is known as catalytic poisoning. Small traces of impurities in the reacting substances are found to retard and damage the contact catalysts. The catalytic poisoning may be temporary or permanent depending upon the nature of impurities. Catalytic poisoning is just reverse to activation of catalysts. Examples: (a) Contact process for H2SO4: Traces of arsenic present in SO2 renders the platinum catalytically inert or inactive. (b) Haber process for NH3: Carbon monoxide present in hydrogen gas poisons the catalyst. The most effective catalytic poisons are HCN, CO and As2O3. The poisons have residual free valencies because of which they block the active sites of the catalysts and render them inactive. See Fig. 5.4.

5.5 i. Intermediate compound formation theory. ii. Adsorption theory. The understanding of mechanism of catalytic reactions has improved greatly in recent years because of availability of isotopically labeled molecules, advanced spectroscopic and diffraction techniques and improved methods for determining reaction rates. Catalytic reactions are of such a wide variety that it is not possible to explain their mechanism by a single theory. Therefore, only the more important theories may be outlined to give a clue regarding the catalysis. (i) Intermediate compound formation theory: According to this theory, the main function of the catalyst is to bring about the desired reaction between the molecules which do not possess sufficient energy for chemical combination. This is achieved by following some low energy path essentially, by lowering the enthalpy of activation. (The enthalpy of activation is the energy necessary to transform the reactants into the activated complex). This operation is through to involve the formation of intermediate by developing very weak linkages between catalyst and the reactants to form activated complex having energy somewhat lower than that is required in absence of catalyst. These also have the effect of loosening up the bonds in the reacting molecules prior to reaction. In homogeneous solutions it is, therefore, presumed that the catalyst reacts with either or all of the reactants to form an intermediate compound having low energy. This compound being unstable suffers decomposition to regenerate the catalyst with simultaneous formation of the desired product, as shown in Fig. 5.5. This function of the catalyst can be explained in terms of the mountain pass analogy, as depicted in Fig. 5.6. Mechanism of Catalysis

Suppose X and Y are reactants and C is the catalyst. The reaction will proceed as follows: X + Y Slow(((,\s\do8((High Ea XY (I) (Reactants) This is uncatalysed reaction, activation energy is high and the reaction is very slow. When catalyst is used, the reaction will proceed as follows: (a) X + C Fast(((,\s\do15(Low E\s(',a [X C] Reactant (I) Catalyst [X---C] + Y Fast(((,\s\do15(Low E\s(',a X Y + C (II) Intermediate Reactant (II) Product (Regenerated catalyst) (Product) (I) (Intermediate compound)

Examples: (a) Catalytic action of nitric oxide in the manufacture of sulphuric acid by chamber process. (i) O2 + 2NO 2[NO2] Reactant(X) Catalyst (C) Intermediate compound (XC) (ii) [NO2] + SO2 SO3 + NO Intermediate Reactant(Y) Product Regenerated catalyst Compound (XC) (b) Conversion of alcohol to ether in the presence of sulphuric acid as a catalyst (Acid- Base catalysis). (i) C2H5OH + H2SO4 [C2H5HSO4] + H2O Reactant Catalyst Intermediate compound (X) (C) (XC) (ii) [C2H5HSO4] + C2H5OH (C2H5)2O + H2SO4 (XC) (Y) (XY) (C) (c) Friedel-Craft s reaction: Formation of benzophenone (C6H5COC6H5) from benzene and benzoyl chloride using anhydrous aluminum chloride as a catalyst. (i) C6H5COCl + AlCl3 [C6H5COCl AlCl3] (X) (C) (XC) C6H5COCl AlCl3 + C6H6 (C6H5)2CO + AlCl3 + HCl (XC) (Y) (XY) (C) catalyst(C) Intermediate Reactant Product Catalyst

(ii) Adsorption Theory: The Modern Theory of Contact Catalysis: This theory was first put forward by Faraday in 1833. It is applicable to heterogeneous catalysis only. This theory is regarded as an outcome of the complete fusion of the two effects, namely simple adsorption and intermediate compound formation. According to this theory, the action of catalyst postulates that: (a) The reactants are adsorbed on the surface of a solid catalyst either by physical adsorption (physisorption) or by chemisorptions [See Fig. 5.7 (b) and (c)] and their concentration goes on increasing thereby causes an increase in the rate of reaction in accordance to the Law of Mass Action. (b) Due to the free valencies on the surface of the catalyst, the molecules of reactants enter into a sort of loose chemical combination with the catalyst and hence with each other. [See Fig.5.7 (a) and (c)]. At this stage, the system is assumed to form an adsorbed activated complex that provides a new pathway to the reaction having lower enthalpy of activation (Ein Fig. 5.5).For example: The adsorbed activated complex being associated with higher amount of energy than those of reactants and products, it is under strain and is highly reactive. It is, therefore, readily desorted and decomposes to products leaving the surface free for next reactant molecules so that the process is continued

This mechanism may by depicted as follows: (a)Schematic view of mechanism of heterogeneous catalysis by surface adsorption Fig. 5.7 (a),) b), (c): Mechanism of heterogeneous catalysis

Adsorption theory and Characteristics of Catalysts: (a) Finely Divided Catalyst: The surface of metal possesses free valencies and thus acts as a seat of chemical force of attraction that holds up the reactant molecules by loose chemical combination. On breaking the metal into the powder, the numbers of free valencies are increased and thus the efficiency of the catalyst is increased. (See Fig .5.8). Fig. 5.8: Increase of Free Valencies on Breaking the Metal (b) Rough Surface (Active centers): The metals with rough surfaces have increased catalytic efficiency. This is attributed to the fact that at the rough surface such as peaks, cracks, corners, edges, bends, etc. (see Fig. 5.9), there are a large number of free valencies and therefore, they act as the active centers and bring about rapid conversion of reactants into products by comparatively lower energy requirement (E)for the formation of adsorbed activated complex. Fig. 5.9: Active centers on the metal surface

(c) centers are blocked. This leads to the decrease in rate and destruction of catalytic activity of the substance. This is nothing but catalytic poisoning. (d) Action of Promoters: At the interfaces of catalyst and promoters, there is probably overcrowding of free valencies. This phenomenon leads to increased adsorption of reactants (Law of Mass Action) that increases their concentration, and therefore, enhances the rate of catalysis. See Fig. 5.3. (e) Specificity of Catalysts: Due to free valencies on the surface, catalysts show a good chemical affinity towards specific reactants only that leads to their adsorption and the subsequent reaction. Thus the catalytic action is highly specific. 5.6 Industrial Applications of Catalysis: Catalysts are of immense and are widely used in the majority of the industrial processes. The new and better catalysts are always sought in industry. The reason for this is very simple. The more efficient the catalyst, the lower the temperature at which a reaction will proceed, and therefore the lesser the fuel consumption and more economical is industrial process. Action of Poisons: The impurities are adsorbed on the catalyst surface and the active

Some of the catalyzed industrial processes have been summarized in Table 3.1. Table 5.1: Catalysis and connected Industrial Processes Industrial process Catalyst Reaction Contact Process(H2SO4) 1. Platinum Metal 2. V2O5 2SO2 + O2 2SO3 673-723k, (1.5-1.7) 105pa Chamber Process (H2SO4) (NO + NO2) 2SO2 + O2 + 2H2O 2 H2SO4 Haber Process (NH3) Fe, [Al2O3, K2O] OR [Mo(promoter)] N2 + 3H2 2NH3 673-773K, 230 105 pa Ostwald s Process (HNO3) (Platinum + 5 to 7% Rhodium) Gauze 4NH3+502 4NO + 6H2O Ammonia : Air 1 : 10 Hydrogen (from CH4) Ni + MgO Ni + Al2O3 2CH4+02 2CO + 4H2

Hydrogen (from steam) Water gas reaction Sulphur (from coal gas) Calcium Cyanamide Oxygen from KClO3 Fe salt and Copper 3Fe + 4H2O Fe3O4 + 4H2 Ni and Co CO + H2O CO2 + H2 Nickel oxide Fe2O3+3H2S 2FeS + 3H2O + S Charcoal + Alkali CaC2 + N2 Ca(CN)2 + C MnO2 2KClO3 2KCl + 3O2 Methyl Alcohol (from CO + H2) Ether (from alcohol) Methane (from CO + H2) Friedel Crafts Reaction ZnO + Cr2O3 CO + 2H2 CH3OH H2SO4 Nickel Anhydrous AlCl3 2C2H5OH (C2H5)2O + H2O Co + 3H2 CH4 + H2O C6H5COCl + C6H6 (C6H5)2CO + HCl C2H5OH + CH3COOH CH3COOC2H5 + H20 C6H12O6 2C2H5OH + 2CO2 Esterification H2SO4 Ethyl Alcohol (from Glucose) Ammonia (from Urea) Glucose (from Maltose Methyl Alcohol (from Methane) Zymase Urease CO(NH2)2 + H2O 2NH3 + CO2 Maltase C12H22O11 + H2O 2C6H12O6 Copper 2CH4(g) + O2(g) 2CH30H(g)