Lower Respiratory Tract Infections and Their Management

Learn about lower respiratory tract infections such as laryngeal and tracheal infections, their symptoms, clinical evaluation, management, and the importance of recognizing signs of airway obstruction in young children. Discover the causes, epidemiology, and potential complications of viral croup, a common type of laryngotracheal infection in children aged 6 months to 6 years.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

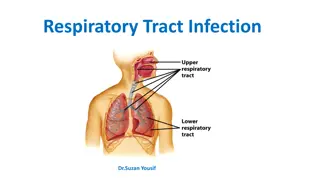

Lower Respiratory Lower Respiratory Tract Infection Tract Infection Dr Maria Darko

Laryngeal & Tracheal Laryngeal & Tracheal Infections Infections

Introduction Introduction The mucosal inflammation and swelling produced by laryngeal and tracheal infections can rapidly cause life-threatening obstruction of the airway in young children. They are characterised by : Stridor, a rasping sound heard predominantly on inspiration Hoarseness due to inflammation of the vocal cords Barking cough Variable degree of dyspnoea

Clinical Evaluation Clinical Evaluation The severity of airway obstruction is best assessed clinically by The degree of chest retraction Degree of stridor Severe obstruction leads to increasing respiratory rate, heart rate and agitation. Central cyanosis or drowsiness indicates severe hypoxaemia and the need for urgent intervention. The measurement of oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry is the most reliable objective measure of hypoxaemia.

Management Management Don't examine the throat ! Unless full resuscitation equipment and personnel are at hand Total obstruction of the upper airway may be precipitated by examination of the throat using a spatula. Observe carefully for signs of hypoxia or deterioration. Administer nebulised epinephrine. If respiratory failure develops from increasing airway obstruction, exhaustion or secretions blocking the airway, urgent tracheal intubation is required.

Chest Retraction Chest Retraction

Viral Croup Viral Croup

Aetiology Aetiology Viral croup accounts for over 95% of laryngotracheal infections. Parainfluenza viruses are the commonest cause. Other viruses, such as metapneumovirus, RSV and influenza, can produce a similar clinical picture. There is mucosal inflammation and increased secretions affecting the larynx, trachea and bronchi.

Epidemiology Epidemiology The oedema of the subglottic area is potentially dangerous in young children. This is because it may result in critical narrowing of the trachea. Croup occurs from 6 months to 6 years of age. The peak incidence is in the second year of life. Croup is commonest in the wet season.

Clinical Features Clinical Features The typical features are Barking cough Harsh stridor Hoarseness Usually preceded by fever and coryza. The symptoms often start, and are worse, at night.

Management Management The child with mild viral croup can usually be managed at home. When the airway obstruction is mild, the stridor and chest recession disappear when the child is at rest. The parents need to observe the child closely for the signs of increasing severity. The decision to manage the child at home or in hospital is influenced by The severity of the illness. The time of day. Ease of access to hospital. The child's age ( low threshold for admission for those <12 months old). Parental understanding and confidence about the disorder.

Management Management Inhalation of warm moist air is widely used but is of unproven benefit. Oral dexamethasone or prednisolone relieves inflammation. Nebulised steroids (budesonide) reduces the severity and duration of croup and the need for hospitalisation. Nebulised epinephrine provides transient improvement. Children with the clinical features of severe croup, or an oxygen saturation of less than 93% in air should be given nebulised epinephrine with oxygen by face mask and closely monitored. Few children with croup may require tracheal intubation.

Bacterial Tracheitis Bacterial Tracheitis

Bacterial tracheitis Bacterial tracheitis This rare but dangerous condition is usually caused by infection with Staphylococcus aureus or H. influenzae. The clinical picture is similar to severe viral croup The exception is that the child Has high fever Appears toxic and Has rapidly progressive airway obstruction with copious thick airway secretions. Treatment is intravenous antibiotics, intubation and ventilation if required.

Acute Epiglottitis Acute Epiglottitis

Introduction Introduction Acute epiglottitis is a life-threatening emergency due to respiratory obstruction. It is caused by H. influenzae type b. The introduction of universal Hib immunisation in infancy has led to a decrease of over 99% in the incidence of epiglottitis and other invasive H. influenzae type b infections. There is intense swelling of the epiglottis and surrounding tissues associated with septicaemia.

Epidemiology Epidemiology Epiglottitis is most common in children aged 1-6 years but affects all age groups. It is important to distinguish between epiglottitis and croup as they require different treatment. The onset of epiglottitis is often very acute with: High fever in an ill, toxic-looking child. An intensely painful throat

Clinical Features Clinical Features This prevents the child from speaking or swallowing. Saliva drools down the chin. Soft inspiratory stridor. Rapidly increasing respiratory difficulty over hours The child sits immobile, upright, with an open mouth to optimise the airway.

Epiglottitis Epiglottitis Child sitting immobile, upright With an open mouth to optimise the airway.

Evaluation Evaluation In contrast to viral croup, cough is minimal or absent. Attempts to lie the child down or examine the throat with a spatula must not be undertaken as they can precipitate total airway obstruction and death. If the diagnosis of epiglottitis is suspected, urgent hospital admission and treatment are required. A senior anaesthetist, paediatrician and an ENT surgeon should be summoned and treatment initiated without delay. The child should be transferred directly to the intensive care unit, and must be accompanied by senior medical staff in case respiratory obstruction occurs.

Management Management The child should be intubated Sometimes this is impossible and urgent tracheostomy is life-saving. After the airway is secured blood should be taken for culture and intravenous antibiotics such as cefuroxime started. The tracheal tube can usually be removed after 24 hours and antibiotics given for 3-5 days. With appropriate treatment, most children recover completely within 2-3 days.

Bronchitis Bronchitis

Overview Overview Cough and fever are the main symptoms. The cough may persist for about 2 weeks, or longer with pertussis or Mycoplasma infections. There is no evidence that antibiotics, cough suppressants or expectorants speed recovery. Treatment is supportive

Whooping Cough Whooping Cough

Epidemiology Epidemiology This is a highly infectious form of bronchitis It is caused by Bordetella pertussis. It is endemic, with epidemics every 3-4 years. After a week of coryza (catarrhal phase), the child develops a characteristic paroxysmal or spasmodic cough followed by a characteristic inspiratory whoop (paroxysmal phase). The spasms of cough are often worse at night and may end up in vomiting. During a paroxysm, the child goes red or blue in the face, and mucus flows from the nose and mouth.

Clinical Features Clinical Features The whoop may be absent in infants Apnoea is a feature in infants Epistaxis and sub conjunctival haemorrhages can occur after vigorous coughing. The paroxysmal phase lasts 3-6 weeks. The symptoms gradually decrease during the convalescent phase but may persist for many months.

Complications Complications Complications of pertussis, are Pneumonia Convulsions and Bronchiectasis These complications are quite uncommon. There is still a significant mortality, particularly in infants who develop apnoea. Infants and young children suffering severe spasms of cough or cyanotic attacks should be admitted to hospital.

Management Management The organism can be identified early in the disease from culture of a peri-nasal swab. Characteristically, there is a marked lymphocytosis (>15 109/L). Erythromycin eradicates the organism. It decreases symptoms only if started during the catarrhal phase. Siblings, parents and school contacts may develop a similar cough.

Prevention Prevention Close contacts should receive erythromycin prophylaxis. Unvaccinated infant contacts should be vaccinated. Immunisation reduces the risk of developing pertussis and the severity of disease in those affected, but does not guarantee protection. The level of protection declines steadily during childhood.

Bronchiolitis Bronchiolitis

Epidemiology Epidemiology Bronchiolitis is the commonest serious respiratory infection of infancy: 2-3% of all infants are admitted to hospital with the disease each year during annual winter epidemics or rainy season. 90% are aged 1-9 months (bronchiolitis is rare after 1 year of age). Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the pathogen in 80% of cases. Human metapneumovirus is a recently identified virus causative organism. Other respiratory viruses accounts for the rest of cases.

Clinical Features Clinical Features Coryzal symptoms precede a dry cough and increasing breathlessness. Wheezing is often, but not always, present. Feeding difficulty associated with increasing dyspnoea is often the reason for admission to hospital. Recurrent apnoea is a serious complication, especially in young infants. Infants born prematurely who develop broncho pulmonary dysplasia and infants with congenital heart disease are most at risk .

Clinical Features Clinical Features The characteristic findings on examination are : Sharp, dry cough Tachypnoea Subcostal and intercostal recession Hyperinflation of the chest Prominent Sternum Liver displaced downwards Fine crackles heard at the end of inspiration High-pitched wheezes - expiratory > inspiratory. Tachycardia Cyanosis or pallor.

Clinical Findings in Bronchiolitis Clinical Findings in Bronchiolitis

Investigations Investigations RSV can be identified rapidly on nasopharyngeal secretions. A chest X-ray shows hyperinflation of the lungs due to small airways obstruction, air trapping and often focal lung collapse. Blood gas analysis, which is required in only the most severe cases, shows lowered arterial oxygen and raised CO2tension.

X X- -ray Findings in Bronchiolitis ray Findings in Bronchiolitis Hyper inflated Chest Normally Inflated Lungs

Management Management Supportive. Humidified oxygen is delivered via nasal cannulae or into a headbox. The concentration of oxygen required is determined by pulse oximetry. The infant is monitored for apnoea. Mist, antibiotics and steroids are not helpful.

Management Management Nebulised bronchodilators, such as salbutamol or ipratropium, though often used, have not been shown to reduce the severity or duration of the illness. Fluids may need to be given by nasogastric tube or intravenously. Mechanical ventilation is required in about 2% of infants admitted to hospital. RSV is highly infectious. Infection control measures, particularly good hand hygiene, are needed to prevent cross-infection to other infants in hospital.

Prognosis Prognosis Most infants recover from the acute infection within 2 weeks. However, as many as half will have recurrent episodes of cough and wheeze . Rarely, usually following adenovirus infection, the illness may result in permanent damage to the airways (bronchiolitis obliterans).

Prevention Prevention A monoclonal antibody to RSV - palivizumab can be given monthly. It is given by intramuscular injection. This reduces the number of hospital admissions in high-risk preterm infants. Its use is limited by cost and the need for several injections

Thank you Thank you Questions? Comments? Contributions?