Novel Approach to Camera Frequency Detection

Explore a unique concept for detecting frequencies using camera exposure times in Visible Light Communication systems. Learn about the limitations and solutions proposed by Stan Baggen in this insightful study.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

On a Generalization of the GCD for Intervals in R+ or how can a camera see at least 1 tone for unkown Texp Stan Baggen June 4, 2014

Contents Introduction Cameras, exposure times and problem definition Introduction to Solution using GCD for Integer Frequencies Extension of GCD to intervals over R+ Application to the Original Problem Discussion Yet another generalization Philips Research 2 Stan Baggen

Introduction Transmit digital information from a luminaire to a smartphone or tablet using Visible Light Communication (VLC) Bits are encoded in small intensity variations of the emitted light Detect bits using the camera of a smartphone We consider an FSK-based system Symbols correspond to frequencies (tones) Emitted light variations are sinusoidal Problem: camera may be blind for certain frequencies Philips Research 3 Stan Baggen

Camera Image divided into lines and pixels original image sequence lines covering source active lines lines per frame hidden lines Each line consists of a row of pixels Philips Research 4 Stan Baggen

Exposure Time A camera can set its exposure time Texp typically, Texp ranges from 1/30 to 1/2500 [s] Each pixel sees the average light during Texp seconds before read-out smearing of intensity variations of received light If an integer number of periods of a sinusoid fit into Texp, the camera cannot detect such a sinusoid Transfer Function of Exposure Time 1 |sinc(f)| |sinc(0.7f)| 0.9 0.8 ISI filter (moving average) 0.7 0.6 Texp |sinc(f)| 0.5 0.4 f1 f2 time 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 f 6 7 8 9 10 Philips Research Stan Baggen

Exposure Time Due to the exposure time Texp of a camera, certain frequencies cannot be detected by it (multiples of fexp = 1/Texp) Can we have sets of 2 frequencies each, such that not both can be blocked for any fexp 30 Hz Each set then forms an fexp-independent detection set for a light source that emits both frequencies Transfer Function of Exposure Time 1 |sinc(f)| |sinc(0.7f)| 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 |sinc(f)| ISI filter 0.5 Texp 0.4 f1 f2 0.3 0.2 time 0.1 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 f 6 7 8 9 10 Philips Research 6 Stan Baggen

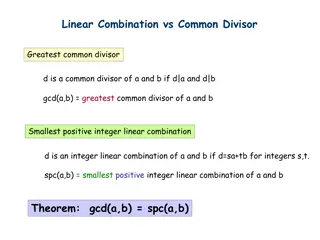

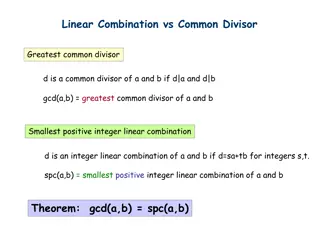

Discrete Solution If the involved frequencies can only take on integer values, we can find solutions using the GCD (Greatest Common Divisor) from number theory We would like to have 2 frequencies f1 and f2, such that not both can be integer multiples of any fexp 30 Suppose that both f1 and f2 are integer multiples of fexp | f f exp 1 | GCD( , ) f f f exp 1 2 | f f exp 2 If GCD(f1,f2) < 30 no solution possible for fexp 30 pair (f1,f2) is a good choice Philips Research 7 Stan Baggen

Discrete Solution: Example f1 = 290; f2 = 319 Largest integer that divides both f1 and f2 equals GCD(f1,f2) = 29 No integer fexp 30 exists for which multiples are simultaneously equal to f1 andf2 Philips Research 8 Stan Baggen

Problem with Discrete Solution GCD(300,301) = 1; GCD(300,300) = 300 Physically: due to the nature of the Texp-filter and detection algorithms, if a pair of frequencies (f1,f2) is bad for detection, then a real interval (f1 ,f2 ) is also bad Transfer Function of Exposure Time 1 |sinc(f)| |sinc(0.7f)| 0.9 We need a method that allows us to eliminate bad intervals over R+ 0.8 0.7 0.6 |sinc(f)| 0.5 0.4 f1 f2 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 f 6 7 8 9 10 Philips Research 9 Stan Baggen

GCD for intervals in R+ Consider 2 half-open intervals I1 and I2 in R+ I1 I2 ( ] ( ] 0 ( ) Definition: = GCD( , : ) max | I I a R na I ma I 1 2 , 1 2 n m N Note that the concept I1,I2:GCD(I1,I2) < 30 solves our original problem: 1 F 2 F ( ] ( ] 30 0 There can be no real fexp 30 such that integer multiples are simultaneously close to F1 and F2 Philips Research 10 Stan Baggen

GCD for intervals in R+ I1 I2 ( ] ( ] 0 ( ) = GCD( , : ) max | I I a R na I ma I 1 2 , 1 2 n m N How to find GCD(I1,I2)? ( ) ) = | D d R nd I Define divisor sets D1,D2 in R: 1 1 I n N ( = | D d R md 2 2 m N Theorem 1: = GCD( , ) max I I D D 1 2 1 2 ( nd ) ( ) Proof: = | | D D d R nd I d R md I 1 2 1 2 n N m N ( ) ( ) N = | d R I md I 1 2 n m N Philips Research 11 Stan Baggen

Example divisor sets, their intersection and the GCD, f1 = 240, f2 = 256, interval = 16 5 f1 = 240 f2 = 256 GCD = 28.4444 4 3 ( ) = = | ( 240 16 , 240 ] D d R nd I I 1 1 1 n N 2 ( ) = = | ( 256 16 , 256 ] D d R md I I 2 2 2 m N 1 D D 1 2 0 GCD( , ) I 1I 2 -1 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 frequency Philips Research 12 Stan Baggen

Enlargement of Example divisor sets, their intersection and the GCD, f1 = 240, f2 = 256, interval = 16 f1 = 240 f2 = 256 GCD = 28.4444 2.5 D 1 2 1.5 D 2 1 0.5 GCD( , ) I 1I 2 D D 1 2 0 10 15 20 25 30 frequency Philips Research 13 Stan Baggen

Overlap of Intervals in Divisor Sets ( ) Consider divisor set = = | , ( , ] D d R nd I I f w f n N f w f I = = 3 2 n n ( ] D D = 3 1 0 D = 2 1 1 / 3 D / 2 D Let where n = = D = Dn n | / , d R nd I I n n N D Theorem 2: for w>0, D consists of a finite number n0 of disjunct intervals, where w f = n0 Proof: overlap of consecutive intervals happens if f f w 1 f f = . n n 0 n n w w f f ( , 0 Corollary: , 0 , , 0 D w n n 0 0 Philips Research 14 Stan Baggen

Another Theorem Suppose that we have 2 intervals I1=(f1-w1,f1] and I2=(f2-w2,f2] Theorem 3: For w1,w2> 0, GCD(f1,f2 ; w1,w2) equals an integer sub-multiple of either f1, f2 or both Proof: = = i j i j i i , D D D D D D 1 2 1 2 1 2 j j equals a right limit point of for some i and j. 2 1 max D D i j D D 1 2 Each is the intersection of 2 half-open intervals (...], where the right limit point of each half-open interval is an integer sub-multiple of either f1 or f2 or both. Note: f1 and f2 are real numbers i j D D 1 2 Philips Research 15 Stan Baggen

Some Interesting Examples Numbers in N+ For w sufficiently small, we find the classical solutions for f1, f2 in N+ GCD(15,21; w 1) = 3 GCD(15,21; w=1.1) = 7 w too large for finding the classical solution Numbers in Q+ GCD(0.9,1.2; w=0.1) = 0.3 Numbers in R+ (computed with finite precision) GCD(7 ,8 ; w=0.1) = 3.1416 GCD(6 ,8 ; w=0.1) = 6.2832 Philips Research 16 Stan Baggen

Application to the Original Problem Suppose that we find that for a certain (f1, f2; w1,w2) : GCD (f1, f2; w1,w2) < 30 1 F 2 F f f 2f w w 1f 2 2 ( ] 1 1 ( ] 30 0 f Then there exists no real number fexp 30 such that integer multiples of fexp fall simultaneously in (f1-w1, f1] and (f2-w2, f2] By picking F1= f1-w1/2 and F2= f2-w2/2, we can insure that if one multiple of fexp 30 falls within a range of wi/2 of Fi for some i, then the other interval is free from any multiple of fexp Philips Research 17 Stan Baggen

Numerical Examples (1) Acceptable integer frequency pairs for w = 15, GCD < 30, 100 < f < 700 1200 1000 acceptable frequency pairs 800 600 400 200 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 frequency acceptable_frequencies_2012_10_20_1 Philips Research 18 Stan Baggen

Numerical Examples (1) detail Acceptable integer frequency pairs for w = 15, GCD < 30, 100 < f < 700 300 acceptable frequency pairs 250 200 150 100 100 120 140 160 frequency 180 200 220 typical solutions: (f1,f2) = (f1, f1+15) acceptable_frequencies_2012_10_20_1 Philips Research 19 Stan Baggen

Numerical Examples (2) Acceptable integer frequency pairs for w = 14, GCD < 30, 100 < f < 700 2500 2000 acceptable frequency pairs 1500 1000 500 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 frequency acceptable_frequencies_2012_10_18_2 Philips Research 20 Stan Baggen

Numerical Examples (2) detail Acceptable integer frequency pairs for w = 14, GCD < 30, 100 < f < 700 350 300 acceptable frequency pairs 250 200 150 100 50 0 90 100 110 120 130 140 150 160 170 180 190 frequency acceptable_frequencies_2012_10_18_2 Philips Research 21 Stan Baggen

Numerical Examples (3) Acceptable integer frequency pairs for w = 12, GCD < 30, 100 < f < 700 5000 4500 4000 3500 acceptable frequency pairs 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 frequency acceptable_frequencies_2012_10_18_3 Philips Research 22 Stan Baggen

Numerical Examples (4) Acceptable integer frequency pairs for w = 10, GCD < 30, 100 < f < 700 9000 8000 7000 acceptable frequency pairs 6000 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 frequency acceptable_frequencies_2012_10_18_4 Philips Research 23 Stan Baggen

Numerical Examples (4) detail Acceptable integer frequency pairs for w = 10, GCD < 30, 100 < f < 700 900 800 700 acceptable frequency pairs 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 100 120 140 160 180 200 220 240 260 280 300 frequency typical solutions: (f1,f2) = (f1, f1+15), (f1, 2f1-20), ), (f1, 2f1+15) acceptable_frequencies_2012_10_18_4 Philips Research 24 Stan Baggen

Discussion (1) It is convenient to use half open intervals ( ] and have the right limit point as a characterizing number, since then We can reproduce the familiar results from number theory The maximum in the definition of GCD exists We do not obtain subsets in having measure 0 D D 1 2 The concept of GCD can be generalized to an arbitrary number of K intervals over R+ I I 1 ) ,..., GCD( = K k = max D K k 1 Theorem 2 shows that the complexity of the computation of a GCD is reasonable Can we have an efficient algorithm like Euclid s algorithm for computing the GCD of real intervals? Philips Research 25 Stan Baggen

Discussion (2) It can be shown that GCD(f1, f2;w) is non-decreasing as w increases For rational numbers a/b and p/q, where a,b,p,q are in N+, we find for sufficiently small w: = a p LCM( , ) , LCM( , ) GCD b q b q b q a p , ; , GCD w LCM( , ) b q b q where LCM(.) is the Least Common Multiple. How small must w be as a function of a,b,p and q to find this solution? ( ) Conjecture: for incommensurable numbers a and b = lim w , ; 0 GCD a b w 0 Effects of finite precision computations Philips Research 26 Stan Baggen

Yet Another Generalization GCD(f1,f2;w) on intervals still makes hard decisions on frequencies being in or out of intervals Can we make some sensible reasoning that leads to smooth decisions concerning acceptable frequency pairs We have to use a more friendly measure on the intervals We start by re-phrasing the previous approach in a different manner Philips Research 27 Stan Baggen

GCD(f1,f2;w) on intervals as discussed previously, effectively uses indicator functions as a measure of membership: M M 1I 2 I 1 ( ] I1 ( ] I2 f 0 + = = ( ) 1 ; ( ) 1 , M f M f f R I I I I 1 1 2 2 Divisor Measure DM1,DM2 in R+ + = 2 , 1 = ( : ) max n ( ), , DM f M nf f R i i iI N 1 = = ( , : ) 2 max f ( ) ( ) GCD I I DM f DM f 1 1 2 + R Philips Research 28 Stan Baggen

Cost Functions 7 D1 D2 D1 D2 Example 6 9 5 4 costs 12 f1 = 9; f2 = 12 3 2 w = 0.5 3 1 GCD(f1,f1;w) = 3 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 f Cost Functions D1 D2 D1 D2 6 5 4 costs 3 2 1 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 Philips Research 29 Stan Baggen f

Using a Different Measure Suppose that we change the definition of the measure of membership for the fundamental interval ( ) 2 f f + = 2 , 1 = ( ; , : ) i exp , , i M f f f R i i 2 i 2 example Divisor Measure: Cost Functions of Fundamental Intervals I1 and I2 3 + = 2 , 1 = ( ; , : ) i max n ( ; , ), , DM f f M nf f f R i 2.5 ( f ; 12 . 0 , 25 ) M i i i N 2 Common Divisor Measure: costs 1.5 1 = ( ; , , , : ) 2 ( ; , ) ( ; , ) CDM f f f DM f f DM f f 1 2 1 1 1 2 2 0.5 ( f , 9 ; . 0 25 ) M 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 f Philips Research 30 Stan Baggen

Cost Functions 7 D1 D2 D1 D2 Example 6 5 ( f , 9 ; . 0 25 ) DM 4 costs 3 ( f ; 12 . 0 , 25 ) DM 2 1 ( f , 9 ; 12 . 0 , 25 . 0 , 25 ) CDM 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 f Cost Functions 1.4 D1 D2 D1 D2 Multiples of frequencies in the neighborhood of 3 (and 3/n) also end up both near 9 and 12 ( f , 9 ; 12 . 0 , 25 . 0 , 25 ) CDM 1.2 1 For frequencies f>3.2, no multiples end up both near 9 and 12 according to the measure 0.8 costs 0.6 0.4 Multiples of 1.1, 1.3 and 1.7 come somewhat close to both 9 and 12 (c.f. other measure) 0.2 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 Philips Research 31 Stan Baggen f

Cost Functions 7 D1 D2 D1 D2 Example 6 5 ( f , 9 ; ) 5 . 0 DM 4 costs 3 ( f ; ) 5 . 0 , 12 DM 2 1 ( f , 9 ; 12 , 5 . 0 , ) 5 . 0 CDM 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 f Cost Functions D1 D2 D1 D2 1.2 If we increase , it becomes more difficult to avoid the intervals around 9 and 12 for integer multiples of f 1 0.8 costs 0.6 For =0.5, some multiples of 4.16 also come close to both 9 and 12 according to the measure 0.4 0.2 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 4 4.5 Philips Research 32 Stan Baggen f

Cost Functions of Fundamental Intervals I1 and I2 3 Example ( f ; ) 5 . 0 , 12 M 2.5 f1 = 9; f2 = 12 = 0.5 fexp = 4.16 2 costs 1.5 1 0.5 ( f , 9 ; ) 5 . 0 M 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 f samples taken at integer multiples of 4.16 CDM(4.16;.) equals product of largest red sample (n=3) and largest blue sample (n=2) Philips Research 33 Stan Baggen

Philips Research 34 Stan Baggen